Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 20:33 — 15.6MB)

Thanks to Kristie and Jason, we’re going to learn about some mystery big cats reported in Australia, in particular Victoria.

Further reading:

Official big cat hunt declared a bust, so why do people keep seeing them?

Further watching:

Thylacine video from 1933, colorized

You’ll probably need to enlarge this but it’s a still from a 2018 video purportedly showing a mystery big cat, but in this frame you can see the ears are pointy, which is a sure sign of a domestic cat:

A melanistic (black) leopard and regular leopards (picture from this site). If you zoom in you can see the spot pattern on the black leopard:

A puma/cougar/mountain lion. Note the lack of spots:

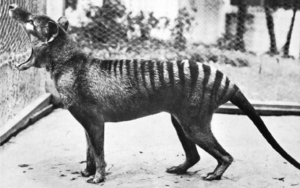

A thylacine. Note the lack of spots but presence of stripes:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week is Kristie and Jason’s episode. They want everyone to learn about mysterious big cats in Australia!

Australia, of course, is home to many wonderful animals, but almost all of the native mammals are marsupials. There are no native felids of any kind in Australia, even in the fossil record. This is because Australia split off from the rest of the world’s landmasses when the supercontinent Gondwana broke apart. Marsupials actually first arose in South America and spread to Australia when the two landmasses were connected. Then, around 180 million years ago, South America and Africa split off from the rest of Gondwana, including Australia. Most of South America’s marsupials went extinct as placental mammals arose and became more and more numerous, but Australia was on its own starting about 30 to 50 million years ago. Marsupials never had to compete with placental mammals during most of that time, except for bats, and the marsupials thrived.

Humans first populated Australia at least 41,000 years ago and probably more like 65,000 years ago. The first dingoes, a type of dog, were introduced around 5,000 years ago. The first European sighting of Australia was in 1606, and less than 200 years later the British colonized the continent, bringing with them invasive species like cats, rats, cattle, sheep, foxes, rabbits, deer, and lots more, which have driven many indigenous animals to extinction. But while domestic cats are common in Australia, as far as we know no one has ever deliberately released enough big cats to form a breeding population.

In that case, though, why are there so many reports of big cats in parts of Australia?

If you remember way back in episode 52, where we talked about big cats in Britain, there were lots of stories and a certain amount of evidence that individual big cats were occasionally found in the country. Ultimately, though, there’s no proof of a breeding population of big cats. The same is more or less true in Australia, but Australia is so much bigger and so much less populated than Britain, it would be easy for a small population of big cats to hide. And maybe they’re not actually big cats but some other animal, something that is native to Australia.

Kristie and Jason have lots of experience searching for big cats in central Victoria, Australia. They even helped with the research of a book about big cat sightings. Victoria is in southeastern Australia and is the smallest state. If you walked south from central Victoria to the coast, and then got on a boat and kept going south, you’d run into Tasmania. If you walked north instead, eventually you’d come to New South Wales but that is going to be a long walk. Victoria is mostly temperate and rainy but has tall mountains, semi-arid plains, and lots of rivers.

As Kristie pointed out, different parts of Australia have different stories about mystery big cats, but I’m mostly going to talk about sightings in Victoria, just to narrow it down.

To start us off, now that we have some background information, here’s a clip from the conversation I had with Kristie. The audio isn’t great, unfortunately, but it’s definitely interesting.

[quote of Kristie’s account:]

“Jason and I used to go puma hunting. It was very scary. So, there was this bloke we used to go and visit. I’m not going to name any names; I’m not even going to tell you exactly where he was other than he was in Castlemaine along a railway line, a disused railway line. So, the story goes that this man (let’s just take 80% of what he says with a grain of salt), he’d gone up to get a horse from a paddock outside their house that they lived in, on a dirt road near the railway. There was lots of long grass on the side of the road. He said he went to get the horse and was bringing the horse back to the house paddock, and he felt like he was being watched. Not a good feeling. And then he heard something that sounded like a growl coming from in the grass. And the horse had a bit of a moment. He continued on his way—he was safe, the horse was safe! No animals were hurt in the making of this story. From then on he said he and his wife would hear things walking around their house and it would just feel really weird. They would say that they actually saw these cats walking along the road.

“I would call Jason and we’d get on a motorbike and we’d go down, probably about a 5 or 10 minutes motorbike ride. Of course whenever we got there, there was nothing there. Occasionally you might see something on the dirt road, because there was a bit of fine dirt on there that maybe you could find a footprint on there.

