Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 27:21 — 28.3MB)

It’s our 100th episode! Thanks to my fellow animal podcasters who sent 100th episode congratulations! Thanks also to Simon and Julia, who suggested a couple of animals I used in this episode.

An Amazonian giant centipede eating a mouse oh dear god no:

The kouprey:

The Karthala scops owl:

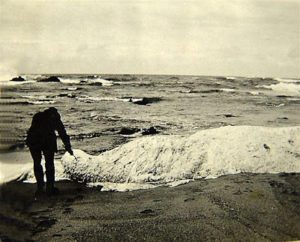

A sea mouse. It sounds cuter than it is. Why are you touching it? Stop touching it:

A sea mouse in the water where it belongs:

Mother and baby mountain goats. Much cuter than a sea mouse:

A hairy octopus:

Further reading:

Silas Claiborne Turnbo’s giant centipede account collection

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This is our 100th episode! I’ll be playing clips from some of my favorite animal podcasts throughout the show, and I highly recommend all of them if you don’t already listen!

For our big 100 show, I’ve decided to cover several animals, some mysterious, some not so mysterious, and all weird. But we’ll start with one that just seems to fit with the 100th episode, the centipede—because centipedes are supposed to have 100 legs.

So do they have 100 legs? They don’t, actually. Different species of centipede have different numbers of legs, from only 30 to something like 300. Centipedes have been around for some 430 million years and there are thousands of species alive today.

A centipede has a flattened head with a pair of long mandibles and antennae. The body is also flattened and made up of segments, a different number of segments depending on the centipede’s species, but at least 15. Each segment has a pair of legs except for the last two segments, which have no legs. The first segment’s legs project forward and end in sharp claws with venom glands. These legs are called forcipules, and they actually look like pincers. No other animal has forcipules, only centipedes. The centipede uses its forcipules to capture and hold prey. The last pair of legs points backwards and sometimes look like tail stingers, but they’re just modified legs that act as sensory antennae. Each pair of legs is a little longer than the pair in front of it, which helps keep the legs from bumping into each other when the centipede walks.

Like other arthropods, the centipede has to molt its exoskeleton to grow larger. When it does, some species grow more segments and legs. Others hatch with all the segments and legs they’ll ever have.

The centipede lives throughout the world, even in the Arctic and in deserts, which is odd because the centipede’s exoskeleton doesn’t have the wax-like coating that other insects and arachnids have. As a result, it needs a moist environment so it won’t lose too much moisture from its body and die. It likes rotten wood, leaf litter, soil, especially soil under stones, and basements. Some centipedes have no eyes at all, many have eyes that can only sense light and dark, and some have relatively sophisticated compound eyes. Most centipedes are nocturnal.

Many centipedes are venomous and their bites can cause allergic reactions in people who also react to bee stings. Usually, though, a centipede bite is painful but not dangerous. Small centipedes can’t bite hard enough to break the skin. I’m using bite in a metaphorical way, of course, since scorpions “bite” using their forcipules, which as you’ll remember are actually modified legs.

The largest centipedes alive today belong to the genus Scolopendra. This genus includes the Amazonian giant centipede, which can grow over a foot long, or 30 cm. It’s reddish or black with yellow bands on the legs, and lives in parts of South America and the Caribbean. It eats insects, spiders, including tarantulas, frogs and other amphibians, small snakes, birds, mice and other small mammals, and lizards. It’s even been known to catch bats in midair by hanging down from cave ceilings and grabbing the bat as it flies by. Because it’s so big, its venom can be dangerous to children. A four-year-old in Venezuela died in 2014 after being bitten by one, but this is unusual, and bites generally only lead to a few days of pain, fever, and swelling.

You’ll often hear that the Amazonian giant centipede is the longest in the world, but this isn’t actually the case. Its close relation, the Galapagos centipede, is substantially longer. The Galapagos Islands have EVERYTHING. The Galapagos centipede can grow 17 inches long, or 43 cm, and is black with red legs.

Another member of Scolopendra is the waterfall centipede, which grows a mere 8 inches long, or 20 cm, but which is amphibious. The waterfall centipede was only discovered in 2000, when entomologist George Beccaloni was on his honeymoon in Thailand. Naturally he was poking around looking for bugs, and I trust his spouse was aware that that’s what he would do on his honeymoon, when he spotted a dark greenish-black centipede with long legs. It ran into the water and hid under a rock, which he knew was extremely odd behavior for a centipede. They need moisture but they avoid entering water. Beccaloni noted that the centipede was able to swim in an eel-like manner. He captured it and later determined it was a new species. Only four specimens have been found so far in various parts of South Asia. Beccaloni hypothesizes that it eats insects and other small animals found in the water.

