Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 14:18 — 14.5MB)

Re-recorded after two years, yesss! Episode one now has decent audio quality and has been slightly updated to reflect new findings about the thylacine.

The Thylacine (commonly called the Tasmanian tiger) and the quagga, a type of zebra, have two important things in common. They’re both partially striped and they’re both extinct. Sort of. The first episode of Strange Animals Podcast discusses what sort of animals both were, and why we can’t say with 100% certainty that they’re extinct. Even though we know the date the last individuals died.

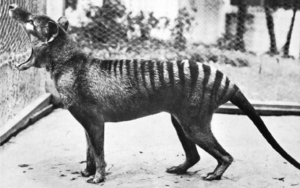

The Thylacine. Look at those jaws! How does it open its mouth that wide?

Watch the 2008 thylacine (maybe) video for yourself.

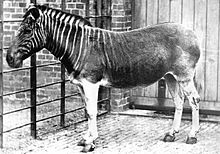

The Quagga, old and new:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

If you’re wondering why episode one is suddenly appearing in your feed after more than two years, it’s because I’ve rerecorded it. Quite often people who are interested in a podcast download the first episode to check it out, and our first episode sounded TERRIBLE. So here’s a fresh new version with a little bit of extra information included.

If you’re already a Strange Animals Podcast listener, I hope you don’t mind this redone episode showing up in your feed. Don’t worry, there will be a new episode next Monday as usual! If you’re a new listener, I hope you like the podcast and stick around!

The first episode of Strange Animals Podcast is about the thylacine and the quagga. Both animals are kinda-sorta extinct and both are partially striped. So they go together!

You may know the thylacine as the Tasmanian tiger or wolf, or you may be confused and think I’m talking about the Tasmanian devil. The Tasmanian devil is a different animal although it does live in the same part of the world.

The thylacine was a nocturnal marsupial native to Australia, New Guinea, and Tasmania, but it went extinct early in the 20th century. The last known individual died in captivity in 1936. But in 2008, footage of a long-tailed doglike animal was caught on film near Perth in Western Australia.

Thylacine sightings have been going on for years—basically ever since it was declared extinct. It was a shy, nervous animal that didn’t do well in captivity and sometimes died of shock when captured, so if the animal survives in remote areas of Australia or Tasmania, it’s obviously keeping a low profile.

The thylacine was as big as a good-sized dog, some two feet high at the shoulder, or 61 cm, and over six feet long if you included the tail, or 1.8 meters. It wasn’t very fast, seldom traveling faster than a stiff trot or an awkward canter. I’ve read accounts that it would sometimes hop instead of run when it needed to move faster, but this seems to be a myth. If thylacines are wandering around outside of Perth or anywhere else, it’s surprising no one has accidentally hit one with a car. The Tasmanian devil is in such steep decline that it’s projected to be extinct in the wild by 2024 at the latest, and in 2014 over 400 of them were killed by cars.

No other animal in Australia and Tasmania looks like the thylacine. It was yellowish-brown with black stripes on the back half of its body and ringing the length of its tail. Its head was heavy and doglike, with long jaws and erect, rounded ears. Its legs were relatively short while the body and especially the tail were long. It could open its jaws startlingly wide although it didn’t have a very strong bite. It was also a quiet animal, rarely making noise except while hunting, when it would give frequent double yips.

Not a lot is known of the thylacine in the wild. Tasmanian Aborigines would build little structures over thylacine bones, since letting the bones get rained on was supposed to bring on bad weather. I still love this so much.

The thylacine was killed by British colonists who thought it preyed on livestock, but it was actually a weak hunter that probably couldn’t kill prey much larger than a chicken. In fact, some researchers think the thylacine’s primary source of food was the native hen, and once that bird went extinct in the mid-19th century, thylacine numbers started to decline. It certainly didn’t help that bounties for dead adults were as much as a pound—big money in the 19th century. Captive animals were prone to a distemper-like disease and only one pair successfully bred in captivity.

So what about all those sightings? Is it possible that small populations of the thylacine survived loss of both habitat and prey animals, bounty hunting, and competition with introduced dingos? There have been numerous organized searches for signs of the thylacine, with nothing to show except blurry photos and grainy film footage. But we don’t have anything concrete: no bodies, no clear photos, not even any good footprints.

As for the 2008 video, the Thylacine Awareness Group of Australia released it in September of 2016, eight years after it was recorded. The person who took the footage states that she had seen the animal repeatedly over a matter of weeks, and had also seen a female with two pups. She says they were all striped and did not look anything like foxes.

The footage isn’t very clear, but it shows a foxlike animal with a long tail. The recording is too grainy to make out any markings. Certainly the animal doesn’t appear to have the vivid stripes seen in old photos taken before the thylacine went extinct.

To me, the animal in the footage looks a lot like a fox with an injured leg or paw, which makes its gait seem odd. Its legs are much too long for a thylacine, the body is too short, and the hocks are too far up the leg. As for the long tail, I’ve seen foxes with mange and the tails look just like this one’s.

