Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 17:04 — 17.1MB)

Everyone knows the legend of the unicorn and most of us know unicorns don’t really exist. But how did the legend get started? And more importantly, can we talk about narwhals a whole lot? Narwhals are rad.

Narwhal. So rad.

I haven’t seen this show but apparently it’s pretty good. I love that elasmotherium.

Unicorns are (sort of) real. Unicorning certainly is.

Thanks to Jen and Dave for suggesting this week’s topic!

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week’s episode is about the unicorn, or at least about almost-unicorns. This is a re-record of the original episode to improve sound quality and update some information.

When I was a kid, I was convinced unicorns were real. I’m not alone in this, apparently. A lot of people assume the unicorn is a real animal. Take away the magical trappings and it’s just a horse-like animal with one spiral horn. It seems a lot more plausible than squids, for instance.

I’m sorry to tell you that that kind of unicorn doesn’t exist, and never has, or at least we have no fossil or subfossil evidence that an animal resembling the classical unicorn actually existed. But the animals that probably inspired the unicorn legend are fascinating.

Everyone knows that the unicorn has one spiral horn growing from its forehead. The horn was supposed to have curative properties. If you ground up a little bit of the horn, known as alicorn, it acted as a medicine to cure you of poisoning or other ailments. If you actually made a little cup out of alicorn, you could drink from it safely knowing any poison was already neutralized. People in the olden days were really worried about being poisoned, probably because they didn’t understand how food safety and bacteria worked and they didn’t have refrigerators or meat thermometers and so forth. I suspect a lot of so-called poisoning cases were actually food poisoning. But this re-record is already off the rails, so back we get to the main topic.

All this about alicorn wasn’t legend, either. You could buy alicorn from apothecaries up until the late 18th century. Doctors prescribed it. It was expensive, though—literally worth its weight in gold. Pharmacies kept their alicorns on display but chained down so no one could steal them.

The alicorn, of course, was actually the tusk of the narwhal, and the narwhal is as mysterious as the unicorn in its own way. In fact, the narwhal seems a lot less plausibly real than a unicorn and a lot of people actually don’t realize it’s a real animal. I had that discussion with a coworker last year and had a lot of fun astonishing her with science facts, or maybe boring her. It’s a fairly small whale, some 13 to 18 feet in length not counting the tusk. That’s about four to five and a half meters long. It’s pale gray in color with darker gray or brown dapples, but like gray horses, many narwhals get paler as they age. Old individuals can appear pure white.

The narwhal and the beluga whale are similar in size and physical characteristics, such as their lack of a dorsal fin. They live in the same areas and are the only two living members of the family Monodontidae. They even interbreed very rarely.

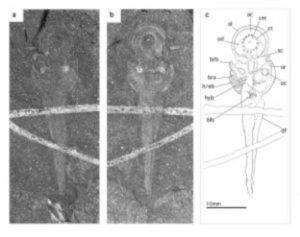

But the narwhal is the one with the horn, or more accurately a tusk. It’s not a horn at all but a tooth. Most males and about 15% of females grow a tusk. Occasionally an individual grows two tusks, but almost always it’s the left canine tooth that pierces through the lip and continues to grow, sometimes up to ten feet long, or 3 meters.

It’s a weird, weird tooth too. It can bend as much as a foot without breaking, or 30 cm, not something teeth are generally known for. It also grows in a spiral. And we still don’t know what the narwhal uses its tusk for.

For a long time, researchers assumed that male narwhals used their tusks the same way male deer use their antlers, to show off for females and to battle other males. Males do exhibit behavior called tusking, where two individuals will rub their tusks together in what researchers once assumed was a ritual fight display. But that seems not to be the case.

A 2005 study discovered that the tusk is filled with nerves and is extremely sensitive. Through its tusk, the whale can identify changes in water temperature and pressure, water salinity, and the presence of fish and other whales. It even acts as an antenna, amplifying sound. The study was led by Martin Nweeia of the Harvard School of Dental Medicine. Nweeia is a dentist, basically, which delights me. Okay, he’s a clinical instructor in restorative dentistry and biomaterials scientist, but dentist is funnier.

