Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 18:36 — 19.0MB)

Let’s start off October with a spooky episode about some ghost animals–real ones, and some ghost stories featuring animals!

Don’t forget to enter our book giveaway! Details here.

Further reading:

What big teef you have, ghost bat:

Nom nom little ghost bat got some mealworms (also, clearly this rehabilitation worker has THE BEST JOB EVER):

Ghost snake!

This is where the ghost snake lives. This photo and the one above were both taken by Sara Ruane (find a link to the article and photos in the “further reading” section):

The ghost crab is hard to see against the sand but it can see you:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

It’s finally October, which means it’s monster month on the podcast! Let’s jump right in with an episode about three animals with the word ghost in their name, and some spooky ghost stories that feature animals. (Don’t worry, they won’t be too spooky. I don’t want to scare myself.)

First up is my personal favorite, the ghost bat. That’s, like, twice the Halloween fun in one animal! Not only that, it’s a member of a family of bats called false vampires, and is sometimes called the Australian false vampire bat. I am just, I can’t, this bat is too perfect and I have died.

The ghost bat lives in parts of northern Australia and is actually pretty big for a microbat. Its wingspan is almost 20 inches wide, or 50 cm. Its color is pale gray, sometimes almost white, while babies are darker gray. It has large, long ears and a nose leaf that helps it echolocate, and it’s nocturnal like most microbats. While it doesn’t have a tail, it does have sharp teeth and a strong jaw to help it eat even the bones of small animals.

Most microbats eat insects, but the ghost bat prefers vertebrates like frogs, mice, snakes, lizards, birds, even other species of bat. It hunts by dropping down on its prey, most of which live on the ground. It folds its wings around its prey and bites it in the neck to kill it, which makes it even better as a Halloween bat. I love this bat. It eats almost all of the body of its prey, including fur, bones, teeth, and even small feathers in the case of birds. Sometimes it eats its prey immediately, but sometimes it carries it to a small cave to eat, separate from its roosting area, referred to as a midden since the floor is littered with the remains of past meals. If you’re not familiar with the word midden, it just means a trash heap. Researchers love finding a ghost bat’s midden because they can find out exactly what animals the bat has eaten lately.

Female ghost bats roost in groups during the late spring to have their babies, usually in caves or abandoned mines. A female gives birth to a single baby, and she carries it around until it’s big enough to learn how to fly on its own, in about seven weeks. Once it can fly, it accompanies its mother on hunting trips until it’s fully weaned several months later. A mother bat has two pairs of teats, one pair near her armpits that produces milk for her baby to drink, and one pair near her legs that doesn’t produce milk. The teats near her legs act as little handholds for her baby to help it keep a good grip on her, especially when it’s very young.

The ghost bat is vulnerable to many of the usual concerns, including habitat loss and introduced predators, but it also has an unusual issue with an introduced plant and a type of fencing. The ghost bat doesn’t fly very high most of the time, since it’s usually hunting for small animals that live on the ground or birds roosting in bushes. As a result, its wings frequently get snagged on the spines of a thorny plant called lantana, and on barbed wire fencing. The spines or barbs tear the wings’ delicate patagia, often so badly that the bat can’t fly and starves to death. Since there are only an estimated 8,000 of the bats left in the wild, this is especially bad.

The ghost bat has good hearing, naturally, but it also has good eyesight. It uses a combination of hearing, vision, and echolocation to navigate and find prey. It also makes some sounds within the hearing range of humans. This is what a ghost bat sounds like:

[ghost bat chattering]

That bat sounds adorable and not spooky at all. So let’s bump up the spooky factor with our first ghost story.

This one comes from one of my favorite books, The Telltale Lilac Bush by Ruth Ann Musick, which we talked about in episode 91, about spooky owls. It’s a collection of ghost stories collected by folklorists in West Virginia. This story is called “A Loyal Dog.”

“Many years ago a small boy saw a little dog floating down the river on a log. He swam out, rescued the dog, and took it home with him. After this, the boy and the dog were together at all times. The dog lived for almost twenty years, and when it died, the young man was very sad to see his good friend go.