There are stories of huge centipedes found in the depths of jungles throughout the world, centipedes longer than a grown man is tall. These are most likely tall tales, since centipedes breathe through tiny notches in their exoskeleton like other arthropods and don’t have proper lungs. As we learned in the spiders episode a few months ago, arthropods just can’t get too big or they can’t get enough oxygen to live. But some of the stories of huge unknown centipedes have an unsettling ring of truth.

There are stories from the Ozark Mountains in North America about centipedes that grow as long as 18 inches, or almost 46 cm. Historian Silas Claiborne Turnbo collected accounts of giant centipede encounters in the 19th century, which are available online. I’ll put a link in the show notes.

All the accounts come across as truthful and not exaggerated at all. I think it’s worth it to read the last few paragraphs of the centipedes chapter of Turnbo’s manuscript verbatim, because they’re really interesting and I kept finding garbled accounts of the stories in various places online. Whenever possible, go to the primary source.

“R. M. Jones, of near Protem, Mo., tells of finding a centipede once imprisoned in a hollow tree. Mr. Jones said that after his father, John Jones, settled on the flat of land on the east side of Big Buck Creek in the southeast part of Taney County, his father told him one day in the autumn of 1861 to split some rails to build a hog pen. Going out across the Pond Hollow onto the flat of land he felled a post oak tree one and one-half feet in diameter. There was a small cavity at the butt of the tree. After chopping off one rail cut he found that the hollow extended only four or five feet into the rail cut, and was perfectly sound above it. After splitting the log open he was astonished at finding a centipede eight inches in length, coiled in a knot in the upper part of the cavity. At first there appeared to be no life about it. ‘I took two sticks,’ said he, ‘and unrolled it and found that it was alive. It was wrapped around numerous young centipedes which were massed together in the shape of a little ball. The old centipede was almost white in color. After a thorough examination of the stump and the ground around it, I found no place where the centipede could have crawled in. Neither, in the log, was there any place where it could enter. How it got there I am not able to explain and how long it had been an inhabitant there is another mystery to me.’

“William Patton, who settled on Clear Creek in Marion County, Ark., in 1854 and became totally blind and is dead now, says that one day while his eyesight was good he was in the woods on foot stock hunting. When about 1 ½ miles west of where the village of Powell now is, he noticed something a short distance from him crawl into a hollow tree at the ground. ‘On approaching the tree to identify the object,’ remarked Mr. Patton, ‘I saw a monster centipede lying just on the inside of the hollow which was the object I had just observed crawl into the tree. I placed the muzzle of my rifle near the opening and shot it nearly in twain, and taking a long stick I pulled it out of the hollow and finished killing it with stones. I had no way of measuring it accurately, but a close estimation proved that it was not less than 14 inches long and over an inch wide.’

“The biggest centipede found in the Ozarks that I have a record of was captured alive by Bent Music on Jimmies Creek in Marion County in 1860. Henry Onstott an uncle of the writer and Harvey Laughlin who was a cousin of mine kept a drugstore in Yellville and collected rare specimens of lizards, serpents, spiders, horned frogs and centipedes and kept them in a large glass jar which sat on their counter. The jar was full of alcohol, and the collection was put in the jar for preservation as they were brought in. Amongst the collection was the monster centipede mentioned above. It was of such unusual size that it made on almost shudder to look at it. Brice Milum, who was a merchant at Yellville when Mr. Music brought the centipede to town, says that he assisted in the measuring of it, before it was put in the alcohol and its length was found to be 18 inches. It attracted a great deal of attention and was the largest centipede the writer ever saw. The jar with its contents was either destroyed or carried off during the heat of the war. Henry Onstott died in Yellville and is buried in the old cemetery one half a mile west of town.”

There are large centipedes around the Ozarks, including the red-headed centipede that can grow over eight inches long, or 20 cm. A hiker was bitten by a six-inch red-headed centipede a few years ago in Southwestern Missouri and had to be treated at a hospital. The red-headed centipede mostly stays underground during the day, although it will come out on cloudy days. It has especially potent venom and lives in the southwestern United States and northern Mexico. And, interestingly, females guard their babies carefully for a few days after they hatch. Since the red-headed centipede is a member of the genus Scolopendra, the ones that grow so long, I wouldn’t be a bit surprised if individuals sometimes grow much longer than eight inches.