“You would hear dogs bark, hear them off in the distance when whatever it was out there was on the move. It would actually follow the creek down and the railway line and you would get a succession of dog barks.”

Kristie went on to say that they’d even found and taken a plaster cast of a large paw print that looked different from a dog’s print, but the veterinarian they took it to wasn’t able to determine whether it was made by a big cat or just a dog.

She also talked about some other evidence that their friend gave as proof of big cats living in his paddock, including swirls in the long grass that looked like a cat had flattened the grass to sleep. In that case, she also pointed out that the same thing had happened in her own yard recently and that she was pretty sure it was caused by the wind. But here’s another clip from her about an experience she had that wasn’t so easy to explain:

[quote of Kristie’s account:]

“I spent one night out in a caravan that they had in their yard, just waiting, and I heard a cough. Pumas cough, but so do kangaroos, so I don’t know. I didn’t see any kangaroos. I like to think I heard a puma cough. I honestly don’t know what I heard.”

Kristie even thinks she spotted a big cat once as she and Jason rode by on a motorbike, but by the time she realized what she’d seen, it was long gone. She said it was a large black animal with a very long tail, much longer than a domestic cat’s tail.

One theory of big cat sightings is that they’re descendants of cougars, also called pumas or mountain lions, brought to Australia as mascots by American troops during World War II but released into the wild. While WWII units from various countries did often have mascots, they were usually dogs. A few mascots were domestic cats, there were a couple of pigs, birds, and donkeys, but mascots were almost always domesticated animals that a unit adopted even though they weren’t really supposed to have them. Wild animals were rare as mascots because they were hard to handle and hard to hide from officers. While there were certainly some big cats of various kinds brought to Australia by American soldiers and released when they started getting too big and dangerous to handle, or when they were found by officers, there wouldn’t have been enough to form a breeding population.

Besides, big cat sightings go back much earlier than the 1940s. Some people blame Americans again for these earlier stories, specifically American miners who came to Australia in the mid-19th century gold rush. Supposedly they brought pet cougars that either escaped or were released into the mountains. While miners did bring animals, they were almost always dogs or pack animals like mules.

More likely, though, any big cats escaped or released into the Australian bush in the olden days came from traveling circuses or exotic animal dealers. Even so, again, there just weren’t enough big cats of any given species to result in a breeding population. But, also again, people are definitely seeing something.

The most compelling evidence for big cats in Australia is attacks on large animals like horses, cattle, calves, and sheep. Australia doesn’t have very many large predators. Dingoes are rare or unknown in Victoria these days, as are feral pigs, foxes don’t typically hunt animals larger than a rabbit or chicken, and feral dogs usually leave telltale signs when they attack livestock.

In 2012, the Victorian Department of Sustainability and Environment commissioned a study of big cat sightings in the state. The study’s aim was to determine whether a breeding population of big cats might exist, and if so, what impact it was having on the native wildlife. The team examined historical and contemporary reports of big cats, and studied photos and videos and other evidence. Its findings were inconclusive—there just isn’t enough evidence that big cats are living in Victoria, although it couldn’t rule it out either—and it recommended further investigation.

An earlier study in the 1970s by Deakin University also attempted to determine whether big cats lived in the Grampians, a national park that includes a mountain range. Its traditional name is Geriwerd. The study came to the conclusion that there probably were pumas in the Grampians, but one of the pieces of proof, a 3-inch, or 8-cm, fecal pellet, was later identified as a pellet regurgitated by a wedge-tailed eagle.

Kristie also mentioned that the wedge-tailed eagle might be the source of some claw marks found on wildlife. The wedge-tailed eagle is a large, robust bird with a wingspan over nine feet across, or 2.84 meters, and it lives throughout Australia and southern New Guinea. It’s mostly black or brown in color and has a large hooked bill and large, strong talons. It often hunts in pairs or even groups and can kill animals as large as kangaroos. Larger species of wallabies and other native animals are the eagle’s natural prey but it also eats lots of introduced animals like rabbits and foxes, and occasionally kills lambs or piglets. It also eats a lot of carrion.

Eagle attacks don’t explain everything, though, such as claw marks found on horse rugs. Horse rugs are special blankets that horses wear, especially in cold weather. There are also reports of dead sheep and goats found dragged into trees or through fences, something a dog couldn’t or wouldn’t do but a leopard or other big cat could.

In 1991 a piece of poop, more properly called scat or feces, was turned into authorities and sent for testing. Initially reports said it looked like it came from a large felid, although what species couldn’t be determined. Fortunately it was saved and was genetically examined a decade or so later, at which point it matched up to a leopard. Assuming it was actually found in the bush and wasn’t a joke by an exotic pet owner, it means there was a leopard running around in central Victoria a few decades ago for sure.

