Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 11:17 — 12.4MB)

Thanks to Sy and Finn for their suggestions this week!

Further reading:

Creeping Crinoids! Sea Lilies Crawl to Escape Predators, New Video Shows

New and Unusual Crinoid Discovered

Sea otters maintain remnants of healthy kelp forest amid sea urchin barrens

Sea urchins see with their feet

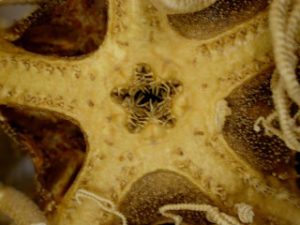

A sea lily [photo from this page]:

A feather star [still from a video posted on this page]:

Purple urchins [photo by James Maughn]:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week as we bring invertebrate August to a close, we’re going to cover some animals suggested by Finn and Sy.

We’ll start with Sy’s suggestion, crinoids, also called feather stars or sea lilies depending on what body plan a particular species has. We talked about them in episode 79 but it’s definitely time to revisit them.

Crinoids are echinoderms, a really old phylum of animals. Fossils of ancient echinoderms date back to the Cambrian half a billion years ago and they’re still incredibly common throughout the world’s oceans.

Ancient crinoids had five arms the way many starfish do, which makes sense because crinoids are related to starfish. At some point each arm developed into two, so many crinoids have ten arms or even more, and many have arms that branch. The arms are used for feeding and have feathery appendages lined with sticky mucus that traps tiny bits of food floating in the water.

There are two big divisions of crinoids today, the feather stars and the sea lilies. Feather stars are more common and can swim around as adults if they want to, although most stick to crawling along the sea floor. They swim by waving their feathery arms. Sea lilies look like flowers as adults, with a slender stem-like structure with the small body and long feathery arms at the top. I specify that sea lilies have stems as adults because a lot of feather stars also have stems as juveniles, but when they reach maturity they become free-swimming.

Even though the sea lily looks like a plant, and some species even have root-like filaments that help it anchor itself to the sea floor or to rocks, it’s still an animal. For one thing, it can uproot itself and move to a better location if it wants to, crawling with its arms and pulling its stem behind it, which is not something a plant can do except in cartoons. If a predator attacks it, the sea lily will even shed its stem completely so it can crawl away much faster. Since echinoderms in general are really good at regenerating parts of the body, losing its stem isn’t a big deal.

The biggest sea lilies today are deep-sea species, but even they only grow a stem up to about three feet long at most, or about a meter. This wasn’t the case in the ancient past, though. The longest crinoid stem fossil ever discovered was 130 feet long, or 40 meters.

Crinoids filter food particles from the water that flows through the feathery arms. Even though they look like feathers or petals, a crinoid’s arms are actually arms. They have tiny tube feet on them that act sort of like fingers to help the crinoid hold onto pieces of food, and to do a better job of holding the food, the tube feet are covered with a sticky mucus. The mouth is in the middle of the arms on the top of the body.

Crinoids absorb oxygen directly from the water. Its body contains a system of chambers and pores that are full of water, and by contracting special muscles, the crinoid moves water around in its body to transport nutrients and oxygen and to collect waste material.

Crinoids are closely related to starfish, sea cucumbers, sand dollars, and sea urchins, which brings us to Finn’s suggestion. Finn suggested urchins, which are also echinoderms. In fact, at the end of episode 79 I mentioned that one day I’d do an episode about urchins, and it only took me six years to get here!

Many urchins look like living pincushions because they’re covered in spines. That’s where the name urchin comes from, in fact. Hedgehogs, which are little round mammals with spiny backs that we talked about in episode 126, were called urchins in the olden days. Some people call the echinoderm type of urchin the sea urchin to distinguish it from the mammal type of urchin, and some people call the echinoderm urchin the sea hedgehog.

Urchins live throughout the world’s oceans, in shallow water or deep water, warm water and cold water, and there are almost a thousand species known to science. There are undoubtedly many more species yet to be discovered.

