Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 20:03 — 19.8MB)

Subscribe: | More

It’s our one-year anniversary! To celebrate, I’ve opened up a Patreon bonus episode for anyone to listen to. Just click the link below and you can listen in your browser:

bonus episode – Salty Animals

This week’s episode is about dragons, specifically dragons of western/English-speaking tradition. Even narrowing it down like that leaves us with a lot of ground to cover! Thanks to Emily whose suggestion of the Komodo dragon as a topic started this whole ball rolling.

A dragon from the game Flight Rising, specifically one of MY dragons. Her name is Lily. She’s so pretty.

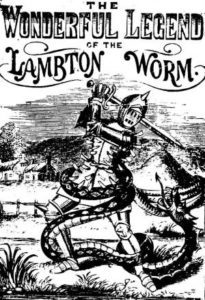

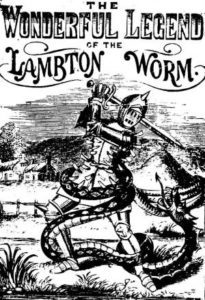

The Lambton worm:

A spitting cobra:

A Nile crocodile:

Deinosuchus skeleton and two humans for scale. I stole this off the internet as usual so I don’t know who the people are. They look pretty happy to be in the picture:

St. George and the Dragon (REENACTMENT):

Klagenfurt dragon statue:

A wooly rhino skull:

The star of the show today, the Komodo dragon!

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week let’s celebrate the podcast’s one-year anniversary with a big episode about dragons. Emily suggested komodo dragons as a topic, and then it all just spiraled out of control from there.

But first, a bit of housekeeping. Since it’s our one-year anniversary I’ve unlocked a Patreon episode so that anyone can listen. This one’s about salty animals. There’s a link in the show notes. Just click it and it’ll take you to the page where you can listen on your browser. You don’t need a Patreon login or anything.

Second, I got a polite correction recently from a listener about subspecies. Podbean is being a butt so I can’t actually see the comment, just read it in the email they sent, so I’m not sure who to thank. But they pointed out that “when the subspecies name is the same as the species name, it means it’s the first subspecies formally described, or the nominate subspecies.” In other words, Panthera tigris tigris didn’t get that second tigris because it’s extra tigery, it got it because it was the first tiger subspecies described. Although it is extra tigery.

So now, let’s learn about dragons.

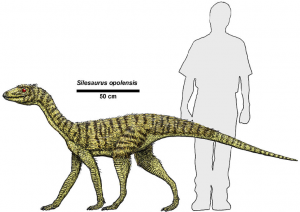

Until the early 13th century or so, the word dragon wasn’t part of the English language. We swiped it from French, which in turn got it from Latin, which took it from Greek. Before the word dragon became a common word, dragon-like creatures were frequently called worms. A worm used to mean any animal that was snakey in shape. Old stories of dragons in English folklore are frequently snakier than modern dragons. For instance, the Lambton worm.

The story goes that a man called John Lambton went fishing one Easter Sunday instead of going to church, and as punishment he caught not fish but a black leech-like creature with nine holes on each side of its head. He flung it into a well in disgust, and joined the crusades to atone for fishing on the Sabbath. But while he was gone, the worm grew enormous. It killed people and livestock, uprooted trees, and even blighted crops with its poisonous breath. It couldn’t be killed, either, because if it was chopped in two, its pieces rejoined.

When John Lambton returned from the crusades seven years later and found out what had happened, he sought the advice of a local wise woman about what to do. Then he covered a suit of armor with sharp spines, and wearing it, lured the worm into the river Wear, where it tried to squeeze him to death. But the spines cut it up into pieces that were swept away by the river so they couldn’t rejoin. The end.

I don’t want to derail the dragon talk too much here, but I’m just going to point out that the sea lamprey has seven little holes behind each eye called branchial openings. It’s also eel-like and can be partially black, and it’s gross. If you want to learn more about it, and about my irrational dislike of this interesting animal, you can go back and listen to episode three.

