Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 14:27 — 15.0MB)

We have a merch store now too!

Thanks to Ethan for this week’s topic, two weird animals that developed after the Great Dying we talked about last week!

Further reading:

Monkey Lizards of the Triassic

Placodonts: The Bizarre ‘Walrus-Turtles’ of the Triassic

Drepanosaurus (without a head since we haven’t found a skull yet, but with that massive front claw):

Drepanosaurus’s tail claw:

Hypuronector had a leaf-like tail:

Placodus was a big round-bodied swimmer:

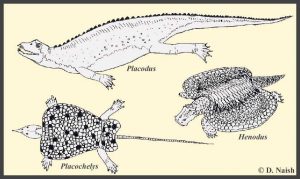

Some placodonts [art by Darren Naish, found at the second article linked above]:

Henodus was the oddball placodont that probably ate plant material:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

Last week we talked about the end-Permian mass extinction, also called the Great Dying. This week let’s follow up with a couple of weird and interesting animals that evolved once things got back to normal on Earth. Thanks to Ethan who suggested both animals.

The great dying marks the end of the Permian and the beginning of the Triassic period, which lasted from about 251 million years ago to 201 million years ago. In those 50 million years, life rebounded rapidly and many animals evolved that we’re familiar with today. But some animals from the Triassic are ones you’ve probably never heard of.

We’ll start with a reptile called the drepanosaur. Drepranosaurs are also sometimes called monkey lizards for reasons that will soon become clear. Paleontologists only discovered the first drepanosaur in 1980, Drepanosaurus, and within a few years they recognized a whole new family, Drepanosauridae, to fit that first discovery and subsequent closely related specimens. Drepanosaurs were weird little reptiles that probably looked like lizards in many ways, although they weren’t lizards.

How weird was Drepanosaurus? Very weird. Very, very weird.

It was obviously a climbing animal that probably spent all of its life in the treetops. It had lots of adaptations to life in trees, such as hind feet where all the toes pointed in the same direction and were somewhat curved, sort of like a spider monkey’s hand. That would help it get a good grip on branches. But those hind feet aren’t why it’s called the monkey lizard.

Drepanosaurus and its relatives are called monkey lizards because of their tails. Many monkeys have prehensile tails, which act as a fifth limb and help keep the monkey stable in a tree by curling around branches and hanging on. Drepanosaurus had something similar. Instead of being mobile from side to side like most reptile tails, Drepanosaurus’s tail could mostly only curve downward. Modern chameleons have an even more pronounced downward-curving tail that helps them climb. But the chameleon’s tail is still just a tail. The end of Drepanosaurus’s tail had several modified caudal bones that were probably exposed through the skin. Those modified bones acted as a claw to help the animal grab onto tree trunks and branches. So Drepanosaurus had claws on its front feet, claws on its hind feet, and a claw on its tail. It’s sort of like having five feet.

As if that wasn’t weird enough, let’s talk about those claws on the front feet. It had five toes on each foot, and four of them had ordinary claws. They were sharp but fairly small, about what you’d expect from an animal that grew about 19 inches long at most, or 50 cm. But the second toe on each foot, which corresponds to the pointer finger on a human hand, had a much bigger claw. MUCH BIGGER CLAW. It was as big as its whole hand! Most researchers think it used the claw to dig into rotting wood, insect nests, and bark to find insects and other small animals to eat.

But that’s not all. Drepanosaurus also had a structure called a supraneural bone at the base of its neck, made up of fused vertebrae, that would have made it look like it had a little hunch on its shoulders. While we don’t have a skull of Drepanosaurus, since we only have three specimens so far, this structure is also present in other drepanosaur species where we do have the neck and head, and they all have fairly long, slender necks and birdlike skulls with large eyes. It’s possible that the supraneural bone was the attachment site for special muscles that helped Drepanosaurus extend its neck very quickly to grab insects and other small animals.

Drepanosaurs in general shared many of the traits seen in Drepanosaurus, although with some differences. Many drepanosaurs had opposing toes on the feet that would help them grasp branches and twigs more securely. Most don’t have the giant claw on the front feet although most do have the tail claw. But one monkey lizard doesn’t live up to its name at all.

A little drepanosaur called Hypuronector limnaios, which only grew about five inches long, or 12 cm, had a much different tail from its relations. Its tail didn’t curve downward at all—in fact, it stuck up behind it and was probably not very flexible. Not only was the tail longer than the body and head together, it had long points growing down from the vertebrae, called haemal arches, which made the tail extremely large top to bottom but flattened from side to side.

In other words, its tail looked like a leaf. The drepanosaur could cling to a branch with its tail sticking up, and any nearby predators would probably think it was just another leaf growing from the branch, especially if the tail was covered in green skin. Some researchers speculate that it could have used its tail as a sail to glide from branch to branch too, or it might have acted as a parachute if it had to jump from a branch to escape a predator. Hypuronector’s front legs were longer than its hind legs, unlike other drepanosaurs, which suggests it might have had a flap of skin that helped it glide.