“Sometime later the young man was walking through a field, when all at once he was pulled down by something behind him. This gave him quite a start, but when he looked around, he saw, just in front of him, a great crack in the ground. Had he not been stopped, he would probably have fallen into it and been killed.

“What saved him, he did not know. There was nothing around that could have knocked him down or that he could have stumbled over. When he examined his clothing, however, there were the marks of a dog’s teeth on his coat, and clinging to the coat some dog hair—the same color as his old dog’s.”

Next let’s talk about the ghost snake, which lives in Madagascar. Not only is it called the ghost snake, it’s a member of a group of nocturnal or crepuscular snakes called cat-eyed snakes. The cat-eyed snakes are relatively small, slender, and have large eyes with slit pupils like cats have.

The ghost snake gets its name because it’s pale gray in color, almost white, with a darker gray pattern, and because it’s elusive and hard to find. Researchers only discovered it in 2014. A team of researchers were hiking through a national park in the pouring rain hoping to find species of snake that had never had their DNA tested. The goal was to collect genetic samples to study later. After 17 miles, or 25 km, of hiking through rugged terrain in the rain, they spotted a pale snake on the path. Fortunately they were able to catch it, and genetic analysis later showed that it was indeed a new species.

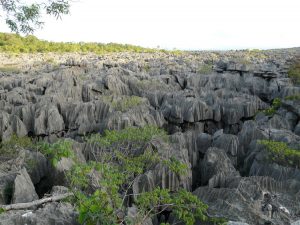

We know very little about the ghost snake since it’s so hard to find. It lives in rocky areas, which is probably why it’s pale gray, since the rocks are too. The rocks are uneven pointy limestone formations known locally as tsingy, which translates to “rock you can’t walk on barefoot.” The snake doesn’t have fangs, but it does have toxins in its saliva and a pair of enlarged teeth in the rear of the mouth. We don’t know what it eats yet, but the other cat-eyed snakes in Madagascar are general predators who eat pretty much any small animal they can catch, including frogs and toads, lizards, and rodents. Other cat-eyed snakes also sometimes act like constrictors to help kill prey.

A mysterious pale snake is definitely spooky, but I have a story that’s even spookier. It’s from a 1913 book called Animal Ghosts by Elliott O’Donnell and the story is called “The Phantom Pigs of the Chiltern Hills.”

“A good many years ago there was a story current of an extraordinary haunting by a herd of pigs. The chief authority on the subject was a farmer, who was an eye-witness of the phenomena. I will call him Mr. B.

“Mr. B., as a boy, lived in a small house called the Moat Grange, which was situated in a very lonely spot near four cross-roads, connecting four towns.

“The house, deriving its name from the fact that a moat surrounded it, stood near the meeting point of the four roads, which was the site of a gibbet, the bodies of the criminals being buried in the moat.

“Well, the B——s had not been living long on the farm, before they were awakened one night by hearing the most dreadful noises, partly human and partly animal, seemingly proceeding from a neighbouring spinney, and on going to a long front window overlooking the cross-roads, they saw a number of spotted creatures like pigs, screaming, fighting and tearing up the soil on the site of the criminals’ cemetery.

“The sight was so unexpected and alarming that the B——s were appalled, and Mr. B. was about to strike a light on the tinder-box, when the most diabolical white face was pressed against the outside of the window-pane and stared in at them.

“The children shrieked with terror, and Mrs. B., falling on her knees, began to pray, whereupon the face at the window vanished, and the herd of pigs, ceasing their disturbance, tore frantically down one of the high roads, and disappeared from view.

“Similar phenomena were seen and heard so frequently afterwards, that the B——s eventually had to leave the farm, and subsequent enquiries led to their learning that the place had long borne the reputation of being haunted, the ghosts being supposed to be the earth-bound spirits of the executed criminals.”

Our last ghostly animal is the ghost crab. There are many species of ghost crab that live all over the world, especially on tropical and subtropical beaches, including the one I’m familiar with, the Atlantic ghost crab. It’s typically a fairly small crab. The Atlantic ghost crab only grows around 2 inches across, or 5 cm, not counting its legs, while some species may be twice that size.