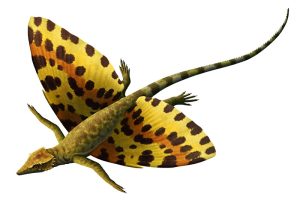

Anyway, even after English adopted the word dragon, it didn’t mean dragon exactly. It was just a word for a big snake, especially one with mythical attributes or enormous size. But artists the world over are fond of adding wings and legs to reptiles, especially to snakes. Snakes just look so…undecorated. Gradually dragon took on its current meaning, that of a reptile with four legs, possibly a pair of wings, decorative horns and spikes and spines, and the ability to breathe fire. Actual. Fire.

That kind of dragon simply can’t exist except in folklore and fiction. But human creativity aside, many aspects of the dragon, at least the dragons of western tradition, are based on those of real-life animals.

If you’ve listened to episode 12, about the wyvern, the basilisk, and the cockatrice, you may remember the confusion among those terms and what they stand for. Technically all three are types of dragons, since the definition of dragon is actually pretty loose. In that episode, we discussed the king cobra as the possible source of many stories of the basilisk.

The king cobra doesn’t spit venom, but many species of cobra do. While cobra venom won’t hurt you very much if it just touches undamaged skin, it will hurt your eyes if it gets into them. And spitting cobras aim for the eyes. The venom is actually sprayed directly from the cobra’s fangs, which have tiny holes in the front that work sort of like a spray bottle. Some species of cobra can spit venom over six feet, or two meters, and they can also inject venom by biting. Cobra venom can cause blindness if enough gets in the eyes, and it certainly causes eye pain and swelling. Not only that, but a few other species of venomous snake, such as the Mangshan pit viper, sometimes also spit venom.

As far as I’m concerned, a big snake that sprays venom at your eyes is a good basis for the story of a dragon that breathes fire. I’d almost rather deal with a firebreather, to be honest, because I know to stop, drop, and roll if I catch on fire. Be safe, kids. This has been a public service announcement.

Crocodiles have undoubtedly influenced dragon mythology. In fact, so many common dragon traits are present in crocodiles that if you discount the wings and firebreathing, crocodiles basically are dragons. The biggest crocodile living today is the saltwater crocodile, which can grow over 20 feet long, or 6 meters, and which lives in southeast Asia, eastern India, and northern Australia. The second biggest crocodile is the Nile crocodile, which can grow nearly as long, and which lives throughout much of Africa around rivers, lakes, and swamps. Male saltwater crocodiles are typically larger than females, while female Nile crocodiles are typically larger than males.

While crocodiles look like big lizards, they’re actually more closely related to birds and dinosaurs. They can also live a long time, occasionally over a hundred years. All crocodiles are good swimmers with webbed feet that help them change directions quickly. They can also run pretty fast out of water. A crocodile’s back is heavily armored with thick scales and osteoderms, or scutes, which are bony deposits in the skin. Crocodiles have long jaws studded with 80 teeth, and if a croc loses a tooth, another grows in its place. It can just keep replacing its teeth up to 50 times. It has good night vision, a good sense of smell, good hearing, and special sensory pits on its jaws that allow a croc to hunt and escape danger even in complete darkness. A croc’s stomach contains acid that would make even the bearded vulture envious, so it has no problem digesting bones, hooves, and horns efficiently, a good thing since Crocodiles usually swallow their prey whole. And crocodiles have the strongest bite of any living animal, stronger even than a great white shark.

Of course, there used to be bigger crocodiles. Do you want to learn about gigantic extinct crocodiles? OF COURSE YOU DO, that is basically why we’re all here.

Okay, so, there used to be a 35-foot, or almost 11-meter-long crocodile called Deinosuchus that lived around 75 million years ago in what is now North America. It basically looked like a modern crocodile, but its rear teeth were shorter and blunter than its front teeth. They were adapted to crush its prey rather than bite through it, probably because with a bite force that was probably stronger than a T. rex’s, it didn’t want to accidentally bite a big chunk out of the dinosaurs it ate. Yeah. It ate dinosaurs.

So crocodiles probably did a lot to inspire dragon folklore. There’s still a lot of mythology wrapped around the crocodile today, for that matter. You know those little birds that are supposed to clean crocodile teeth? Not actually a thing. I’ve lived my whole life thinking that was pretty neat, only to find it’s a myth.

