Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 10:37 — 11.0MB)

Yay, we’re at the end of the year and looking forward to 2023! Boo, I caught covid and I’m still recovering, so here’s a repurposed Patreon episode about whale strandings and how people help the whales!

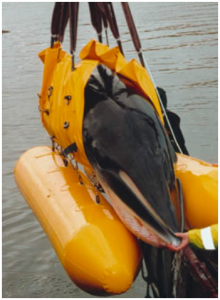

A minke whale calf being transferred via rescue pontoon to a boat to tow her farther out to sea than the pontoon could manage for such a big whale (photo from this article, which explains that she rejoined her mother and swam away safely):

Pilot whales being rescued after stranding:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast! I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

It’s the last episode of 2022, and…I’ve got Covid. I’m fully vaccinated and fortunate enough to be a basically healthy person, so my symptoms were mostly quite mild and I’m feeling much better although I’m still quarantining. Because my voice isn’t really at 100% due to coughing, and because I haven’t had the energy to do any research, I decided to run an old Patreon episode this week. I always feel bad for my awesome patrons when I do this, but I really like this episode and it’s several years old now. It’s about mass whale strandings but I focused on how people help whales, so even though it’s a sad topic I hope you find it hopeful and interesting.

With the end of 2022, we also say goodbye to the birthday shout-outs since it was only for 2022. I hope I didn’t miss anyone. Let’s have one final birthday shout-out, though. This one’s for everyone! You’re having a birthday in 2023 so I hope it’s the best birthday you’ll have had so far!

Now, let’s learn about mass whale strandings.

[little intro sound to help hide the fact that the audio changes a whole lot here]

This is a sad phenomenon where whales swim onto shore and get beached, and if they don’t get help they die. A whale breathes air, sure, but it’s evolved to be in the water full-time. As soon as it’s on land, the weight of its own body starts to smother it and it also starts to overheat.

Sometimes just one or two whales strand themselves, sometimes it’s a whole pod. We’re still not completely sure of the causes except that there’s undoubtedly more than one cause. Navy sonar may play a part, disorienting and frightening whales, even deafening them. Water pollution, disturbances of the earth’s geomagnetic field, extreme weather, injuries, disease, the whales fleeing predators or pursuing prey, and all sorts of other issues may be causes or partial causes.

Most whales that strand themselves are toothed whales, which rely on echolocation to navigate. Many researchers think that some coastlines that slope very gently can confuse the whales, who think the seafloor is level when the water is actually getting shallower and shallower. Certain areas with gently sloping beaches have mass strandings of whales and dolphins almost every year.

Some species of whale are more prone to stranding than others, too, especially pilot whales, which are actually dolphins despite their name. The largest mass stranding known was of pilot whales, with over a thousand of them beached in 1918 on Chatham Island in New Zealand. Pilot whales can grow more than 23 feet long, or over 7 meters, and live throughout much of the world’s oceans. They mostly eat squid but will eat fish too, and sometimes dive deeply to find food.

Chatham Island is one of those areas where whales get stranded repeatedly, as are several other islands and bays around New Zealand. The coastal waters are shallow with a number of sandbars, and the whales apparently get disoriented and don’t realize they’re coming up onto the beach instead of just crossing another sandbar. Almost every summer some pilot whales become stranded, sometimes hundreds of them.

One species of whale that almost never gets stranded is the killer whale, or orca. Orcas frequently hunt seals, which flee onto land. Orcas learn how to navigate beaches, and will sometimes beach themselves on purpose while attempting to catch a seal, then wriggle back into the sea. But most whales never approach the shore that closely under ordinary circumstances so they never learn how to avoid getting stranded permanently.

When people find stranded whales, our first impulse is to help them. But whales are big and heavy, so much so that most of the time even a group of people can’t lift them. But humans are smart and social, and we’ve worked out a system to help stranded whales.

First, the whales need to be kept as cool as possible until more help arrives. People pour water over stranded whales to help cool them down, but make sure that their blowholes remain clear of sand and water so they can continue to breathe. Wet bed sheets draped over the whales help too, again making sure to keep the blowholes clear.

Next, as the tide comes in and the water rises around the whales, it’s important to help turn the whales onto their bellies. The whales usually can’t do it themselves, especially if they’ve been stranded for hours and are exhausted and having difficulty breathing. If they aren’t turned upright, they may drown as the water covers their blowholes before it’s deep enough to float the whales.

Sometimes, frustratingly, as soon as a stranded whale is floated out to sea so it can swim away, it will turn around and beach itself again. No one’s sure why. It may be responding to the same confusion or anomaly that caused it to strand itself in the first place, or it may be responding to the distress calls of other whales that are still stranded.

Rescuers have used the sociability of whales to help them too. In one case in New Zealand, in 1984, almost 150 pilot whales became stranded in Tryphena Harbour. As the tide rose, the helpers floated the whales out to sea—but so many of them returned to beach themselves again that when they floated a mother whale and her calf out to sea, the rescuers made sure to keep her in place. She and the baby called to the other whales, which made them come to her instead of return to the beach. 67 of the whales were saved and ultimately swam out to sea.

In 1991, 14 pilot whales stranded near Shipwreck Bay in New Zealand were rescued by truck. The surf was too dangerous to refloat them at the beaching site and something had to be done. 18 whales had already died. Hundreds of volunteers turned out to help, including local businesses who donated the use of trucks and other items. The whales were lifted by log-loader onto three big trucks, their beds lined with hay, and hay bales were used to keep the whales propped up during the ride. People rode with them to douse them with water too. The police escorted the trucks as they drove 90 minutes to the mouth of a river, where the whales were lowered into the water and floated out to sea.

Two of the whales promptly turned around and beached themselves again, but the volunteers had brought Rescue Pontoons designed to refloat beached whales. The two whales were brought back out to sea where they rejoined the rest of the rescued whales, which then swam off together.

The rescue pontoons were designed in 1984 by New Zealander Steve Whitehouse after he saw the damage ropes did to whales as rescuers tried to pull them back out to sea. They’re made up of inflatable cylinders with handles and quick release clips. After the first one was made it was tested by moving a huge concrete pipe filled with sandbags into the ocean and back repeatedly. It was first used to rescue a whale in 1986 when a Southern Bottlenose whale was stranded among rocks that would have kept it from being moved by ordinary means. But Steve and his team traveled to the whale, rolled it onto the pontoon and inflated it, then refloated it into the sea. The whale was saved and the rescue pontoon proved it could do the job it was designed for.

Since then, the rescue pontoon has saved hundreds, probably thousands, of whales and dolphins throughout the world. It’s also been used to rescue stranded manta rays, sunfish, and even grounded boats. So hooray for Steve and his rescue pontoon! Best invention ever.

Humans aren’t the only ones who want to help stranded whales. Sometimes other whales or dolphins help, usually local populations of dolphins who know the area well. In 2008 a New Zealand bottlenose dolphin named Moko, well-known to swimmers, helped a pair of pygmy sperm whales. The pair were a mother and calf, and every time they were refloated they would get disoriented and beach themselves again on a sandbar that blocked their way out of the harbor. Then Moko showed up.

One of the rescuers, Juanita Symes, said, “Moko just came flying through the water and pushed in between us and the whales. She got them to head toward the hill, where the channel is.” Moko escorted the whales all the way out to sea, where they successfully swam away.

[little outro sound]

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!