Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 14:41 — 14.9MB)

We’re discovering which animals are the tallest this week! This episode includes our first dinosaur!

Sauroposeidon proteles:

Giraffes:

Bop bop bop have at thee!

Paraceratherium (I couldn’t find one that I liked so I drew one, along with a giraffe and ostrich to scale):

Ostrich running:

I SAID DON’T @ ME

A fine day at the ostrich races. I could not make this stuff up if I tried:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re looking at tall animals. Is the giraffe the tallest mammal that’s ever lived? Is the ostrich the tallest bird? And what about tall dinosaurs?

I don’t talk about dinosaurs much in this podcast because there are so many good podcasts devoted specifically to dinosaurs. I recommend I Know Dino. It’s family friendly and goes over the latest dinosaur news without talking down to listeners or dumbing down the information.

Four-footed animals are usually measured at the shoulder, since some animals hold their heads low, like bison, while others hold their heads high, like horses. But we’re talking about tall animals today, and that includes animals with long necks. So the measurements here are all from head to toe, with the head and neck held in its natural standing position.

Let’s start with the real biggie, the tallest dinosaur ever found.

In 1994 a guy named Bobby Cross noticed some fossils weathering out of the ground at the Oklahoma correctional facility where he worked as a dog trainer. As he always did when he found fossils, he called the Oklahoma Museum of Natural History. They sent a team to take a look. The team found four vertebrae, but they were just so big—around four feet long each, or 120 cm—that at first they thought they must be fossilized tree trunks.

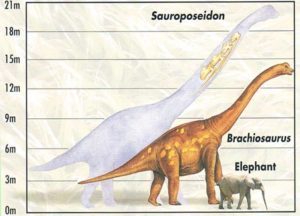

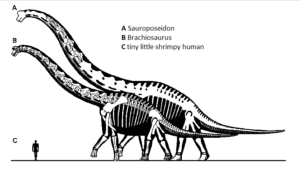

Sauroposeidon proteles was probably closely related to Brachiosaurus, but was even bigger and taller. Sauroposeidon stood 60 feet tall, or 18 meters, and its neck alone was 39 feet long, or 12 meters. Its body and legs were relatively short and stocky. We don’t have a complete skeleton, just the four vertebrae found in southeastern Oklahoma, and a few vertebrae from two other individuals found in Montana and Texas. A trail of giant footprints in Texas may be a Sauroposeidon track too. But for sauropods, neck vertebrae are the most valuable fossils because they tell so much about the animal.

Sauroposeidon’s neck bones were massive, but they were lighter than they look due to tiny air sacs in the bones, like those in bird bones. The air sacs in bird bones actually contain air that flows through the lungs, called pneumatic bones, which provides the bird with more oxygen. A CT scan of the Sauroposeidon fossils—at least the portions of the fossils that would actually fit in the CT scanner—revealed that sauroposeidon’s vertebrae were constructed in the same way that bird bones are. We know that pterosaurs and theropods had pneumatic bones, so it’s not too surprising that at least some sauropods did too.

Sauroposeidon lived around 110 million years ago, during the Mesozoic era, specifically during the early to mid Cretaceous. The sea level was much higher then than it is now, so Sauroposeidon lived near the coast. It ate plants, and like many birds, it also swallowed stones to help it digest those plants, called gastroliths. Paleontologists have found lots of sauropod gastroliths associated with fossil animals. Unlike mammals, which chew their food before swallowing, sauropods swallowed it whole and the plant material was broken up in a stomach or gizzard-like structure. That’s why its head is so small relative to its body, and how it could eat enough plants to keep such an enormous body going. It probably ate literally a ton of food every single day.

We know a lot about sauropods, and since sauroposeidon appears to be structurally typical of other sauropods, just really big, it’s a safe bet to assume it was like other sauropods in many ways. It probably nested in groups and laid about two dozen eggs at a time in big nests on the ground. We don’t have any sauroposeidon eggs, but they probably wouldn’t have been all that big, maybe about the size of a football. Babies would have grown rapidly and were full grown in ten to twenty years. Sauroposeidon migrated in herds throughout the year, traveling from nesting grounds to new grazing grounds. While it lived near the ocean, it would have had to be careful about walking on soft ground. An animal that tall and heavy can get mired in mud easily. Paleontologists have actually found fossils of sauropods that died standing up, unable to climb out of a muddy hole after sinking in soft ground.

Giraffes are the tallest living animals today, with the tallest recorded giraffe, a male, measuring 19.3 feet, or 5.88 meters. That’s pretty darn tall, about 1/3 the height of sauroposeidon. Giraffes are related to deer and cattle, and live in the savannahs and forests of Africa, where they eat tree leaves that are much too high off the ground for other animals to reach. Female giraffes and their young make up loose groups, while males form groups of their own. While giraffes can kick hard enough to kill lions, when males fight over females, they use their necks. A male will swing its head at another male, and the two will tussle back and forth bopping necks together. As a result, male giraffes have thicker, stronger necks than females. Males are also usually taller than females.

The giraffe not only has a long neck and long legs, it has a long tongue that it uses to grab leaves that are juuuust too far away. The tongue is about 18 inches long, or 45 cm. A giraffe at Knoxville Zoo licked my hair once. The giraffe’s upper lip is also prehensile, and is hairy as a protection from thorns. Because of all the thorns it encounters, giraffe skin is surprisingly tough. The giraffe has large eyes that give it good vision, and it also has keen hearing and smell. It can close its nostrils to protect them from dust, sand, insects, and—you guessed it—thorns. So many thorns. And giraffe fur contains natural parasite repellents, which also makes giraffes smell funny.