Sometimes in spring a croc will lie in the water with sticks on its snout. When a bird flies down to pick up a stick for nesting, the crocodile will grab the bird and eat it. This is a real thing that happens, not a myth. Crocodiles are actually pretty smart. And sometimes they hunt in packs.

One of the most famous traditional dragon stories in the English language is that of St. George and the Dragon, which probably originated from stories brought back to Britain during the Crusades. The story became especially popular in the 13th century and there are many versions.

According to the story, a venomous dragon lived in a pond near a city, and had poisoned not only its pond, but the entire countryside. To keep the dragon from approaching the city, the people had to feed it their own children. Each day the people held a terrible lottery to see who had to send one of their children to the pond for the dragon to eat. One day the princess was chosen, and despite all the king’s gold and silver he had to send his daughter to be eaten by the dragon.

Fortunately for her, St. George just happened to be riding by. The dragon emerged from its pond and St. George thought, oh no, we’re not having any of that, and charged it. He wounded it with his lance, then had the princess give him her girdle to use as a collar. A girdle in this case was something between a decorative belt and a ribbon tied around the waist. As soon as St. George tied the girdle around the dragon’s neck, it became meek as a puppy and followed him back to the city.

Naturally, everyone was terrified, but St. George said he would kill the dragon if the king and his people would convert to Christianity. They did, he did, and that was the end of the dragon.

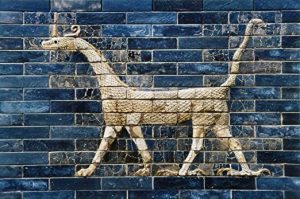

While crocodiles and big snakes undoubtedly strongly influenced dragon lore, something else did too. There’s a reason dragons are so often supposed to live in caves, for instance. Caves are good places to find fossils of huge extinct animals.

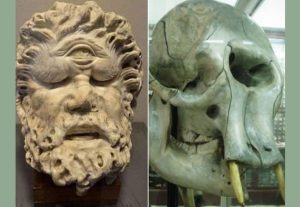

In Klagenfurt in Austria there’s a monument of a dragon, called the lindorm or lindwurm, that was erected in 1593. It still stands today, together with a statue of Hercules that was added almost 40 years later. The dragon statue is based on a story of the region. The story goes that a dragon lived near the lake and on foggy days would leap out of the fog and attack people. Sometimes people could hear its roaring over the noise of the river. Finally the duke had a tower built and filled it with brave knights. They fastened a barbed chain to a collar on a bull, and when the dragon came and swallowed the bull, the chain caught in its throat and tethered it to the tower. The knights came out and killed the dragon.

The original story probably dates to around the 12th century, but it was given new life in 1335 when a skull was found in a local gravel pit. It was clearly a dragon skull and in fact it’s still on display in a local museum. The monument’s artist based the shape of the dragon’s head on the skull. In 1935 the skull was identified as that of a wooly rhinoceros.

Other dragon stories probably started when someone saw huge fossils they couldn’t identify. Dragons, after all, can look like just about anything. Stories of benevolent dragons living on Mount Pilatus in Switzerland may have started by pterodactyl fossils that are frequently found in the area. In 1421 a farmer saw a dragon flying to the mountain, and it was so close to him that the farmer fainted. When he woke, he found a stone left for him by the dragon, which had healing properties. The dragonstone is in a local museum these days and has been identified as a meteorite.

It occurs to me that if one were rich, and by one I mean me, one could take a dragon tour through Europe and visit all these awesome monuments and museums. That would be part of my expedition to search for the tatzelwurm in the Alps.

We’ll finish up at the animal I mentioned at the beginning of the episode, the Komodo dragon. While in many respects the Komodo dragon is a real-life dragon, it probably didn’t influence traditional dragon stories in the western world because no one in Europe knew anything about it until 1910. It only lives on five small islands, notably Komodo, but it’s also found on the island of Flores where the Homo floresiensis remains were found.