Most sightings of Australian big cats fall into two categories: black cats and tan or gray-brown cats with white bellies. As we learned in last year’s wampus cat episode, the cougar is tan or gray-brown in color, sometimes called yellowish, with a pale belly, but is never black. Melanism is common in some big cats, especially leopards and jaguars, but leopards and jaguars are always spotted. Even melanistic individuals show a faint spotted pattern up close. So if some Australian big cats are black and other Australian big cats are tan or gray-brown without spots, they’re probably not the same species. But now it’s even more complicated! How could there be two species of big cat hiding so close to people without anyone hitting one with a car or shooting one in a pasture or just getting a really good picture of one on a trail cam or just a phone?

A lot of people think that feral domestic cats are responsible for all the sightings. While some feral cats can grow larger than average for a domestic cat, especially in areas where there’s lots to eat, most are actually quite small and thin. Feral cats are definitely responsible for a lot of big cat sightings, but not all. Black domestic cats in particular stand out in fields and on bright days so might be noticed more often than other colors of cat, and it’s easy to see a big black cat in the distance, not very close to anything, and assume it’s larger than it really is. But pictures and videos of these cats are usually pretty easy to identify as domestic. Domestic cats have pointy ears set high on the head, unlike big cats who have rounded ears that are lower on the head.

One video from 2018 is often cited as proof of a big cat in Australia, although in this case it’s in New South Wales. If you check the show notes, you’ll see a still I took from the video showing the animal’s ears. They’re pointy ears so the animal has to be a domestic cat.

There’s always another possibility, of course. Maybe the big cats aren’t cats at all but rare, reclusive carnivorous marsupials. The two main contenders are the marsupial lion and the thylacine.

The marsupial lion, or Thylacoleo carnifex, isn’t actually a lion. It’s a marsupial, and in fact I should say it was a marsupial because it went extinct at least 30,000 years ago as far as we know. It was probably almost as big as a lion, though, with massive jaws and teeth that could bite through bones. It ate large animals like the giant wombat relation Diprotodon and giant kangaroos, so it would have no trouble with a sheep.

But the marsupial lion didn’t actually look like a lion either. It probably resembled a small bear in some ways, although it had a thick tail more like a kangaroo’s than a cat’s. Its method of hunting doesn’t match up with the dead animals found in Victoria either. The marsupial lion had huge claws that it used to disembowel its enemies, I mean its prey, whereas modern big cats mostly use their strong jaws to bite an animal’s neck. Also, of course, the marsupial lion went extinct a really long time ago. While there’s always a slim possibility that it’s still hanging on in remote areas, I wouldn’t place any bets on it. I don’t think it’s the real identity of the mystery big cats. There are just too many discrepancies.

The thylacine, also called the Tasmanian tiger because it lived in Tasmania and had stripes, was about the height of a big dog but much longer. It was yellowish-brown with black stripes on the back half of its body and its tail. It had relatively short legs but a very long body and its tail was thick. It was a carnivorous marsupial, mostly nocturnal.

The thylacine went extinct in mainland Australia around 3,000 years ago while the Tasmanian population was driven to extinction by white settlers in the early 20th century. But like big cat sightings, people still report seeing thylacines. Maybe people are mistaking thylacines for big cats, since a quick glimpse of a big tawny animal with a long tail could resemble a puma if the witness didn’t see its stripes or didn’t notice them in brush or shadows.

The thylacine wasn’t a very strong hunter, though, at least as far as researchers can tell. But there’s a lot we don’t know about the thylacine even though it was still alive less than 100 years ago. As Kristie says:

“Maybe it was a thylacine. Who knows?”

Kristie and Jason think most big cat sightings are explainable as feral cats and other known animals. They also pointed out that what appear to be unusual predation methods might just be caused by more than one kind of animal scavenging an already dead carcass.

But there are lots of sightings that can’t be explained away, and people occasionally find dead animals that look like they’ve been killed and eaten by a big cat instead of a dog or eagle. While there’s a low probability that a breeding population of big cats is living in Victoria, there’s a very good chance that a few individual animals are. They’re most likely escaped or released exotic pets, possibly ones that were kept illegally in the first place.

As Kristie and Jason point out, people often freak out when they’re confronted with something strange, like the possibility that a leopard is sneaking around their house. You can’t really blame them. That’s why it’s so important to find out more about these animals, because turning the unknown into the known helps people know what to do and not be so scared.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!