All this is pretty awesome, but we’re not done with giraffe awesomeness. Giraffes have skin-covered horns called ossicones. Females and males both have ossicones, although males also have a median lump at the front of the skull that’s not exactly an ossicone but is sort of like one. Some females also have this median lump. Ossicones are made of cartilage that has ossified, or turned boney, and they’re covered in skin and hair, although since males use their ossicones in necking fights, they tend to rub all the hair off and have bald ossicones.

The only other animal alive today that has ossicones is the okapi, a close relative of the giraffe, but giraffe ancestors once had all kinds of weird ossicones. Xenokeryx amidalae, for instance, which lived about 16 million years ago in what is now Spain, had two ossicones over its eyes, and a third sticking up from the back of its head that was T-shaped. The name amidalae comes from the character Padme Amidala in Star Wars: The Phantom Menace, if you remember that weirdly shaped headdress she wore.

Because giraffes are so tall, they have some physical adaptations that are unique among mammals living today. A giraffe has the same number of neck bones as all other mammals except sloths and manatees, which are weird, but the vertebrae are much longer than in other mammals, almost a foot long, or 28 cm. The giraffe can also tilt its head right back until it’s just about in line with the back of the neck. I’m picturing everyone listening tilting their heads back right now, and hopefully you notice how the back of your neck curves when you look up. Also, please don’t wreck your car because you’re looking up while driving. The giraffe’s circulatory system is really unusual. Its heart is enormous and beats around 150 times per minute. The jugular veins, which are the big veins that carry blood up the neck to the brain, have valves that keep blood from running backwards when a giraffe lowers its head to drink.

Giraffes can walk, and giraffes can run, but they don’t have any other gaits. They can’t trot or canter, for instance. Even humans have more than two gaits, because we can skip. Despite its height, a giraffe can really move. It can run over 30 miles per hour, or about 50 km per hour, and keep it up for several miles. It has cloven hooves. Because a giraffe’s body is so heavy and its legs so long and thin, it has specialized ligament structures in its legs that keep them from collapsing. Horses also have this structure, which also helps the animal sleep while standing.

Oh, and the giraffe doesn’t eat leaves all the time. It spends a lot of the day just standing around chewing its cud.

There used to be a mammal that stood almost as tall as the giraffe at the shoulder. Paraceratherium orgosensis went extinct around 23 million years ago, and it’s not even related to the giraffe. It’s a member of the rhinoceros family. Like sauroposeidon, we don’t have a complete skeleton of paraceratherium, so its size is an estimate based on the proportions of closely related animals whose sizes we do know. It probably stood 18 feet high at the shoulder, or 5.5 meters, and while its neck was probably around 7 feet long, or a little over 2 meters, it probably held it forward like a rhino instead of up like a giraffe, so it didn’t add much to the animal’s overall height.

In episode 32 we learned about the giant moa, a flightless bird that once lived in New Zealand. It was probably the tallest bird that ever lived, with big females 12 feet tall, or 3.6 meters. But the tallest living bird is the ostrich. It also lives in Africa and is famous for being flightless and for being able to run really fast. In fact, it’s not only the tallest bird alive, it’s the fastest. It can run over 40 miles per hour, or about 70 km per hour, and it uses its large wings as rudders and even to help it brake. With its head raised, a big ostrich can be nine feet tall, or 2.8 meters.

There are a lot of differences between ostriches and most other birds. Most birds have four toes, for instance. The ostrich has two, one large toe with a hoof-like nail, and a smaller outer toe with no nail at all. All other living birds secrete urine and feces together, but the ostrich secretes them separately the way mammals do. And while most male birds don’t have a penis, the male ostrich does. And the ostrich has a double kneecap. Not only is that unique to birds, it’s unique to everything. No other animal known, living or extinct, has a double kneecap. Researchers have no idea what it’s for, although one hypothesis is that it allows a running ostrich to extend its legs farther, and another hypothesis is that it might protect tendons in the bird’s leg.

The ostrich eats plants, seeds, and sometimes insects. Like Sauroposeidon and many other dinosaurs and birds, the ostrich swallows small rocks and pebbles to help digest its food in its gizzard. The gizzard contracts, smashing the gastroliths and plants together to help break up the plant material the way mammals would chew it.

Ostrich eggs are the biggest laid by any living bird, about six inches long, or 15 cm. Females lay their eggs in a communal nest.

Ostriches are farmed like big chickens, for their feathers, meat, and skin for leather. Ostriches are also sometimes ridden and raced with special saddles and bridles. But ostriches aren’t easy birds to manage. They can be aggressive, and they can kill a human with one kick.

To wrap things back around to dinosaurs, some researchers think many fast-running dinosaurs used their feathered forelimbs the way ostriches use their wings, to help maneuver and possibly to help keep unfeathered portions of the body warm at night. During the day, when it’s hot, ostriches keep their wings raised so that their unfeathered upper legs can release heat into the atmosphere, but at night they cover their upper legs to retain heat. It’s just another link between birds and their long-distant ancestors, the dinosaurs.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or whatever platform you listen on. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!