One story of a giant centipede called the upah turned out to have a much different solution. Naturalist Jeremy Holden was visiting a village in western Sumatra in the early 2000s when he heard stories of the upah. It was supposed to be a green centipede that grew up to about a foot long, or 30 cm, and had a painful bite. It was also supposed to make an eerie yowling sound like a cat. Holden discounted this as ridiculous, since no centipedes are known to make vocalizations of any kind, until he actually heard one. He was in the forest with a guide, who insisted that this was the upah. The sound came from high up in the treetops so Holden couldn’t see what was making it. But on a later trip to Sumatra with a birdwatcher friend, Holden heard the same sound, but this time the friend knew exactly what was making it. It wasn’t a centipede at all but a small bird called the Malaysian honeyguide. The honeyguide has a distinctive catlike call followed by a rattling sound, but is extremely hard to spot even for seasoned birdwatchers with powerful binoculars. This is what a Malaysian honeyguide sounds like, if you’re curious:

[honeyguide call]

The worst kind of centipede is the house centipedes. I hate those things. I’d rather have a pet spider that lives in my hair than touch a house centipede. House centipedes are the really fast ones that have really long legs that sort of make them look like evil feathers running around on the walls.

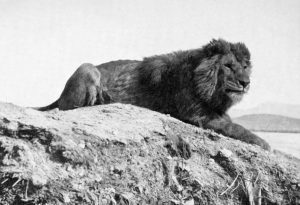

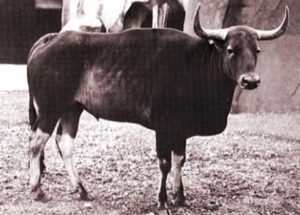

Next, let’s take a look at the kouprey, a bovine that is rare and possibly extinct. Thanks to Simon who suggested this ages ago, after the mystery cattle episode, or at least he mentioned it to me while we were talking on Twitter.

The kouprey is a wild ox from Southeast Asia and may be closely related to the aurochs. It’s big and can stand over six feet tall at the shoulder, or almost two meters. It has long legs, a slightly humped back, and a long tail. Males have horns that look like typical cow horns, but females have horns that spiral upward like antelope horns. Cows and calves are gray with darker bellies and legs, while grown bulls are dark brown with white stockings. It lives in small bands led by a female and eats grass and other plants. Males are usually solitary or may band together in bachelor groups. It likes open forest and low, forested hills. Sometimes it grazes with herds of buffalo and other types of wild ox.

The kouprey wasn’t known to science until 1937, when a bull was sent to a zoo in Paris from Cambodia. It was already rare then. A 2006 study that showed the kouprey was actually a hybrid of a domestic cow and another species of wild ox, the banteng, was later rescinded by the researchers as inaccurate. Genetic studies have since proven that the hybrid hypothesis was indeed wrong.

Unfortunately, if the kouprey still exists, there are almost none left. In the late 1960s only about 100 were estimated to still remain. While it’s protected, it’s poached for meat and horns, and is vulnerable to diseases of domestic cattle and habitat loss. The last verified sighting of a kouprey was in 1983, and there are no individuals in captivity. But conservationists haven’t given up yet. They continue to search for the kouprey in its historical range, including setting camera traps. Since the kouprey looks very similar to other wild oxen, it’s possible there are still some hiding in plain sight.

Next up, let’s look at a rare owl. Thanks to Julia who suggested the Karthala scops owl, which only lives in one place in the world. That one place in the world happens to be an active volcano. Specifically, it lives on the island of Grande Comore between Africa and Madagascar, in the forest on the slopes of Mount Karthala.

It’s a small owl with a wingspan of only 18 inches, or 45 cm. Some of the owls are greyish-brown and some are dark brown. It probably eats insects and small animals, but not much is known about it. It’s critically endangered due to habitat loss, as more and more of its forest is being cut down to make way for farmland. It sounds like this, and if you don’t think this is adorable I just can’t help you:

[owl call]

The Karthala scops owl wasn’t discovered by science until 1958, when an ornithologist named C.W. Benson found a feather living a sunbird nest. He thought it might be a nightjar feather, but it turned out to belong to an unknown owl. At first researchers thought it was a subspecies of the Madagascar scops owl, but it’s now considered to be a new species. Unlike many other scops owl species, the Karthala scops owl doesn’t have ear tufts.

That’s pretty much all that’s known about the Karthala scops owl right now. Researchers estimate there are around 1,000 pairs living on the volcano, and hopefully conservation efforts can be put into place to protect their habitat.

The sea mouse has been on my ideas list from the beginning, so let’s learn a little bit about it today too. It’s not a mouse, although it does live in the sea. It’s actually a genus of polychaete worm that lives along the coasts of the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, although it doesn’t really look like a worm. It looks kind of mouse-like, if you’re being generous, mostly because it has setae, or hairlike structures, on its back that look sort of like fur. Some species grow up to a foot long, or 30 cm, but most are usually smaller, maybe half that size or less. It’s shaped roughly like a mouse with no head or tail, and is about three inches wide, or 7.5 cm, at its widest.

