Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 18:44 — 21.5MB)

Sign up for our mailing list! We also have t-shirts and mugs with our logo!

Further reading:

Million-year-old mammoth genomes shatter record for oldest ancient DNA

Mammoth Genome Project (with pictures of cave art and ancient carvings of mammoths)

The most famous cave painting of a mammoth, from a cave in France:

Sivatherium:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

It’s the last Monday of 2021, which means the very last extinction event episode. There’ve been way more extinction events in earth’s long history than the five we’ve covered this year, and not all of the extinction events I chose to highlight were even necessarily the biggest. This one, for instance.

You may have noticed a pattern when I talk about ice age megafauna. So many animals went extinct about 11,000 years ago. That’s this week’s topic, the end-Pleistocene extinction event.

The Pleistocene is often called the ice age, or ice ages since it consisted of multiple glaciation periods separated by warmer times when the glaciers would retreat for a while. It started roughly 2.6 million years ago and is considered to have ended 11,700 years ago. Keep in mind, as always, that these dates are just a shorthand to help scientists refer to changes in earth’s history. There was no one day where the sun rose and everything had abruptly changed from one era to another. The changes took place over a long time, hundreds of thousands of years, with different parts of the world changing more quickly or slowly than others depending on local conditions.

At the beginning of the Pleistocene, the world’s continents were roughly in their present positions. Two continental plates in what is now Central America collided very slowly over millions of years, which caused the land to buckle up and magma to erupt through the earth’s crust as volcanoes. The volcanoes created islands in the Central American Seaway, a section of ocean between North and South America that connected the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. By around 5 to 10 million years ago, the volcanoes and land continued to be pushed up, and sediment from rivers filled in between them, until finally instead of islands there was actual land that connected North and South America. That land is called the Isthmus of Panama and it allowed the great American interchange where animals from North America could cross into South America, and vice versa, but that’s a topic for another episode.

Another result of the Isthmus of Panama’s formation is that the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans were more separated. Instead of ocean currents circulating between North and South America, they were cut off and new currents formed. Ocean currents help distribute warm water to colder areas and cold water to warmer areas, which affects air and land temperatures too. Around 2.5 million years ago, the ocean current changes had changed the entire overall temperature of the earth, making it much cooler overall. That wasn’t the only cause of the ice ages, but it was a major factor.

The earth gradually became cooler and dryer, a process that had already started due to other causes and was accelerated by the ocean current changes. As the global temperature dropped, more and more water was locked up in huge glaciers called ice sheets, at first around the poles and then farther south. This meant sea levels dropped a lot. North America was connected to Asia by a stretch of grassland steppe called Beringia that had formerly been submerged.

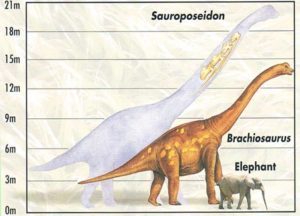

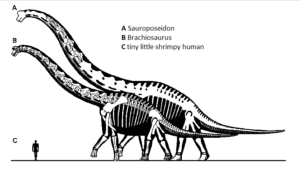

As the temperatures dropped and the climate changed, animals and plants had to adapt. The ancestors of modern elephants had lived in Africa for millions of years, but they started migrating to other parts of the world around 3 million years ago. Because they were already big, they were good at retaining heat in their bodies and became quite successful as the climate grew cooler and cooler. They evolved long hair to stay even warmer and spread throughout much of the world, including Europe, Asia, and North America. You may know them as mammoths, which were closely related to the modern Asian elephant. The first mammoth known was the South African mammoth that lived around 5 million years ago and stood about 12 feet tall at the shoulder, or 3.7 meters.

We actually know a lot about the various species of mammoth because we have so many remains. Our own distant ancestors left cave paintings and carvings of mammoths and other animals in many parts of the world, we’ve found lots of fossilized remains, and we have lots of subfossil remains too. Because the mammoth lived so recently and sometimes in places where the climate hasn’t changed all that much in the last 10,000 years, namely very cold parts of the world with deep layers of permafrost beneath the surface, sometimes mammoth remains are found that look extremely fresh.