The typical urchin has a body shaped sort of like a little ball, but unlike most balls it has spines growing all over it. Depending on the species, the spines may be thin and sharp or thick and blunt. Some species even have venomous spines. Underneath, the urchin has a small area of its body that isn’t protected by spines. This is where its mouth is and its little tube feet that allow it to move around. Like crinoids and other echinoderms, it pumps water in and out of its tube feet to move them. It can also push itself off of surfaces with its spines to help it maneuver.

You may be wondering if, under its spines, an urchin has a soft body like a bouncy ball or a hard body like a baseball. Its body is actually hard, but not due to an exoskeleton. Echinoderms have an endoskeleton, meaning the hard parts of its body are on the inside like our bones are, not on the outside like a lobster’s armor. Instead of bones, echinoderms have tiny plates called ossicles that fit together like puzzle pieces and are covered with tough skin. The ossicles fit together to make the stem of a sea lily or a spiky ball in urchins, called a test.

If you look at an urchin, it’s pretty obvious it has no head or face. It’s just a little spiky ball with feet and a mouth underneath. But urchins can not only sense light and dark, at least some species can see images to some degree, and they see without eyes. Instead they have light-sensitive cells in their tube feet. Since the tube feet aren’t just for walking, and most urchins have tube feet in between spines as well as underneath, it can keep a lookout for danger with some of its feet while it’s walking around or eating with its other feet.

Unlike its crinoid cousins, the urchin isn’t a filter feeder. It mainly it eats algae and kelp but it will also eat lots of small animals, including crinoids. Its spines help keep it safe from being eaten by larger predators, but lobsters, crabs, and some kinds of starfish aren’t very worried about the spines and will eat urchins without any trouble.

One animal that specializes in eating urchins is the sea otter. The sea otter loves to eat urchins, and is good at flipping them over and biting them on their unprotected underside, or just hitting them with a rock to break off the spines. It cracks the poor urchin open like a nut and gobbles up the insides.

Because urchins like to eat kelp, and otters like to eat urchins, the kelp forests off the coast of California have always had a lot of both animals. But about a decade ago now, starting in about 2013, several things happened to alter the balance of kelp and urchin and otter. First, a disease caused the sunflower sea star to die off in great numbers, and in fact it’s still critically endangered as a result. Since that’s a type of starfish that eats a whole lot of urchins, the urchin population exploded. The next year, 2014, a heatwave over the west coast of North America caused a lot of kelp to stop growing. Kelp needs cold water to thrive. The hordes of urchins started chomping down on as much kelp as they could find, decimating more than 80% of the kelp forests in northern California before scientists even realized what was happening.

The urchin in question is the purple urchin, which lives along the eastern coast of North America. Its spines are purple and it can grow up to 4 inches across, or 10 cm. Sea otters love purple urchins so much that sometimes their teeth turn purplish in color from eating so many.

The sea otters responded to the population explosion by turning into urchin-eating maniacs, eating up to four times as many urchins as usual. The problem is that the sea otter population is still rebounding from being hunted nearly to extinction in the early 20th century, and they’re still an endangered species. There just weren’t enough otters to eat all the urchins.

Scientists studying the situation noticed something strange. The otters were only eating urchins where the kelp forests were still healthy. They ignored all the millions of urchins where the kelp forests had been eaten down to the ground, even though the urchins didn’t have anywhere to hide from hungry otters. The scientists discovered that the urchins in what they called urchin barrens were basically starving to death. There were far too many urchins and no food left for them to eat. That meant they weren’t as nutritious, so the otters didn’t bother to eat them.

The result was actually positive. The balance of urchins and sea otters and healthy kelp was maintained, so the urchin barrens didn’t get any worse. The kelp forests will rebound, although it will take a long time. Everybody say hello to the otters, and goodbye to all the extra urchins.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or whatever platform you listen on. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!