Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 22:40 — 22.7MB)

It’s our annual updates and corrections episode, with a fun mystery animal at the end!

Thanks to everyone who contributed, including Bob, Richard J. who is my brother, Richard J. who isn’t my brother, Connor, Simon, Sam, Llewelly, Andrew Gable of the excellent Forgotten Darkness Podcast, and probably many others whose names I didn’t write down!

Further reading:

Researchers learn more about teen-age T. rex

A squid fossil offers a rare record of pterosaur feeding behavior

The mysterious, legendary giant squid’s genome is revealed

Why giant squid are still mystifying scientists 150 years after they were discovered (excellent photos but you have to turn off your ad-blocker)

We now know the real range of the extinct Carolina parakeet

Platypus on brink of extinction

Discovery at ‘flower burial’ site could unravel mystery of Neanderthal death rites

A Neanderthal woman from Chagyrskyra Cave

The Iraqi Afa – a Middle Eastern mystery lizard

Further watching/listening:

Richard J. sent me a link to the Axolotl song and it’s EPIC

Bob sent me some more rat songs after I mentioned the song “Ben” in the rats episode, including The Naked Mole Rap and Rats in My Room (from 1957!)

The 2012 video purportedly of the Lagarfljótsormurinn monster

A squid fossil with a pterosaur tooth embedded:

A giant squid (not fossilized):

White-throated magpie-jay:

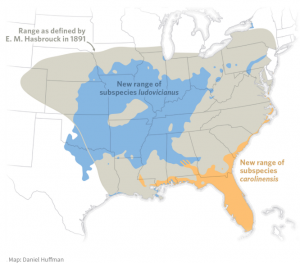

An updated map of the Carolina parakeet’s range:

A still from the video taken of a supposed Lagarfljót worm in 2012:

An even clearer photo of the Lagarfljót worm:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This is our third annual updates and corrections episode, where I bring us up to date about some topics we’ve covered in the past. We’ll also talk about an interesting mystery animal at the end. There are lots of links in the show notes to articles I used in the episode’s research and to some videos you might find interesting.

While I was putting this episode together, I went through all the emails I received in the last year and discovered a few suggestions that never made it onto the list. I’m getting really backed up on suggestions again, with a bunch that are a year old or more, so the next few months will be all suggestion episodes! If you’re waiting to hear an episode about your suggestion, hopefully I’ll get to it soon.

Anyway, let’s start the updates episode with some corrections. In episode 173 about the forest raven, I mentioned that the northern bald ibis was considered sacred by ancient Egyptians. Simon asked me if that was actually the case or if only the sacred ibis was considered sacred. I mean, it’s right there in the name, sacred ibis.

I did a little digging and it turns out that while the sacred ibis was associated with the god Thoth, along with the baboon, the northern bald ibis was often depicted on temple walls. It was associated with the ankh, which ancient Egyptians considered part of the soul. That’s a really simplistic way to put it, but you’ll have to find an ancient history podcast to really do the subject justice. So the northern bald ibis was important to the ancient Egyptians and sort of considered sacred, but in a different way from the actual sacred ibis.

In episode 146 while I was talking about the archerfish, I said something about how I didn’t fully understand how the archerfish actually spits water so that it forms a bullet-like blob. Bob wrote and kindly explained in a very clear way what goes on: “Basically, the fish spits a stream of water, but squeezes it so that the back end of the stream is moving faster than the front. So it bunches up as it flies and hits the target with one big smack. Beyond that, the water bullet would fall apart as the back part moves through the front part of the stream, but the fish can apparently judge the distance just right.” That is really awesome.

In another correction, Sam told me ages ago that the official pronouns for Sue the T rex are they/them, because that’s what Sue has requested on their Twitter profile. I forgot to mention this last time, sorry.

While we’re talking about Tyrannosaurus rex, researchers have IDed two teenaged T rex specimens found in Montana. Originally paleontologists thought the specimens might be a related species that grew to a much smaller size, Nanotyrannus, but the team studying them have determined that they were juvenile T rexes. To learn how old the specimens were and how fast they grew, they cut extremely thin slices from the leg bones and examined them under high magnification.

The study of fossil bone microstructure is called paleohistology and it’s a new field that’s helped us learn a lot about long-extinct animals like dinosaurs. We know from this study that T rex grew as fast as modern warm-blooded animals like birds and mammals, and we know that the specimens were 13 and 15 years old when they died. T rex didn’t reach its adult size until it was about twenty, and there are definite differences in the morphology of the juvenile specimens compared to an adult. The young T rexes were built for speed and had sharper teeth to cut meat instead of crush through heavy bones the way adults could. This suggests that juvenile T rexes needed to outrun both predators and smaller prey.

In other fossil news, Llewelly sent me a link about a pterosaur tooth caught in a squid fossil. We know pterosaurs ate fish because paleontologists have found fossilized fish bones and scales in the stomach area of pterosaur remains, but now we know they also ate squid. The fossil was discovered in Bavaria in 2012 and is remarkably well preserved, especially considering how few squid fossils we have. One of the things preserved in the fossil is a sharp, slender tooth that matches that of a pterosaur. Researchers think the pterosaur misjudged the squid’s size and swooped down to grab it from the water, but the squid was about a foot long, or 30 cm, and would have been too heavy for the pterosaur to pick up. One of its teeth broke off and remained embedded in the squid’s mantle, where it remains to this day 150 million years later.