Before people understood extinction and related natural concepts, some people who lived in areas where dead mammoths occasionally weathered out of the permafrost thought they’d only died recently. That’s how fresh the dead animals looked. The people didn’t know what the animals were, though, and assumed that since they were only ever seen partially buried, they must be underground animals. In parts of Siberia, people thought mammoths lived underground and if they accidentally came to the surface, they died.

In February of 2021, a genetic study of mammoth DNA found in teeth was published in Nature. Nature is one of the most important scientific journals in the world and they don’t just publish any old genetic study these days, now that DNA is so much easier to sequence than it used to be. In this case, though, the DNA came from three mammoth teeth that were more than one million years old and possibly around 1.5 million years old. The teeth were found in the 1970s in different places. Before DNA was successfully found in the teeth, the oldest DNA sequenced was from a horse bone that was about 780,000 years old at the most.

Genetic material breaks down relatively quickly once an animal dies, becoming more and more fragmented as the years pass by. That’s why we don’t have any dinosaur DNA—they just lived too long ago for any usable genetic material to remain. The mammoth genetic study is a big deal since it’s pushed back scientists’ ability to sequence ancient DNA, at least of some samples. In the case of both the mammoth teeth and the ancient horse bone, the remains were preserved in permafrost that slowed the fragmentation of the DNA.

The study found that one of the teeth belonged to an early woolly mammoth and the other two were from early steppe mammoths, but it’s not as simple as it sounds. The two steppe mammoth teeth looked alike but their genetic story was very different. One had genetic markers that identified it as an ancestor of woolly mammoths–but the other didn’t. The one that didn’t is called the Krestovka sample and was found in Russia. Researchers aren’t sure yet if it’s actually a new species or subspecies, but it was obviously part of a population isolated from other steppe mammoths.

But it gets even more complicated, because Columbian mammoths from North America do show that some of their ancestors were related to the Krestovka sample–and Columbian mammoths are also related to woolly mammoths. Researchers suspect that the Columbian mammoth was a species that developed from hybrids of the Krestovka steppe mammoths and woolly mammoths. Over half a million years ago, there were enough of these hybrid mammoths that they were actually numerous enough to form their own stable species. Hybrid speciation is still a relatively new concept but as genetic studies get more sophisticated, we’re getting more evidence of it happening.

Researchers are hopeful that even older genetic samples can eventually be sequenced, but there’s a hard limit to DNA found in permafrost. That limit is 2.6 million years, which is when the permafrost began forming. And that brings us back to the ice age.

Mammoths weren’t the only animals adapted to cold conditions, of course. They weren’t even the only elephant lineage that adapted to the cold. Mastodons aren’t actually that closely related to mammoths but they are an elephant relation.

The woolly rhinoceros was about the size of living rhinoceros species but was covered in thick fur. It had a massive hump on its shoulders that was made up of fat reserves and muscle, much like modern bison. It went extinct about 10,000 years ago.

A giraffe relation, Sivatherium, lived in Africa and parts of Asia during the Pleistocene. Its neck wasn’t as long as a modern giraffe’s but it was still tall, over 7 feet tall at the shoulder, or more than 2 meters, and almost 10 feet tall including the head and neck, or 3 meters. The males had two pairs of ossicones that resembled antlers, a large pair on its head and a smaller pair over its eyes. Ossicones are bony projections usually covered with skin and hair, and modern giraffes have ossicones too.

Mammals weren’t the only megafauna, though. Mega just means big, and fauna just means animal. There were megafauna birds and reptiles too, such as the Asian ostrich. It lived throughout much of Asia and the Middle East until around 8,000 years ago and was related to the modern ostrich. The wonambi was an Australian constrictor snake, not related to the snakes living in Australia now, that could grow up to 30 feet long, or 9 meters.

So what happened to cause the extinction of all these amazing animals? Surely we know more about this extinction event than we do about older ones since it happened so recently, right?

Actually, no. Although it feels significant to us now, the end-Pleistocene extinction event actually wasn’t very big compared to the others we’ve discussed this year. A lot of ice age megafauna are still around, including bears, wolves, moose, reindeer, horses, bison, elephants, giraffes, lions, tigers, camels, kangaroos, tapirs, ostriches, condors, and lots more. Even humans are ice age megafauna since we spread throughout the world during the Pleistocene.

