Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 14:09 — 14.9MB)

Thanks to Lorenzo for this week’s topic, carnivorous sponges! How can a sponge catch and eat animals? What is its connection to the mystery of the Eltanin Antenna? Let’s find out!

Further reading/watching:

New carnivorous harp sponge discovered in deep sea (this has a great video attached)

How Nature’s Deep Sea ‘Antenna’ Puzzled the World

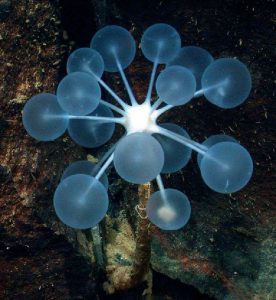

Asbestopluma hypogea, beautiful but deadly if you’re a tiny animal:

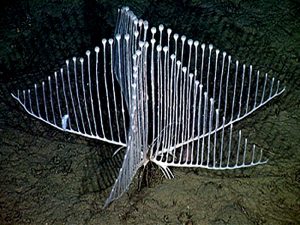

The lyre sponge, also beautiful but deadly if you’re a tiny animal:

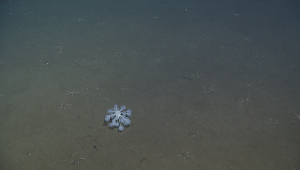

The ping-pong tree sponge, also beautiful but deadly if you’re a tiny animal:

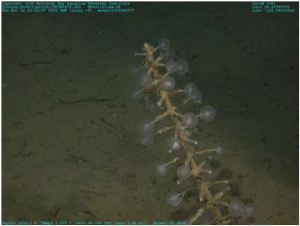

The so-called Eltanin antenna:

A better photo of Chondrocladia concrescens, looking less like an antenna and more like a grape stem:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to learn about carnivorous sponges, which is a suggestion from Lorenzo.

When I got Lorenzo’s email, I thought “oh, neat” and added carnivorous sponges to the giant, complicated list I keep of topic suggestions from listeners and my Aunt Janice, and also animals I want to learn more about. When I noticed carnivorous sponges on the list the other day, I thought, “Wait, sponges are filter feeders. Are there even any carnivorous ones?”

The answer is yes! Most sponges are filter feeders, sure, but there’s a family of sponges that are actually carnivorous. Caldorhizidae is the family, and it’s made up of deep-sea sponges that have only been discovered recently. We know there are lots more species out there because scientists have seen them during deep-sea rover expeditions without being able to study them closely.

We talked about sponges way back in episode 41, with some mentions of them in episodes 64 and 168 too, but only the filter feeder kind. Let’s first learn how a filter feeder sponge eats, specifically members of the class Demosponge, since that’s the class that the family Caldorhizidae belongs to.

Sponges have been around for more than half a billion years, since the Cambrian period and possibly before, and they’re still going strong. Early on, sponges evolved a simple but effective body plan and just stuck to it. Of course there are lots and lots and lots of different species with different shapes and sizes, but they almost all work the same way.

Most have a skeleton, but not the kind of skeleton that you think of as an actual skeleton. They don’t have bones. The skeleton is usually made of calcium carbonate and forms a sort of dense net that’s covered with soft body tissues. The tissues are often further strengthened with small pointy structures called spicules. If you’ve ever played a game called jacks, where you bounce a ball and pick up little metal pieces between each bounce, spicules sort of resemble jacks.

The sponge has lots of open pores in the outside of its body, which generally just resembles a sack or sometimes a tube. One end of the sack is attached to the bottom of the ocean, or a rock or something. The pores are lined with cells that each have a teensy structure called a flagellum, which is sort of like a tiny tail. The sponge pumps water through the pores by beating those flagella. Water flows into the sponge’s tissues, which are made up of lots of tiny connected chambers. Cells in the walls of these chambers filter out particles of food from the water, much of it microscopic, and release any waste material. The sponge doesn’t have a stomach or any kind of digestive tract, though. The cells process the food individually and pass on any extra nutrients to adjoining cells.

Obviously, this body plan is really effective for filter feeding, not so effective for chasing and killing small animals to eat. The sponge you may have in your kitchen is probably synthetic or manufactured from a sponge gourd, not an actual bath sponge animal, but it’s arranged the same way. Go look at that sponge, or just imagine it, and then compare it mentally to, say, a tiger. Very different.

But in 2007, an underwater rover captured something on film that astounded researchers. The rover was investigating some undersea caves in the Mediterranean, where a tiny sponge known as Asbestopluma hypogea lives. The sponge only grows about half an inch long, or 1.5 cm, and everyone assumed it was just a regular old sponge. You know, a filter feeder. It did have an unusual structure of filaments covered with hook-like spicules, but until 2007 no one realized those spicules were actually hooks and used to snag tiny animals like copepods, nematodes, and even brittle stars. Then they saw it on film and freaked out! Well, they probably freaked out. I like to think they did.