The sea mouse is usually a scavenger, although at least one species hunts crabs and other polychaete worms. It spends a lot of its time burrowing in the sand or mud on the ocean bed, looking for decaying animal bodies to eat. It also has gills and antennae, although these aren’t readily noticeable because of the setae covering the animal’s back.

Underneath the setae, the sea mouse is segmented. It doesn’t have real legs but it does have appendages along its sides called parapodia, which it uses like little leglets to push itself along. Sometimes a sea mouse is found washed ashore after a storm. Often it scurries through the wet sand and looks even more like a mouse.

The most interesting thing about the sea mouse is its setae. The setae are about an inch long and are dark red, yellow, black, or brown under ordinary circumstances, depending on species. But when light shines on them just right, they glow with green and blue iridescence. The setae are hollow and made of chitin. The setae are much thinner than a human hair, and nanotech researchers have used them to create nanowires.

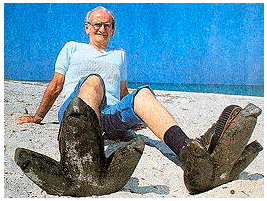

Here’s a sweet little mystery animal I got from one of my favorite books, Karl Shuker’s Search for the Last Undiscovered Animals. In 1858, French missionary Emmanuel Domenech published a book called Missionary adventures in Texas and Mexico. A personal narrative of six years’ sojourn in those regions, and in that book he mentions an interesting animal. This event apparently took place in or near Fredericksburg, Texas, sometime before about 1850. The woman in question may have been Comanche. I’ll quote the relevant passage, from pages 122 and 123 of the book.

“An American officer assured me that he had seen an Indian woman, dressed in the skin of a lion which she had killed with her own hand—a circumstance which manifested on her part no less strength than courage, for the lion of Texas, which has no mane, is a very large and formidable animal. This woman was always accompanied by a very singular animal about the size of a cat, but of the form and appearance of a goat. Its horns were rose-coloured, its fur was of the finest quality, glossy like silk and white as snow; but instead of hoofs this little animal had claws. This officer offered five hundred francs for it; and the commandant’s wife, who also spoke of this animal, offered a brilliant of great value in exchange for it; but the Indian woman refused both these offers, and kept her animal, saying that she knew a wood where they were found in abundance; and promised, that if she ever returned again, she would catch others expressly for them.”

So what could this strange little animal be? It sounds like a mountain goat. Mountain goats live in mountainous areas of western North America, but might well have been unknown elsewhere in the mid-19th century. They’re pure white with narrow black horns and hooves, but an albino individual might have horns that appear to be pinkish, at least at the base where the horn core is, due to lack of pigment in the horns allowing blood to show through the surface. While male mountain goats can grow more than three feet tall at the shoulder, or 1 meter, females are much smaller and have smaller horns. Most tellingly, mountain goats have sharp dewclaws as well as cloven hooves that can spread apart to provide better traction on rocks. To someone not familiar with mountain goats, this could look like claws rather than feet. My guess is the woman had a young mountain goat she was keeping as a pet, possibly an albino one, which would explain its size and appearance. It’s nice to think that she cared so much for her little pet that she refused huge amounts of money for it.

Let’s finish up with a rare and tiny cephalopod called the hairy octopus. It’s tiny, only two inches across, or five centimeters, and covered with strands of tissue that give it its name. The so-called hair of the hairy octopus camouflages it by making it look like a piece of seaweed or algae. It can also change colors like other octopuses, to blend in even more with its surroundings. It can appear red, brown, cream, or white, with or without spots and other patterns. It’s only ever been seen in the Lembeh Strait off the coast of Indonesia, and then only rarely.

It’s so rare, in fact, that it still hasn’t been formally described by science. So if you’re thinking about becoming a biologist and you find cephalopods like octopus and squid interesting, this might be the field for you. You might get to give the hairy octopus its official scientific name one day!

Thanks so much to all of you, whether you’re a fellow podcaster, a Patreon subscriber, a regular listener, or someone who just downloaded your first episode of Strange Animals Podcast to see if you like it. I’m having a lot of fun making these episodes, and I’m always surprised at how many people tell me they enjoy listening. I tend to forget anyone listens at all, so whenever I get an email or a review or someone tweets to me about an episode, I’m always startled and pleased. I’ve been trying hard to make the show’s sound quality better, and while I don’t always have the time to do as much research for each episode as I’d like, I do my best to make sure all the information I present is up to date and as accurate as possible.

As always, you can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening, and happy new year!