Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 15:49 — 17.4MB)

Thanks to Nicholas, Måns, Warblrwatchr, Llewelly, and Emerson this week, in our yearly updates episode!

Further reading:

An Early Cretaceous Tribosphenic Mammal and Metatherian Evolution

Guam’s invasive tree snakes loop themselves into lassos to reach their feathered prey

Rhythmically trained sea lion returns for an encore — and performs as well as humans

Scientists Solve Mystery of Brown Giant Pandas

Elephant turns a hose into a sophisticated showering tool

New name for one of the world’s rarest rhinoceroses

Antarctica’s only native insect’s unique survival mechanism

Komodo dragons have iron-coated teeth to rip apart their prey

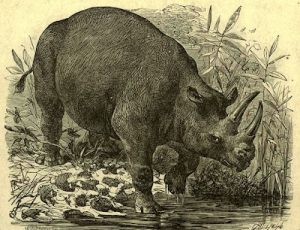

The nutria has really orange teeth:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week is our annual updates episode, and we’ll also learn about an animal suggested by Emerson. But first, we have some corrections!

Nicholas shared a paper with me that indicates that marsupials actually evolved in what is now Asia, with marsupial ancestors discovered in China. They spread into North America later. So I’ve been getting that wrong over many episodes, over several years.

Måns shared a correction from an older episode where I mentioned that humans can’t get pregnant while breastfeeding a baby. I’ve heard this all my life but it turns out it’s not true. It is true that a woman’s fertility cycle is suppressed after giving birth, but it’s not related to breastfeeding. Some women can become pregnant again only a few months after giving birth, while others can’t get pregnant again for a few years. It depends on the individual. That’s important, since the myth is so widespread that many women get pregnant by accident thinking they can’t since they’re still feeding a baby.

Warblrwatchr commented on the ultraviolet episode and mentioned that cats can see ultraviolet, which is useful to them because mouse urine glows in UV light.

Finally, Llewelly pointed out that in episode 416, I didn’t mention that fire ant venom isn’t delivered when the ant bites someone. The ant bites with its mandibles to hold on, then uses the stinger on its back end to sting repeatedly.

Now, let’s dive into some updates about animals we’ve talked about in past episodes. As usual, I don’t try to give an update on every single animal, because we’d be here all week if I did. I just chose interesting studies that caught my eye.

In episode 402, we talked about snakes that travel in unusual ways, like sidewinders. Even though I had a note to myself to talk about the brown tree snake in that episode, I completely forgot. The brown tree snake is native to parts of coastal Australia and many islands around Indonesia and Papua New Guinea. It’s not native to Guam, which is an island in the western Pacific, way far away from the brown tree snake’s home. But in the late 1940s, some brown tree snakes made their way to Guam in cargo ships and have become invasive since then.

The brown tree snake can grow up to six and a half feet long, or 2 meters, and is nocturnal, aggressive, and venomous. It’s not typically a danger to adults, but its venom can be dangerous to children and pets. The government employs trained dogs to find the snakes so they can be removed, and this has worked so well that brown tree snake population is declining rapidly on the island. But that hasn’t stopped the snake from driving many native animals to extinction in the last 75 years, especially birds.

One of the things scientists did in Guam to try and protect the native birds was to place smooth poles around the island so birds could nest on top but snakes couldn’t climb up to eat the eggs and chicks. But before long, the snakes had figured out a way to climb the poles, a method never before documented in any snake.

To climb a pole, the snake wraps its body around it, with the head overlapping the tail. Then it sort of scoots itself up the pole with tiny motions of its spine, a slow, difficult process that takes a lot of energy. Tests of captured brown tree snakes afterwards showed that not all snakes are willing or able to climb poles this way. Scientists think the brown tree snake evolved this method of movement to climb smooth-trunked trees in its native habitat. They also suspect some other species of snake can do the same.

Way back in episode 23 we talked about musical animals, including how some species can recognize and react to a rhythmic beat while most can’t. Sea lions are really good at it, especially a sea lion named Ronan.

Ronan was rescued in 2009 when she was a young sea lion suffering from malnutrition, wandering down a highway in California. She was determined to be non-releasable after she recovered, so she’s been a member of the Pinniped Lab in the University of California – Santa Cruz ever since, where she participates in activities that help scientists study sea lions. The rhythm studies are only one of the things she does, and only occasionally. The scientists put on a metronome and she bobs her head to the beat while they film her in ultra-slow motion.

The latest study was published in May of 2025. Ronan is 16 years old now and in her prime, so it’s not surprising that she performed even better than her last tests when she was still quite young. The study determined that not only does Ronan hit the beat right on time, she’s actually better at it than a human a lot of the time. She hits the beat within 15 milliseconds. When you blink your eye, it takes 150 milliseconds. If only she had hands, she’d be the best drummer ever!

The greatest thing about this process is that Ronan enjoys it. She’s rewarded with fish after a training session, and if she doesn’t feel like doing an activity, she doesn’t have to.

Back in episode 220, we talked about the giant panda, especially the mysterious Qinling panda that’s brown and tan instead of black and white. A study published in March of 2024 looked into the genetics of this unusual coat color and determined that it was a natural genetic mutation that doesn’t make the animals unhealthy, meaning it probably isn’t a result of inbreeding.

We talk occasionally about tool use in animals, especially in birds like crows and parrots, and in primates like chimpanzees. But a study published in November of 2024 detailed an elephant in the Berlin Zoo that uses a water hose to shower.

You may not think that’s a big deal, but the elephant in question, named Mary, uses the hose the way a human would to shower off. She holds the hose with her trunk just behind the nozzle, then moves it around and shifts her body to make sure she gets water everywhere she wants. She has to sling the hose backwards to clean her back, and when researchers gave her a heavier hose that she couldn’t move around as easily, she didn’t bother with it but just used her own trunk to spray water on herself.