I liked Nweeia even more when I found this quote: “Why would a tusk break the rules of normal development by expressing millions of sensory pathways that connect its nervous system to the frigid arctic environment?” As someone who has trouble biting ice cream without wincing, I agree.

In other words, the narwhal’s tusk has scientists baffled. You hear that a lot in a certain type of article, but in this case it’s true. Especially baffling in this case is why the tusk is found mostly in males. If having a tusk confers some advantage in the narwhal’s environment, why don’t all or most females grow one too? If having a tusk does not confer an advantage beyond display for females, why does the tusk act as a sensory organ?

The narwhal lives in the Arctic, especially the Canadian Arctic and around Greenland, and it’s increasingly endangered due to habitat loss, pollution, and noise pollution. Overall increased temperature of the earth due to climate change has caused a lot of the sea ice to melt in their traditional breeding grounds, and then humans decided those areas would make great oil drilling sites. The noise and pollution of oil drilling and exploration threatens the narwhal in particular, since when a company searches for new oil deposits it sets off undersea detonations that can deafen or even outright kill whales. But it’s hard to count how many narwhals are actually alive, and some recent studies have suggested that there may be more around than we thought. That’s a good thing. Now we just have to make sure to keep them safe, because narwhals are awesome.

The narwhal eats fish and squid and shrimp and sometimes accidentally rocks, because instead of biting its prey the narwhal just hoovers it up, frequently from the sea floor, and swallows it whole. It does that because it doesn’t actually have any teeth. Besides the one.

As a final narwhal mystery, on December 17, 1892, sailors aboard a ship in the Dundee Antarctic Expedition spotted a single-horned narwhal-like whale in the Bransfield Strait. But narwhals don’t live in the Antarctic…as far as we know.

One of the reasons why so many people believe the unicorn is a real animal is because it’s mentioned in some English-language versions of the Bible. When the Old Testament was first translated from Hebrew into Greek in the third century BCE, the translators weren’t sure what animal the re’em was. It appeared in the texts a number of times but wasn’t described. The translators settled on monokeros for their translation, which in English is unicorn. The King James Version of the Bible mentions the unicorn seven times, giving it a respectability that other animals (like squids) can’t claim.

These days, Biblical scholars translate re’em as a wild ox, or aurochs. You can learn more about the aurochs in episode 58, Weird Cattle. The aurochs was the ancestor to domestic cattle and was already extinct in most parts of the world by the third century BCE, but lived on in the remote forests north of the Alps until its final extinction in 1627.

So while the Greek translators didn’t know what the re’em was, why did they decide it was a unicorn? It’s possible they were drawing on the writings of Greek physician Ctesias, from the fourth century BCE. Ctesias described an animal from India he called a type of wild ass, which had “a horn on the forehead which is about a foot and a half in length.” But it seems clear from his writing that he was describing a rhinoceros.

In fact, any description of a rhino given by someone who hasn’t actually seen one, just heard about it, comes across as a unicorn-like animal. So it’s quite likely that the translators made a wild guess that the fierce re’em was a rhinoceros, which they would have known as a horse-like animal with one horn.

But while the unicorn is mentioned in the Bible, it isn’t a specifically Christian legend. The karkadann is a huge monster in Muslim folk tradition, with a horn so big it could spear two or three elephants on it at the same time. In Siberia, some tribes told stories of a huge black ox with one horn, so big that when the animal was killed, the horn alone required its own sledge for transport. In some Chinese tales, the kilin was supposed to be a huge animal with one horn. For more information about the kilin, or kirin, you can listen to episode 61.

It’s probable that all these stories stem from the rhinoceros, which is a distinctive and unusual animal that we only take for granted today because we can go visit it in zoos. But some researchers have suggested a more exotic animal.

