Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 10:19 — 11.6MB)

Further reading:

Reconstructing fossil cephalopods: Endoceras

Retro vs Modern #17: Ammonites

An endocerid [picture by Entelognathus – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=111981757]:

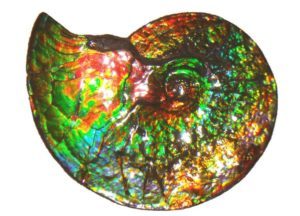

An ammonite fossil:

A hamite ammonoid that looks a lot like a paperclip [picture by Hectonichus – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=34882102]:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

When you think about cephalopods, if that’s a word you know, you probably think of octopuses and squid, maybe cuttlefish. But those aren’t the only cephalopods, and in particular in the past, there used to be even more cephalopods that are even weirder than the ones we have today.

Cephalopods are in the family Mollusca along with snails and clams, and many other animals. The first ancestral cephalopods date back to the Cambrian, and naturally we don’t know a whole lot about them since that was around 500 million years ago. We have fossilized shells that were only a few centimeters long at most, although none of the specimens we’ve found are complete. By about 475 million years ago, these early cephalopod ancestors had mostly died out but had given rise to some amazing animals called Endocerids.

Endocerids had shells that were mostly cone-shaped, like one of those pointy-ended ice cream cones but mostly larger and not as tasty. Most were pretty small, usually only a few feet long, or less than a meter, but some were really big. The largest Endoceras giganteum fossil we have is just under 10 feet long, or 3 meters, and it isn’t complete. Some scientists estimate that it might have been almost 19 feet long, or about 5.75 meters, when it was alive.

But that’s just the long, conical shell. What did the animal that lived in the shell look like? We don’t know, but scientists speculate that it had a squid-like body. The head and arms were outside of the shell’s opening, while the main part of the body was protected by the front part of the shell. We know it had arms because we have arm impressions in sections of fossilized sea floor that show ten arms that are all about the same length. We don’t know if the arms had suckers the way many modern cephalopods do, and some scientists suggest it had ridges on the undersides of the arms that helped it grab prey, the way modern nautiluses do. It also had a hood-shaped structure on top of its head called an operculum, which is also seen in nautiluses. This probably allowed Endoceras giganteum to pull its head and arms into its shell and use the operculum to block the shell’s entrance.

We don’t know what colors the shells were, but some specimens seem to show a mottled or spotted pattern. The interior of Endoceras giganteum’s shell was made up of chambers, some of which were filled with calcium deposits that helped balance the body weight, so the animal didn’t have trouble dragging it around.

3D models of the shells show that they could easily stick straight up in the water, but we also have trace fossils that show drag marks of the shell through sediment. Scientists think Endoceras was mainly an ambush predator, sitting quietly until a small animal got too close. Then it would grab it with its arms. It could also crawl around to find a better spot to hunt, and younger individuals that had smaller shells were probably a lot more active.

We talked about ammonites way back in episode 86. Ammonites were really common in the fossil record for hundreds of millions of years, only going extinct at the same time as the dinosaurs. Some ammonites lived at the bottom of the ocean in shallow water, but many swam or floated throughout the ocean. Many ammonite fossils look like snail shells, but the shell contains sections inside called chambers. The largest chamber, at the end of the shell, was for the ammonite’s body, except for a thin tube that extended through the smaller inner chambers, which allowed the animal to pump water or air into and out of the chambers in order to make itself more or less buoyant in the water.

While many ammonites were no larger than modern snails, many others were bigger than your hand, sometimes twice the size of your hand even if you have really big hands. But during the Jurassic and part of the Cretaceous, some ammonites got even bigger. One species grew almost two feet across, or 53 cm. Another grew some 4 ½ feet across, or 137 cm, and one species grew as much as 6 ½ feet across, or 2 meters. It was found in Germany in 1895 and dates to about 78 million years ago–and it wasn’t actually a complete fossil. Researchers estimate that in life it would have been something like 8 and a half feet across, or 2.55 meters.

Ammonites look a lot like a modern cephalopod called the nautilus, so much so that I thought for a long time that they were the same animal and they were all extinct. Imagine my surprise when I started researching episode 86! But although nautiluses look similar, it turns out they’re not all that closely related to ammonites. Ammonites were probably more closely related to squid, octopuses, and cuttlefish than to modern nautiluses.

Until very recently, we had no idea what the ammonite’s body looked like, just its shell. Scientists hypothesized that they had ten arms. Then, in 2021, three years after episode 86 because I have been making this podcast for a really long time, scientists found a partial fossil of an ammonite’s body. That was followed by two more discoveries of ammonite bodies, so we know a lot more about it now. We now know that ammonites resembled squid with shells a lot more than they resembled nautiluses. We still don’t know how many arms they had, but they do appear to have had two feeding tentacles like squid have, with hook-like structures that would help the ammonite hold onto wiggly prey.

Not all ammonoids had shells that resembled a snail’s spiral shell. Heteromorph ammonites had a wide variety of shell shapes. They were extremely common starting around 200 million years ago, so common that they’re used as index fossils to help scientists determine how old a particular segment of rock is. Some of the shells look a lot like ram horns, loosely coiled with ribs on the upper surface, while others were almost straight.

Baculites are a genus of ammonoid that had straight or only gently curved shells, sort of like Endocerids but living about 300 million years later and only very distantly related to them. The longest baculite shell found so far was about 6 and a half feet long, or 2 meters. Nipponites were a more complicated shape, as though a ram’s horn somehow got twisted up and crumpled into a lopsided ball. Turrilites grew in a tight spiral but with the coils on top of each other like a spiral staircase. But the best to my mind are the hamites, because some of them had shells shaped like paper clips.

We don’t know much about heteromorph ammonites, and scientists aren’t even sure how they moved around and found food. Their shell shapes would have made them slow swimmers. Many scientists now think they floated around in the water and caught tiny food as they encountered it. They even survived the end-cretaceous extinction event, although they only lived for about half a million years afterwards.

Let’s finish with a living animal, the Dana octopus squid. It’s a squid but as an adult it doesn’t have the two feeding tentacles that most squid have. It just has eight arms, which is why it’s called the octopus squid. The Dana octopus squid is a deep-sea animal that can grow quite large, although it doesn’t have very long arms. The largest specimen measured was 7 and a half feet long including its arms, or 2.3 meters, but most of that length was the mantle. The arms are only about two feet long, or 61 cm.

Because it lives in deep water, we don’t know very much about the Dana octopus squid. We know it’s eaten by sperm whales, sharks, and other large animals, and occasionally part of a dead one will wash ashore. In 2005 a team of Japanese researchers filmed a living Dana octopus squid in deep water and discovered something surprising. The undersides of the squid’s arms contain photophores that can emit light, which is pretty common in deep-sea animals. The squid’s photophores are the largest known, and now we know why.

The video showed the squid attacking the bait, and before it did, its photophores flashed extremely bright. It was so bright that the scientists think the light disorients the squid’s prey as well as allowing the squid to get a good look at where its prey is. Even better, young Dana octopus squid have been observed flashing their photophores at large predators and swimming toward them in a mock attack, startling and even scaring away a much larger animal.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!