But wait, you are probably saying, or at least thinking, sponges don’t even have a digestive system! How do they eat the animals they catch?

It works like this. When a tiny animal floats or swims past and gets snagged by the hooked spicules, which by the way is a passive process, the sponge starts growing a membrane that envelops the animal within a few hours. The membrane is made up of specialized cells that contain beneficial bacteria, and the bacteria help digest the animal so that the cells can absorb the nutrients. The process can take up to ten days. It’s similar in some ways to how carnivorous plants digest animals, as we talked about in episode 129.

One interesting thing is that while A. hypogea is a deep-sea sponge, it’s also found in shallow underwater caves. Further research has suggested that underwater caves may shelter other animals that are usually deep-sea dwellers. One cave where the sponge is found is only 16 feet below the surface, or five meters, whereas it lives around 2,300 feet deep, or 700 meters, in open ocean. Since its discovery in both the caves and in deeper parts of the Mediterranean, it’s been classified as a protected species and parts of the Mediterranean where it lives have also been protected.

It wasn’t until 2012 that the harp sponge was discovered off the coast of northern California. The harp sponge lives up to 11,500 feet below the surface, or 3,500 m, and it gets its name because of its shape. Like a harp, which has strings stretched down from an arched frame, the harp sponge has a structure called a vane that consists of a horizontal branch with straight, thin branches growing up from it in a row. The harp sponge can have up to six vanes, and where they connect in the middle the sponge has root-like filaments that anchor it to the sea floor. It’s no wonder that people used to think sponges were plants.

The vanes of the harp sponge are covered with hooked spicules like the grabby half of Velcro, but pointier. At the top of the vertical branches, little balls of sperm form and are released into the water to fertilize the eggs of other harp sponges. The sponge also has egg development areas about halfway up the vertical branches, which have tiny filaments to help it catch sperm released by other sponges. When it catches sperm, the cells of the filament fuse with it and use it to fertilize the nearest eggs. You can see both the sperm packets and the egg development areas in a picture in the show notes, and both look like little bulbs.

I should mention that all these carnivorous sponges are incredibly pretty.

The harp sponge can grow up to almost 15 inches across, or 37 cm, which is pretty big for a sponge.

The ping-pong tree sponge is another newly discovered carnivorous sponge, and arguably it has the best name. It can grow up to 20 inches tall, or 50 cm, but most of its height comes from its central stalk that anchors it to the sea floor. At the top of the stalk, smaller stems branch out and at the end of the stalks, little bulbs around 3 to 5 mm in diameter grow like grapes on a grape stem. The bulbs resemble little ping-pong balls (also known as table tennis, but ping-pong is funnier and refers to the sound the little hollow ball makes as it bounces from a paddle and off the table).

We don’t know much at all about the ping-pong tree sponge. It’s been found off the coast of South America near Easter Island, around 8,800 feet deep, or 2,700 meters. So far it seems to live in areas where the sea floor is made up largely of hardened lava.

We’ll finish with a mystery related to carnivorous sponges! In 1964 a research ship called the USNS Eltanin was photographing the sea floor in the Antarctic, and on August 29th it took a photograph of something weird off the coast of Cape Horn. Cape Horn is the very southern tip of South America except for a few islands, and is considered the point where the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans meet. That’s an arbitrary distinction made by humans since obviously the world’s oceans are connected everywhere, but it’s useful for telling people where you found a weird thing in the water. The picture was taken at a depth of almost two and a half miles, or 3,904 meters.

The picture shows what looks like a stick growing straight up from the ocean floor, with cross-shaped pieces of equal lengths sticking straight out to the sides, and a little bulb at the very top. It looks for all the world like a weird radio antenna, and it’s actually been called the Eltanin antenna.

The picture appeared in a newspaper article later that year, 1964, and drew the attention of UFO enthusiasts. By 1968 many people thought the picture showed a piece of machinery left by alien visitors for unknown but probably sinister purposes, although why they left the machinery at the bottom of the ocean, no one could say. Other people thought the antenna had been planted by the Soviets for likewise unknown but probably sinister purposes, ditto no idea why it was at the bottom of the ocean. Other people pooh-poohed all that and said it was probably just something that had fallen off a ship and lodged upright in the mud.

Instead, it turns out that the so-called antenna is probably actually a carnivorous sponge, Chondrocladia concrescens, known to science since 1880 although no one knew it was carnivorous back then. Disappointingly, better pictures of the sponge show that it looks more like a grape stem than an antenna. These days even diehard UFO researchers acknowledge that the Eltanin antenna was just a sponge, although a pretty neat one. Mystery solved!

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!