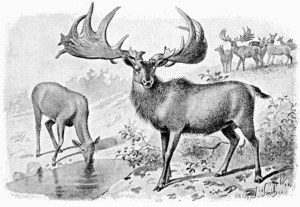

Elasmotherium was an ice age animal sometimes called the steppe rhino, giant rhino, or Siberian unicorn. The largest of the three species of elasmotherium was the size of a mammoth, some seven feet tall at the shoulder, or 2.1 meters. It was a grazer like horses and cattle today, and like them it had long legs, much longer than living rhinos. It could probably gallop at a pretty good clip. It lived at the same time as the smaller woolly rhino, but while the woolly rhino resembled modern rhinos in a lot of respects, notably its large horn on the nose with a smaller horn farther up, elasmotherium only had one horn…one enormous horn. On its forehead.

We don’t actually have any elasmotherium horns to look at. Rhino horns aren’t true horns at all but a keratin structure. Keratin is an interesting fiber. It can be immensely tough, as it is when it forms rhinoceros horns, but it’s also what our nails and hair are made of. It doesn’t fossilize any more than hair fossilizes. The main reason we know elasmotherium had a horn is because of its skull. While rhino horns are made of keratin fibers instead of bone, the skull shows a protuberance with furrows where blood vessels were that fed the tissues that generated the horn. In elasmotherium, the protuberance is five inches deep, or 13 cm, and three feet in circumference, or just over a meter. Researchers think the horn may have been five or six feet long, or 1.5 to 1.8 meters.

Researchers have also found an elasmotherium fossil with a partially healed puncture wound. It’s possible the males sparred with their enormous horns and sometimes inflicted injuries. At least it happened once.

For a long time researchers thought elasmotherium died out 350,000 years ago, much too long ago for humans to have encountered it. But a skull found a few years ago in Kazakhstan was radiocarbon dated to about 29,000 years old. If elasmotherium and humans did cross paths, it wouldn’t be at all surprising that the animal figured in stories that have persisted for millennia. More likely, though, our early ancestors found carcasses partially thawed from the permafrost the way mammoth carcasses are sometimes found today. This might easily have happened at the end of the Pleistocene, a relatively recent 11,000 years ago or thereabouts. A frozen carcass would still have a horn, and while the carcasses are long gone now, it’s not unthinkable that stories of a massive animal with a monstrous single horn were passed down to the present.

Of course, this is all conjecture. It’s much more likely that the stories are not that old and are about the modern rhinoceros. But it’s definitely fun to think about our ancestors crossing a vast hilly grassland for the first time in search of new hunting grounds, and coming across a herd of towering monsters with five-foot horns on their foreheads. That would definitely make an impression on anyone.

One final note about the unicorn. When I was a kid, I read a book called A Grass Rope by William Maine, published in 1957 so already an oldie when I found it in my local library. It concerns a group of Yorkshire kids who hunt for a treasure of local legend, which involves a unicorn. I was an American kid from a generation after the book was written, so although it’s set in the real world it felt like a fantasy novel that I could barely understand. When one of the characters discovers a unicorn skull, it didn’t seem any more extraordinary to me than anything else. But on rereading the book in my late teens, I was struck by a character at the end who tells the children “it’s not very hard to grow unicorns.”

By that time, I pretty much had Willy Ley’s animal books memorized, including the chapter about unicorns. In it, he talks about unicorning animals that have two horns.

The practice of unicorning has been known for centuries in many cultures, but the first modern experiment was conducted in 1933 by Dr. Franklin Dove in Maine. He removed the horn buds from a day-old bull calf and transplanted them to the middle of the calf’s forehead. The calf grew up, the horn buds took root and grew into a single horn that was almost completely straight and which sprouted from the bull’s forehead.

Dr. Dove reported that the bull was unusually docile, although I suspect his docility may have come from being handled more than the usual bull calf, so he became tamer than most bulls. Either way, the experiment proved that unicorning wasn’t difficult. Any animal that grows true horns, such as sheep, goats, and cattle, can be unicorned.

More recently, in the 1980s, neopagan writer Oberon Zell Ravenheart and his wife Morning Glory unicorned mohair goats that looked astonishingly like the unicorns of legend. So technically, kid me was right. Unicorns are sort of real.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us and get twice-monthly bonus episodes for as little as one dollar a month.

Thanks for listening!