Drepanosaur fossils have been found in parts of the United States and western Europe, but were probably more widespread than that. We still don’t know a whole lot about them, so every new specimen that’s found can give paleontologists lots of new information. Most drepanosaurs resembled weird chameleons with birdlike heads, but they weren’t related to birds or chameleons. We don’t actually know what they were closely related to.

Ethan also suggested placodonts, another reptile that evolved in the Triassic. Don’t confuse them with placoderms, the armored fish that went extinct in the great dying. The “placo” part of both words means tablet or plate. Therefore, placoderms have skin—that’s the “derm” part—covered in plates, while placodonts have flattened teeth, because the “dont” part refers to teeth. That’s why you get braces on your teeth at the orthodontist but you go to the dermatologist for skin problems.

What did placodonts do with their flattened teeth? They used them to crush the shells of shellfish and crustaceans. From that you can infer that they were marine reptiles, and you would be right. The earlier species had big round bodies with heavy bones, which helped them dive to the ocean floor to find food. They lived in shallow coastal waters and had large flattened ribs that helped protect them from injury if currents pushed them into rocks. While the teeth in the back of the mouth were flattened to crush shells, the teeth in the very front of the mouth were sharp and pointed forward to grab prey.

One of the most common early placodonts was Placodus [PLAK-oh-dus], which grew nearly six and a half feet long, or 2 meters. Its long tail was flattened laterally to help it swim and it probably had webbed toes. Since its legs were small and relatively weak considering how heavy its body was, it probably couldn’t get around very well on land, so it would have stayed close to the water. It probably looked kind of like the modern marine iguana, which we talked about in episode 92, but with longer jaws. On the other hand, unlike the marine iguana, placodus had a third eye.

THIRD EYE ALERT! If you remember way back in episode 3, where we talked about the tuatara, we learned a little bit about the parietal eye, or third eye. Parietal eyes are found on the top of a few animals’ heads, including the tuatara, but they aren’t the same as ordinary eyes. They’re very small photoreceptive eyes that can only sense light and dark. In Placodus’s case, researchers think that ability helped it figure out which way was up more easily when it was underwater. If you’ve ever been knocked down by a wave you’ll understand how easy it is to get disoriented underwater.

Placodus and other early placodonts had a ridge of bony scutes on the back to help protect it from predators. In later placodonts those scutes were bigger and bigger until they were more like armor, which added weight to the body and meant that the bones didn’t have to be so dense. This meant that instead of having barrel-like bodies, later placodonts were a little more streamlined. Their bodies were more flattened than round, but still broad across with big plates protecting the back. Their legs were more like flippers.

Does this make you think of something? Something like a sea turtle?

Later placodonts looked a lot like turtles, a classic case of convergent evolution because they weren’t related to turtles at all. If you saw Placochelys, for instance, you’d probably just think it was a weird sea turtle, unless you got a really close look at it. It grew about three feet long, or 90 cm, with a triangular head, a knobby shell, and flippers with clawed toes at the ends. It had a beak like a turtle’s instead of Placodus’s forward-pointing teeth, but unlike a turtle it also had teeth in the back of the mouth. These were still big flat teeth used for crushing shellfish, but like other placodonts the upper teeth grew from the palate, or the roof of the mouth.

Other placodonts would have looked strange to us, like Psephoderma. It grew up to six feet long, or 180 cm, and instead of a single turtle shell, it had two shells. One covered its body from the back of the head down to the pelvis. The other covered its pelvis and was smaller. It had a long tail and a pointy nose.

At least one placodont didn’t live in the ocean and didn’t eat shellfish and crustaceans. Henodus grew about three feet long, or one meter, and lived in brackish water or possibly freshwater. Its shell was twice as broad as it was long. It also had a lower shell, or plastron, on its belly. Its nose was short and squared-off and it had a turtle-like beak, and instead of teeth it had denticles on the sides of its jaws. Some researchers think it was a filter feeder, filtering tiny animals from the water through the denticles, while other researchers think it may have eaten water plants. It might have done both.

There’s a lot we don’t know about placodonts. We don’t know if they laid eggs or gave birth to live young, and we don’t know what exactly they ate. Obviously their teeth were best suited to crushing shells, but we don’t actually know what kind of shellfish they preferred or if they only ate crustaceans or something else. Placodont remains have been found in Europe, the Middle East, and China, but they were probably more widespread than that. During the Triassic, as the supercontinent Pangaea broke up, it created lots of shallow oceans and island chains that would have been ideal for placodonts.

Unfortunately for the placodonts, as the landmasses moved farther apart over millions of years, the shallow seas became deeper. Populations would have become isolated from each other. Eventually placodonts went extinct, probably by a combination of habitat loss and competition from other animals as dinosaurs and their relatives spread throughout the world.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us that way, and don’t forget to join our mailing list. There’s a link in the show notes.

Thanks for listening!