And speaking of squid, the giant squid’s genome has been sequenced. Researchers want to see if they can pinpoint how the giant squid became so large compared to most other cephalopods, but so far they haven’t figured this out. They’re also looking at ways that the giant squid differs from other cephalopods and from vertebrates, including humans, to better understand how vertebrates evolved. They have discovered a gene that seems to be unique to cephalopods that helps it produce iridescence.

The Richard J. who is my brother sent me an article about giant squid a while back. There’s a link in the show notes. It has some up-to-date photos from the last few years as well as some of the oldest ones known, and lots of interesting information about the discovery of giant squid.

The Richard J. who is not my brother also followed up after the magpies episode and asked about the magpie jay. He said that the white-throated magpie jay is his favorite bird, and now that I’ve looked at pictures of it, I see why.

There are two species of magpie jay, the black-throated and the white-throated, which are so closely related that they sometimes interbreed where their ranges overlap. They live in parts of Mexico and nearby countries. They look a little like blue jays, with blue feathers on the back and tail, white face and belly, and black markings. Both species also have a floofy crest of curved feathers that looks like something a parrot would wear. A stylish parrot. Like other corvids, it’s omnivorous. It’s also a big bird, almost two feet long including the long tail, or 56 cm.

In other bird news, Connor sent me an article about the range of the Carolina parakeet before it was driven to extinction. Researchers have narrowed down and refined the bird’s range by researching diaries, newspaper reports, and other sightings of the bird well back into the 16th century. It turns out that the two subspecies didn’t overlap much at all, and the ranges of both were much smaller than have been assumed. I put a copy of the map in the show notes, along with a link to the article.

One update about an insect comes from Lynnea, who wrote in after episode 160, about a couple of unusual bee species. Lynnea said that some bees do indeed spin cocoons. I’d go into more detail, but I have an entire episode planned about strange and interesting bees. My goal is to release it in August, so it won’t be long!

In mammal news, the platypus is on the brink of extinction now more than ever. Australia’s drought, which caused the horrible wildfires we talked about in January, is also causing problems for the platypus. The platypus is adapted to hunt underwater, and the drought has reduced the amount of water available in streams and rivers. Not only that, damming of waterways, introduced predators like foxes, fish traps that drown platypuses, and farming practices that destroy platypus burrows are making things even worse. If serious conservation efforts aren’t put into place quickly, it could go extinct sooner than estimated. Conservationists are working to get the platypus put on the endangered species list throughout Australia so it can be saved.

A Neandertal skeleton found in a cave in the foothills of Iraqi Kurdistan appears to be a deliberate burial in an area where many other burials were found in the 1950s. The new skeleton is probably more than 70,000 years old and is an older adult. It was overlooked during the 1950s excavation due to its location deep inside a fissure in the cave. The research team is studying the remains and the area where they were found to learn more about how Neandertals buried their dead. They also hope to recover DNA from the specimen.

Another Neandertal skeleton, this one from a woman who died between 60,000 and 80,000 years ago in what is now Siberia, has had her DNA sequenced and compared to other Neandertal DNA. From the genetic differences found, researchers think the Neandertals of the area lived in small groups of less than 60 individuals each. She was also more closely related to Neandertal remains found in Croatia than other remains found in Siberia, which suggests that the local population was replaced by populations that migrated into the area at some point.

Also, I have discovered that I’ve been pronouncing Denisovan wrong all this time. I know, shocker that I’d ever mispronounce a word.

Now for a lizard and a couple of corrections and additions to the recent Sirrush episode. Last year, Richard J. and I wrote back and forth about a few things regarding one of my older episodes. Specifically he asked for details about two lizards that I mentioned in episode 21. I promised to get back to him about them and then TOTALLY FORGOT. I found the email exchange while researching this episode and feel really bad now. But then I updated the episode 21 show notes with links to information about both of those lizards so now I feel slightly less guilty.

Richard specifically mentioned that the word sirrush, or rather mush-khush-shu, may mean something like “the splendor serpent.” I totally forgot to mention this in the episode even though it’s awesome and I love it.

One of the lizards Richard asked about was the afa lizard, which I talked about briefly in episode 21. Reportedly the lizard once lived in the marshes near the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in what is now Iraq. Richard wanted to know more about that lizard because he wondered if it might be related to the sirrush legend, which is how we got to talking about the sirrush in the first place and which led to the sirrush episode. Well, Richard followed up with some information he had learned from a coworker who speaks Arabic. Afa apparently just means snake in Arabic, although of course there are different words for snake, and the word has different pronunciations in different dialects. He also mentioned that it’s not just the water monitor lizard that’s known to swim; other monitors do too, including the Nile monitor. I chased down the original article I used to research the afa and found it on Karl Shuker’s blog, and Shuker suggests also that the mysterious afa might be a species of monitor lizard, possibly one unknown to science. We can’t know for certain if the afa influenced the sirrush legend, but it’s neat to think about.