Even more interesting, another elephant, named Anchali, who doesn’t get along with Mary, will interfere with the hose while Mary is using it. She lifts part of the hose to kink it and stop the water from flowing. Sometimes she even steps on the hose to stop the water, something the elephants have been trained not to do since zookeepers use hoses to clean out the enclosures. Anchali only steps on a hose if Mary is using it.

This is the first time researchers have studied a water hose as tool use, but it makes sense for elephants to understand how to use a hose, since they have a built-in hose on their faces.

We talked about the rhinoceros in episode 346, and more recently in the narwhals and unicorns episode. A study published in March of 2025 suggested that the Javan rhino should be classified as a new species of rhino in its own genus. The Javan rhino is incredibly rare, with only about 60 individuals alive in the world, all of them living in the wild in one part of Java. The Javan rhino is also called the Sundaic rhinoceros, and it’s been considered a close relation of the Indian rhinoceros. It’s smaller than the Indian rhino and most Javan rhino females either don’t have a horn at all or only have a big bump on the nose instead of a real horn.

The Javan rhino is so rare that we don’t really know much about it. The new study determined that there are big enough differences between the Javan rhino and the Indian rhino, in their skeletons, skin, diet, behavior, and fossil remains, that they should be placed in separate genera. The proposed new name for the Javan rhino is Eurhinoceros sondaicus instead of Rhinoceros sondaicus.

The only insect native to Antarctica is the Antarctic midge, which we mentioned in episode 221 but haven’t really talked about. It’s a flightless insect that can grow up to 6 mm long, and it’s the only insect that lives year-round in Antarctica. It’s only been found on the peninsula on the northwestern side of the continent.

Every animal that lives in Antarctica is considered an extremophile, and this little midge has some remarkable adaptations to its harsh environment. Its body contains compounds that minimize the amount of ice that forms in its body when the temperature plunges. It’s so well adapted to cold weather that it actually can’t survive if the temperature gets much above freezing. It eats decaying vegetation, algae, microorganisms, and other tiny food in its larval stages, but doesn’t eat at all as an adult.

The midge spends most of its life as a larva, only metamorphosing into its adult form after two winters. During its first winter it enters a dormant phase called quiescence, but as soon as the weather warms, it can resume development. It enters another dormant phase called obligate diapause for its second winter, where it pupates as soon as the weather gets cold. When summer arrives, all the midges emerge as adults at the same time, which allows them to find mates and lay eggs before dying a few days later.

The female midge lays her eggs and deposits a jelly-like protein on top of them. The jelly acts as antifreeze and keeps the eggs from drying out, and when the eggs hatch, the babies can eat the jelly.

In episode 384, we talked about the Komodo dragon, and only a month or so after that, and right after the 2024 updates episode, a new study was released about Komodo dragon teeth. It turns out that the Komodo dragon has teeth that are tipped with iron, which helps keep them incredibly sharp but also strong. As if Komodo dragons weren’t already scary enough, now we know they have metal teeth!

Many animals incorporate iron in their teeth, especially rodents, which causes some animals to have orange or partially orange teeth. In the Komodo dragon, the iron is incorporated into the tooth’s enamel coating, but only on the tips of the teeth. Since Komodo dragons have serrated teeth, that’s a lot of very sharp points.

There’s no way currently to test fossilized teeth to see if they once contained iron, especially since the iron would most likely be deposited in the tooth coating, the way it is for animals living today, not in the tooth itself. But because the Komodo dragon has teeth that are very similar in many ways to the teeth of meat-eating dinosaurs, scientists think some dinosaurs may have had iron in their teeth too.

And that brings us to the nutria, an animal suggested by Emerson. Emerson likes the nutria because of its orange teeth, and hopefully you can guess why its teeth are orange.

The nutria is also called the coypu, and it’s a rodent native to South America. In Spanish the word nutria means otter, so in South America it’s almost exclusively called the coypu, and the name coypu is becoming more popular in other languages too. It’s been introduced to other parts of the world as a fur animal, and it has become invasive in parts of Europe, Japan, New Zealand, and the United States.

The nutria is a semi-aquatic rodent that looks like a muskrat but is much bigger, up to two feet long, or 64 cm, not counting its tail. It also kind of looks like a beaver but is smaller. If you’re not sure which of these three animals you’re looking at, since they’re so similar, the easiest way to tell them apart is to look at their tails. The beaver has a famously flattened paddle-like tail, the muskrat’s tail is flattened side to side to act as a rudder, and the nutria’s tail is just plain old round. The nutria also has a white muzzle and chin, and magnificent white whiskers.

The nutria mostly eats water plants and is mostly active in the twilight. While it usually lives around slow-moving streams and shallow lakes, it will also tolerate saltwater wetlands. Wild nutrias are generally dark brown, but ones bred for their fur are often blond or even white.

The nutria digs large dens with the entrance usually underwater, but the nesting chamber inside is dry. It also digs for roots. This can cause a lot of damage to levees and riverbanks, which is why the nutria is so destructive as an invasive animal. It will also eat people’s gardens and commercial crops like rice and alfalfa.

One interesting thing about the nutria is that the female has teats that are high up on her sides, which allows her babies to nurse even when they’re all in the water.

The nutria’s big incisor teeth are bright orange, as we mentioned before. This is indeed because of the iron in the enamel that strengthens the teeth. Like other rodents, the nutria’s incisors grow throughout its life and are continually worn down as it chews tough plants. A nutria eats about 25% of its weight in plants every single day. That’s almost as much as me and pizza.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!