We do have hints of what might have caused the end-Pleistocene extinction event, and one big hint comes from what happened in Australia. Like the rest of the world, Australia’s climate was cooler and dryer during the ice ages and animals that had adapted to the cold lived throughout the continent. This included diprotodon that we talked about in episode 224, along with kangaroos, wombats, koalas, and other marsupial mammals that were bigger than the ones living today. But extinctions in Australia started a lot earlier than they did in the rest of the world, around 45,000 years ago. There’s also no corresponding extinction event among marine animals. By about 40,000 years ago almost 90% of all species of Australian megafauna had gone extinct, while smaller animals and marine animals were mostly just fine.

One specific event that happened around 45,000 years ago was the colonization of Australia by humans. Humans had visited and even lived in Australia as far back as 70,000 years ago, but by 45,000 years ago they were really spreading throughout the land. The animals of Australia had never encountered smart, fast tool-users before and didn’t know what to do except try to avoid them. Humans had weapons like spears that could kill at long range, and humans worked together to kill animals that before then had no predators due to their size. Humans also drink a lot of water because we developed in a part of Africa where water is abundant. Fresh water isn’t nearly as abundant in Australia, so humans would stake out water sources and keep other animals away.

The Australian extinctions were probably a combination of climate change, humans hunting large animals that reproduced slowly, and humans outcompeting animals for water sources. The same causes probably led to extinctions in other parts of the world, but because humans took longer to spread to continents like the Americas that are far away from Africa, those extinctions mostly took place later than in Australia. It’s also important to note that Africa showed almost no extinctions at the end of the Pleistocene. Researchers think this is because the animals of Africa evolved alongside humans and knew how to deal with us.

Natural climate change was definitely a contributing cause to the extinctions, though. Ice sheets melted, glaciers retreated, and the world warmed over the course of just a few thousand years. Animals that were well adapted to the cold had to move to places where it was still cold, but those places didn’t always have the right foods or enough food. The sea levels rose too, cutting off access to parts of the world. Beringia became covered with ocean again, for instance, where it remains today, separating Asia from North America.

Humans probably finished off the mammoths by hunting the last ones to extinction, but some populations survived much later than the 10- to 12,000 years ago commonly given as their extinction date. There were still mammoths alive in the world only 4,000 years ago and maybe only 3,700 years ago—but only on an island where humans didn’t live.

Wrangel Island is located in the Arctic Ocean near western Siberia, more than 85 miles from the nearest coast, or 140 km. It has low mountains and sea cliffs and is cold and dry most of the year, which is the kind of climate mammoths preferred.

The woolly mammoths that lived on Wrangel Island were probably cut off from the mainland when sea levels rose and flooded Beringia. They lived on for thousands of years after their mainland relations had gone extinct. Gradually the mammoths became more and more inbred, leading to genetic defects at a much higher rate than in a healthy population. Even so, the mammoths might have managed to survive even longer except for one thing. Around 1700 BCE, humans arrived on the island. Shortly afterwards, the mammoth was extinct.

Wrangel Island is a nature sanctuary these days and home to lots of animals, including polar bears, walruses, Arctic foxes, seals, reindeer, musk ox, and wolves. All of these are considered ice age megafauna, so although the mammoths are gone, other megafauna remain.

While we don’t know for sure that humans played a big part in the end-Pleistocene extinction event, we sure didn’t help. We can’t blame our ancient ancestors for their actions but we can learn from their mistakes. We’re in the middle of another extinction event right now, often called the Holocene extinction or Anthropocene extinction, directly due to our actions. Habitat loss, pollution, overhunting, and human-caused climate change are driving more species of animal and plant to extinction every year.

It can feel overwhelming, but there are lots of small things you can do to help. Just picking up trash and putting it in the waste bin or remembering to take your reusable bags to the grocery store can make a difference. No one person can fix all the world’s problems, but if everyone does a little bit to help, the big problems get smaller and more manageable. If everyone pitches in, we can make the world a cleaner, better place for animals and for people.

Happy new year! Let’s make it a great one!

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!