Next up, in cryptid news, Andrew Gable of the excellent Forgotten Darkness podcast suggested that some sightings of the White River Monster, which we talked about in episode 153, might have been an alligator—especially the discovery of tracks and crushed plants on the bank of a small island. This isn’t something I’d thought about or seen suggested anywhere, but it definitely makes sense. I highly recommend the Forgotten Darkness podcast and put a link in the show notes if you want to check it out.

And that leads us to a lake monster to finish up the episode. The Lagarfljót [LAH-gar-flote] worm is a monster from Iceland, which is said to live in the lake that gives it its name. The lake is a pretty big one, 16 miles long, or 25 km, and about a mile and a half wide at its widest, or 2.5 km. It’s 367 feet deep at its deepest spot, or 112 m. It’s fed by a river with the same name and by other rivers filled with runoff from glaciers, and the water is murky because it’s full of silt.

Sightings of the monster go back centuries, with the first sighting generally thought to be from 1345. Iceland kept a sort of yearbook of important events for centuries, which is pretty neat, so we have a lot of information about events from the 14th century on. An entry in the year 1345 talks about the sighting of a strange thing in the water. The thing looked like small islands or humps, but each hump was separated by hundreds of feet, or uh let’s say at least 60 meters. The same event was recorded in later years too.

There’s an old folktale about how the monster came to be, and I’m going to quote directly from an English translation of the story that was collected in 1862 and published in 1866. “A woman living on the banks of the Lagarfljót [River] once gave her daughter a gold ring; the girl would fain see herself in possession of more gold than this one ring, and asked her mother how she could turn the ornament to the best account. The other answered, ‘Put it under a heath-worm.’ This the damsel forthwith did, placing both worm and ring in her linen-basket, and keeping them there some days. But when she looked at the worm next, she found him so wonderfully grown and swollen out, that her basket was beginning to split to pieces. This frightened her so much that, catching up the basket, worm and ring, she flung them all into the river. After a long time this worm waxed wondrous large, and began to kill men and beasts that forded the river. Sometimes he stretched his head up on to the bank, and spouted forth a filthy and deadly poison from his mouth. No one knew how to put a stop to this calamity, until at last two Finns were induced to try to slay the snake. They flung themselves into the water, but soon came forth again, declaring that they had here a mighty fiend to deal with, and that neither could they kill the snake nor get the gold, for under the latter was a second monster twice as hard to vanquish as the first. But they contrived, however, to bind the snake with two fetters, one behind his breast-fin, the other at his tail; therefore the monster has no further power to do harm to man or beast; but it sometimes happens that he stretches his curved body above the water, which is always a sign of some coming distress, hunger, or hard times.”

The heath worm is a type of black slug, not a worm or snake at all, and it certainly won’t grow into a dragon no matter how much gold you give it. But obviously there’s something going on in the lake because there have been strange sightings right up to the present day. There’s even a video taken of what surely does look like a slow-moving serpentine creature just under the water’s surface. There’s a link in the show notes if you want to watch the video.

So let’s talk about the video. It was taken in February of 2012 by a farmer who lives in the area. Unlike a lot of monster videos it really does look like there’s something swimming under the water. It looks like a slow-moving snake with a bulbous head, but it’s not clear how big it is. A researcher in Finland analyzed the video frame by frame and determined that although the serpentine figure under the water looks like it’s moving forward, it’s actually not. The appearance of forward movement is an optical illusion, and the researcher suggested there was a fish net or rope caught under the water and coated with ice, which was being moved by the current.

So in a way I guess a Finn finally slayed the monster after all.

But, of course, the video isn’t the only evidence of something in the lake. If those widely spaced humps in the water aren’t a monstrous lake serpent of some kind, what could they be?

One suggestion is that huge bubbles of methane occasionally rise from the lake’s bottom and get trapped under the surface ice in winter. The methane pushes against the ice until it breaks through, and since methane refracts light differently from ordinary air, it’s possible that it could cause an optical illusion from shore that makes it appear as though humps were rising out of the water. This actually fits with stories about the monster, which is supposed to spew poison and make the ground shake. Iceland is volcanically and geologically highly active, so earthquakes that cause poisonous methane to bubble up from below the lake are not uncommon.

Unfortunately, if something huge did once live in the lake, it would have died by now. In the early 2000s, several rivers in the area were dammed to produce hydroelectricity, and two glacial rivers were diverted to run into the lake. This initially made the lake deeper than it used to be, but has also increased how silty the water is. As a result, not as much light can penetrate deep into the water, which means not as many plants can live in the water, which means not as many small animals can survive by eating the plants, which means larger animals like fish don’t have enough small animals to eat. Therefore the ecosystem in the lake is starting to collapse. Some conservationists warn that the lake will silt up entirely within a century at the rate sand and dirt is being carried into it by the diverted rivers. I think the takeaway from this and episode 179 is that diverting rivers to flow into established lakes is probably not a good idea.

At the moment, though, the lake does look beautiful on the surface, so if you get a chance to visit, definitely go and take lots of pictures. You probably won’t see the Lagarfljót worm, but you never know.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!