Its body is squarish and thick, which gives it a boxy appearance, and it has long, club-shaped eyestalks that can swivel so it can see all around it. One of its claws is always larger than the other. It digs a burrow in the sand or mud to stay in during the day, but at night it comes out and scavenges along the beach to find food. It will eat small animals if it can catch them, including insects and smaller crabs, but it also eats dead animals, rotting plants, and anything else it can find. It’s a fast runner and can zoom around on the beach at up to 10 mph, or 16 km/h.

The ghost crab gets its name from its coloration, just like the other ghost animals in this episode. Most species are white, pale gray, or pale yellow, basically the color of the sand where it lives. But it’s able to change colors to match its surroundings. This change usually takes several weeks because it has to adjust the concentration of pigments in its cells. This is useful since beaches can change color over time too.

The ghost crab is semi-terrestrial. It can’t live underwater without drowning, but it also has to keep its gills wet with seawater or it dies. This is sort of the worst of both worlds if you ask me, but it works for the crab. Generally, damp sand is wet enough to keep its gills wet, and its legs also have tiny hairlike structures that help wick moisture from the sand up to its gills.

A female ghost crab will usually join a male she likes in his burrow to mate. She carries her eggs around under her body, keeping them wet by going into the water frequently. When they’re ready to hatch, she releases them into the surf, where the larvae live until they metamorphose into little bitty young crabs that then live on land.

Surprisingly, the ghost crab makes several different sounds. It can rub the ridges on its claws together, drum on the ground with its claws, and make a weird bubbling sound. Until recently scientists weren’t sure how it made this last sound, but new research reveals that it’s made by a comblike structure in the crab’s digestive system called a gastric mill that helps grind up food. It rubs the comb of the gastric mill against another structure called a medial tooth to produce the sound. The crab uses the noises it makes to intimidate potential predators, including raccoons, and making a sound with its digestive system leaves its claws free to pinch if it needs to.

This is what the ghost crab sounds like:

[ghost crab sound]

We’ll finish up with a final spooky ghost story, or actually several short ones. I found an old but fun thread on a horse forum where people were talking about their haunting experiences in and around barns. I’ve chosen a few to read here, but if you want to go read the whole thread, I’ll link to it in the show notes.

The first comes from someone who calls themself Saidapal:

“My old mare (28 years old) and my young gelding (6 years old) were best of friends since the day he arrived at my farm when he was one. Sadly I had to have the mare put down last year. Every day for the first 2 weeks after she passed the gelding would come out of his stall and go straight to hers just like he had been doing for years to wait for her to join him. Broke my heart and still does when I think about it.

“When she had been gone for about 2-3 months I started seeing shadows out of the corner of my eyes and hearing her joints pop so I knew it was her LOL, and always the gelding would be somewhere in the vicinity. After a day or two I dreamed about her, and in the dream she was young and beautiful again. The very next morning the gelding came out of his stall and went straight to hers just like he used to. It was the last time he ever did that and I haven’t seen her since.

“I swear she had come to say goodbye to both of us.”

The next story is by Darken:

“I’ve had a number of things happen in my barn. I’ve had my collar lifted up and tugged from behind. I’ve had what felt like the nose of a big dog go into the palm of my hand, so much so that I turned around expecting to see my neighbor’s German Shepard there. And the best one was when I was walking out to the barn one night in the dark and saw the ghost of a horse run left to right between me and the barn door. Since I was looking down as I was walking, I just missed seeing its head, but I clearly saw its neck, flying mane, back, croup and flagging tail. I could see nothing below its knees, and it ran about 2 feet off the ground. The edges of it were solid white, but towards the center it was so transparent, I could see the stripes of the barn door thru it.”

And our last story is by Watermark Farm:

“Years ago I boarded at a barn where all the horses spooked badly at a certain corner near the entrance to the arena. It was a real problem and several people had been dumped badly in this corner. A boarder had a pet psychic out to work with her horse. The psychic knew nothing about this spooky spot but said ‘He hates that corner, the one with the dead pig. The dead pig thinks it’s funny to run out and scare the horses.’”

Happy Halloween!

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or just tell a friend. Don’t forget to contact me if you want to enter the book giveaway which is going on through October 31, 2020! Details are on the website.

Thanks for listening!