There were rumors for years of a type of land crocodile found on Komodo. Dutch sailors said it actually breathed fire and could even fly. In 1910, a Dutch Colonial Administration official from Flores took some soldiers to Komodo and searched for the dragon. They shot one, and Peter Ouwens, director of the Zoological Museum in Bogor, Java, hired hunters who killed two more. Ouwens studied the lizards and published a formal description in 1912. In direct contrast to many governments of the time, who were apparently trying to drive as many species to extinction as possible, in 1915 the Dutch government listed the Komodo dragon as protected.

Keep in mind that at this time, people were completely bonkers about dinosaurs and other megafauna. The Komodo dragon got incredibly famous in a very short amount of time. A 1926 scientific expedition that brought back two live dragons and twelve preserved ones actually inspired the 1933 movie King Kong. Since Komodo dragons displayed in zoos proved to be huge draws, but didn’t survive long in captivity back then, if the dragon hadn’t already been protected it probably would have been driven to extinction by collectors capturing them for zoos and killing them to sell to museums as taxidermied specimens.

Researchers used to think that the Komodo dragon, which is a type of monitor lizard, demonstrated island gigantism, where some species that are typically not so big grow larger when a population is restricted to an island. Island dwarfism is its opposite, where big animals like elephants evolve to become smaller in an island habitat. But many species of monitor lizard are large even though they don’t live on islands, and it turns out that a close relative of the Komodo dragon lived in Australia until around 50,000 years ago. In fact, the first aboriginal settlers of Australia might have encountered it.

It was called Megalania and it was the largest straight-up lizard, as opposed to dinosaur, that’s ever been found. While we don’t have any complete skeletons, some researchers estimate it grew to around 18 feet long, or 5.5 meters, although older estimates had it up to 23 feet long, or 7 meters. Either way, it was much bigger than the Komodo dragon, which can grow just over ten feet long, or more than 3 meters.

Like the crocodile, the Komodo dragon’s skin contains osteoderms. It almost looks like it’s covered with tiny spines up close. Also like the crocodile, it grows new teeth when it loses old ones, which frankly is something I wish mammals could do because how useful would that be? It can run faster than a crocodile, can swim and dive well when it needs to although it prefers to stay on land, and when it’s young it can climb trees. Older dragons are too heavy to climb trees, but an adult can stand on its hind legs using its tail as a prop. It likes to dig burrows to sleep in, and females may dig nesting burrows 30 feet long, or 9 meters.

The Komodo dragon eats anything, from carrion to baby Komodo dragons to humans, but it especially likes deer and wild pigs. Its sense of smell is so acute, it can smell a dying animal almost six miles away, or 9 ½ km. It will swallow smaller prey whole but will tear chunks off of bigger carcasses.

We’re still learning about the Komodo dragon. For a long time researchers thought it had a nasty dirty mouth full of rotten meat, which infected its prey with bacteria when bitten. But it turns out that the Komodo dragon is actually venomous. This is still somewhat controversial, since the Komodo dragon’s saliva does contain 57 strains of bacteria and some researchers think that’s more toxic than its venom. Whatever the case, you do not want to be bitten by a Komodo dragon.

It’s primarily an ambush predator, and when it attacks an animal, it gives it a bite with its huge serrated teeth. If the animal gets away, no problem. The dragon’s venom contains anticoagulants so it will probably die of blood loss. As for the dragon itself, its blood actually contains antimicrobial proteins. Researchers hope to develop new antibiotics from the proteins.

Komodo dragon eggs are big, about the size of grapefruits. The mother dragon guards her nest until the babies hatch, and some researchers have observed mothers defending their babies for short periods after they hatch. Baby dragons mostly live in trees and eat insects, lizards, birds’ eggs, and other small prey. If they want to approach a grown-up dragon’s kill to eat some of it, a baby will roll around in poop first or in the stinky parts of the dead animal’s guts so the adult dragons won’t eat the baby. Captive female dragons occasionally lay fertile eggs even though they’ve never mated, a process known as parthenogesis.

Komodo dragons look dumb. They’re probably not exactly geniuses even compared to crocodiles. But dragons kept in captivity sometimes play with items in their enclosures, which is pretty neat. If even a Komodo dragon can take time out of its busy schedule to play, you can too.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or whatever platform you listen on. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!