Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 9:19 — 10.4MB)

Further reading:

The Trees That Miss the Mammoths

The disappearance of mastodons still threatens the native forests of South America

Study reveals ancient link between mammoth dung and pumpkin pie

A mammoth, probably about to eat something:

The Osage orange fruit looks like a little green brain:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

Way back at the end of 2017, I found an article called “The Trees That Miss the Mammoths,” and made a Patreon episode about it. In episode 320, about elephants, which released in March of 2023, I cited a similar article connecting mammoths and other plants. Now there’s even more evidence that extinct megafauna and living plants are connected, so let’s have a full episode all about it.

Let’s start with the Kentucky coffeetree, which currently only survives in cultivation and in wetlands in parts of North America. It grows up to 70 feet high, or 21 meters, and produces leathery seed pods so tough that most animals literally can’t chew through them to get to the seeds. Its seed coating is so thick that water can’t penetrate it unless it’s been abraded considerably. Researchers are pretty sure the seed pods were eaten by mastodons and mammoths. Once the seeds traveled through a mammoth’s digestive system, they were nicely abraded and ready to sprout in a pile of dung.

There are five species of coffeetree, and the Kentucky coffeetree is the only one found in North America. The others are native to Asia, but a close relation grows in parts of Africa. It has similar tough seeds, which are eaten and spread by elephants.

The African forest elephant is incredibly important as a seed disperser. At least 14 species of tree need the elephant to eat their fruit in order for the seeds to sprout at all. If the forest elephant goes extinct, the trees will too.

When the North American mammoths went extinct, something similar happened. Mammoths and other megafauna co-evolved with many plants and trees to disperse their seeds, and in return the animals got to eat some yummy fruit. But when the mammoths went extinct, many plant seeds couldn’t germinate since there were no mammoths to eat the fruit and poop out the seeds. Some of these plants survive but have declined severely, like the Osage orange.

The Osage orange grows about 50 or 60 feet tall, or 15 to 18 meters, and produces big yellowish-green fruits that look like round greenish brains. Although it’s related to the mulberry, you wouldn’t be able to guess that from the fruit. The fruit drops from the tree and usually just sits there and rots. Some animals will eat it, especially cattle, but it’s not highly sought after by anything. Not anymore. In 1804, when the tree was first described by Europeans, it only grew in a few small areas in and near Texas. The tree mostly survives today because the plant can clone itself by sending up fresh sprouts from old roots.

But 10,000 years ago, the tree grew throughout North America, as far north as Ontario, Canada, and there were seven different species instead of just the one we have today. 10,000 years ago is about the time that much of the megafauna of North and South America went extinct, including mammoths, mastodons, giant ground sloths, elephant-like animals called gomphotheres, camels, and many, many others.

The osage orange tree’s thorns are too widely spaced to deter deer, but would have made a mammoth think twice before grabbing at the branches with its trunk. The thorns also grow much higher than deer can browse. Trees that bear thorns generally don’t grow them in the upper branches. There’s no point in wasting energy growing thorns where nothing is going to eat the leaves anyway. If there are thorns beyond reach of existing browsers, the tree must have evolved when something with a taller reach liked to eat its leaves.

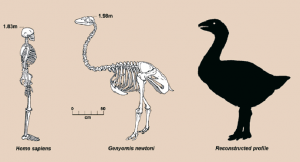

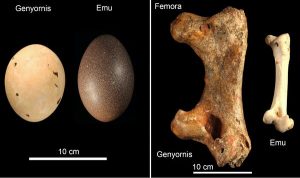

The term “evolutionary anachronism” is used to describe aspects of a plant, like the Osage orange’s thorns and fruit, that evolved due to pressures of animals that are now extinct. Scientists have observed evolutionary anachronism plants throughout the world. For instance, the lady apple tree, which grows in northern Australia and parts of New Guinea. It can grow up to 66 feet tall, or 20 meters, and produces an edible red fruit with a single large seed. It’s a common tree these days, probably because the Aboriginal people ate the fruit, but before that, a bird called genyornis was probably the main seed disperser of the lady apple.

In episode 217 we talked about the genyornis, a flightless Australian bird that went extinct around 50,000 years ago but possibly more recently. It grew around 7 feet tall, or over 2 meters, and recent studies suggest it ate a lot of water plants. It would have probably eaten the lady apple fruit whenever it could, most likely swallowing the fruits whole and pooping the big seeds out later.

Way back in episode 19 we talked about a tree on the island of Mauritius that relied on the dodo’s digestive system to abrade its seeds so they could sprout. It turns out that study was flawed and the seeds don’t need to be abraded to sprout. They just need an animal to eat the flesh off the seed, either by just eating the fruit and leaving the seed behind, or by swallowing the entire fruit and pooping the seed out later, and that could have been done by any number of animals. The dodo probably did eat the fruits, but so did a lot of other animals that have also gone extinct on Mauritius.

In June of 2025, a study was published showing that the gomphothere Notiomastodon, which lived in South America until about 10,000 years ago, definitely ate fruit. Notiomastodon was an elephant relation that could probably grow almost ten feet tall, or 3 meters. It probably lived in family groups like modern elephants and probably looked a lot like a modern elephant, at least if you’re not an elephant expert or an elephant yourself. The 2025 study examined a lot of notiomastodon teeth, and it discovered evidence that the animals ate a lot of fruit. This means it would have been an important seed disperser, just like the African forest elephant that we talked about earlier.

Another plant that nearly went extinct after the mammoth did is a surprising one. Wild ancestors of modern North American squash plants relied on mammoths to disperse their seeds and create the type of habitat where the plants thrived. Mammoths probably behaved a lot like modern elephants, pulling down tree limbs to eat and sometimes pushing entire trees over. This disturbed land is what wild squash plants loved, and if you’ve ever prepared a pumpkin or squash you’ll know that it’s full of seeds. The wild ancestors of these modern cultivated plants didn’t have delicious fruits, though, at least not to human taste buds. The fruit contained toxins that made them bitter, which kept small animals from eating them. Small animals would chew up the seeds instead of swallowing them whole, which is not what the plants needed. But mammoths weren’t bothered by the toxins and in fact probably couldn’t even taste the bitterness. They thought these wild squash were delicious and they ate a lot of them.

After the mammoth went extinct, the wild squash lost its main seed disperser. As forests grew thicker after mammoths weren’t around to keep the trees open, the squash also lost a lot of its preferred habitat. The main reason why we have pumpkins and summer squash is because of our ancient ancestors. They bred for squash that weren’t bitter, and they planted them and cared for the plants. So even though the main cause of the mammoth’s extinction was probably overhunting by ancient humans, at least we got pumpkin pies out of the whole situation. However, I personally would prefer to have both pumpkin pie and mammoths.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!