There’s another issue against the survival of the thylacine too. According to a 2012 study conducted by Andrew Pask of the University of Connecticut, the thylacine had a very low genetic diversity to start with. Isolated breeding populations would further limit the gene pool and eventually lead to a population that couldn’t survive due to physical issues associated with inbreeding.

That study only sampled from 14 different skins and skeletons, so it’s possible the situation wasn’t as bad as its results suggest. On the other hand, the Tasmanian devil is another species with low genetic diversity, and its numbers are declining steeply despite conservation efforts.

Since this original episode one went live in February 2017, there’s been a more comprehensive DNA study of thylacines that changes what we know about their past. A September 2017 study conducted by the University of Adelaide generated 51 DNA sequences from thylacine fossils and museum specimens.

The study discovered that the thylacine population split into two around 25,000 years ago, with the two groups living in eastern and western Australia. Around 4,000 years ago, climate change caused more and longer droughts in eastern Australia and the thylacine population there went extinct. By 3,000 years ago, all the mainland thylacines had gone extinct, leaving just the Tasmanian population. The Tasmanian thylacines underwent a population crash around the same time that the mainland Australia populations went extinct—but the Tasmanian population had recovered and was actually increasing when Europeans showed up and started shooting them.

It would be fantastic if a population of thylacines was discovered still alive somewhere. But it doesn’t look good right now. On the other hand, you can still see the Tasmanian devil. Just please try not to run over one. There aren’t many left.

[goat call, because why not]

When I was maybe twelve years old I read about the quagga for the first time, probably in a library book about animals. I remember being so moved at the thought of this fascinating zebra driven to extinction that I wrote a poem about it. Unfortunately for all of us, I remember the first two lines of the poem. Yes, I’m going to recite it again. I’m sorry.

“Dear quagga, once running

O’er field and o’er plain…”

It went on and on for two entire pages of notebook paper. Thank goodness I don’t remember any more of it.

Ever since that awful, awful poem, I’ve had a soft spot for the quagga. It really was an interesting-looking creature. The head and forequarters were striped and clearly those of a zebra, but if you were to see only its hindquarters you’d swear you were looking at a regular old donkey.

The quagga was a subspecies of plains zebra, and was common in south Africa until white settlers decided they didn’t want any wild animals eating up their cattle’s grass. By 1878 the quagga was extinct in the wild; the last captive individual died in 1883. Thanks a bunch, white settlers. You made twelve-year-old me cry, and I didn’t even know about Apartheid yet.

Locals in some areas still refer to all zebras as quaggas, supposedly as an imitation of the zebra’s call. I don’t know what variety of zebra this call is from, but I’m going to guess that all zebras kind of sound the same.

[zebra call]

That really is awesome.

It’s interesting to note that still-living plains zebras show less and less striping the farther south they live. The quagga lived in the southernmost tip of Africa, south of the Orange River in South Africa’s Western Cape region, an even more southerly range than the plains zebra’s. And as a reminder, the quagga was a subspecies of the plains zebra—so closely related that it’s sometimes impossible to tell stuffed specimens of the two varieties apart. Where their ranges overlapped, researchers think plains zebras and quaggas frequently interbred.

You can see where this is going, I hope.

In 1987, the Quagga Project in South Africa started with 19 plains zebras that showed reduced striping and had genetic markers most like quaggas. After five generations of selective breeding, the project has produced six foals as of 2016 that look like the extinct quaggas. The project calls them Rau Quaggas after Reinhold Rau, the project’s founder. Rau was inspired by the work of Lutz Heck, who was the guy responsible for breeding the heck horse to imitate the extinct tarpan. If you want to know more about the tarpan and the heck horse, check out episode 47 about mystery horses.

Eventually the group hopes to have 50 Rau quaggas that will live as a herd on reserve land in South Africa. Eric Harley, a genetics professor at Cape Town University and one of the founding members of the project, points out that while the Rau quagga isn’t an exact genetic match for the extinct quagga, it’s pretty darn close.

Of course there are people who criticize the group’s efforts for various reasons. Some say that since it’s impossible to reproduce the extinct quagga exactly, there’s no point in even trying. Others say that the resources spent trying to reproduce the quagga should be spent on conserving endangered animals instead.

But the Quagga Project is actually doing something useful for South Africa: working to reintroduce a type of zebra adapted to the colder environment, which can live in groups with ostriches and other animals that typically herd with zebras. When the Dutch exterminated the quagga, they messed up the balance of species in the area. Whether or not you think the Rau quaggas are analogous to actual quaggas, they’re going to be a good addition to the wildlife preserve.

And look, here’s the thing. Everyone gets to participate in the project they love, whether or not someone else thinks that project is worth it. We all have limited time in this world. One person wants to spend their energy recreating the quagga in South Africa, another wants to set trail cams up in Tasmania to look for thylacines, and a third person might happen to want to record a podcast about those people instead of washing the dishes. And that is OKAY.

Do what you love.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a Facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!