Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 11:03 — 11.1MB)

We have a fun mystery bird this week, the forest raven! Was it a real bird??? (hint: yes, but not a raven)

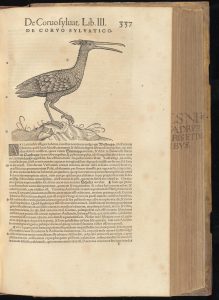

The “forest raven” illustration from Swiss naturalist Conrad Gessner’s Historiae Animalium, published in 1555:

Scans of the original pages about the forest raven. It’s written in Latin:

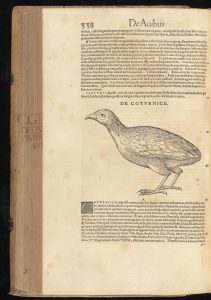

The Northern bald ibis. Wacky hair!

Flying bald ibises:

Further viewing:

This Weird Bird May Have Been the First Protected Species

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

It’s high time we had a mystery animal episode, so this week we’re going to learn about a mystery bird, one with a satisfying conclusion.

The story starts almost 470 years ago, when a scholar and physician named Conrad Gessner, who lived in Switzerland, published a book called Historia animalium. The book wasn’t like the medieval bestiaries of previous centuries, in which fantastical and real animals were listed together and half the information consisted of local superstitions. Gessner was an early naturalist, a scientist long before the term was in general use. Historia animalium consisted of five volumes with a total of more than 4,500 pages, and in it Gessner attempted to describe every single animal in the world, drawing from classical sources such as Pliny the Elder and Aristotle as well as his own observations and study.

The book contained animals that had only recently been discovered by Europeans at the time, including animals from the Americas and the East Indies. It also included a few entries which no one today believes ever existed, like the fish-like sea monk and sea bishop. Those and similar monsters were probably added by Gessner’s publishers against his will or maybe just without him knowing, since he was seriously ill by the time the volume on fish was published. For the most part, the book was as scholarly as was possible in the mid-16th century and was lavishly illustrated too.

Volume three, about birds, was published in 1555, and it included an entry for a bird Gessner called the waldrapp, or forest raven. But the illustration didn’t look anything like a raven. The bird has a relatively long neck, a crest of feathers on the back of its head, and a really long bill that ends in a little hook. Gessner wrote that the bird was found in Switzerland and was good to eat.

In fact, I spent an entire morning finding the original scanned pages of a copy of the forest raven entry, typing them as well as I could and modernizing the spelling where I knew how, and using Google translate from Latin to English. The results were…not entirely coherent. Then, after I’d done all that, I continued my research, and that included watching a short BBC film about the bird–which included part of the translation! So I transcribed it. Here’s a translation cobbled together from the BBC’s translation and other parts of the passage that me and Google translate could figure out:

“The bird is generally called by our people the Waldrapp, or forest raven, because it lives in uninhabited woods where it nests in high cliffs or old ruined towers in castles. Men sometimes rob the nests by hanging from ropes. It acquires a bald head in its age. It is the size of a hen, quite black from a distance, but if you look at it close, especially in the sun, you will consider it mixed with green. The Swiss forest raven has the body of a crane, long legs, and a thick red bill, slightly curved and six inches long. Its legs and feet are longer than those of a chicken. Its tail is short, it has long feathers at the back of its head, and the bill is red. The bill is suited for poking in the ground to extract worms and beetles which hide themselves in such places. It flies very high and lays two or three eggs. The young ones are also praised as an article of food and are considered a great delicacy, for they have lovely flesh and soft bones. Those who rob the nests of young take care to leave one chick so the parents will return the following year.”

All that sounds like a perfectly ordinary bird, although not a raven. But what was it? That’s the problem. No one knew, and eventually scholars decided that Gessner must have included a bird that didn’t exist.

But it did sound like one particular bird, just not one related in any way to the raven and not one that lived in Switzerland or other parts of Europe. That’s the northern bald ibis, which was once common across the Middle East and northern Africa.

Here’s a description of the Northern bald ibis. Let’s see how it matches up with Gessner’s forest raven.

The Northern bald ibis is a fairly large bird, about a foot long, or 31 cm, with a wingspan of four and a half feet, or 135 cm. That’s about the size of a goose. It has black feathers that shine with iridescent colors in sunlight, including bronze, violet, and green. It has long, dull red legs and a long, curved bill that’s also reddish. Its head is the same shade of dull red and has no feathers, but it does have a crest of long feathers on the back of its head and neck. It nests on cliff ledges and prefers to hunt for food in areas where the grass or other vegetation is short, such as pastures, fallow fields, semi-arid steppes, and golf courses, often ten miles or more from the cliffs where it nests, or 15 km. It eats insects and other small invertebrates, but it especially likes lizards and beetles. It probes into soft, sandy soil with its bill to find most of its food. The birds live in small flocks and often fly in a V formation.

The northern bald ibis mates for life. The male finds a good nesting site and tidies it up, then waits to see if he can attract a female. The female inspects the site and the male to decide if she likes them, and if she does, the pair build a nest of twigs lined with grass, and the female lays two to four eggs.

Oh, and the northern bald ibis is sometimes also called the waldrapp, just as Gessner reported.

All this information certainly sounds like the same bird Gessner described. But the northern bald ibis doesn’t live in Switzerland or other parts of Europe. It’s only known from the Middle East and northern Africa. Right?

That’s what people after Gessner thought, until 1941. That’s when a team of scientists excavating ancient sites in Switzerland found the bones of what turned out to be northern bald ibises—but the bones weren’t fossilized. They were only a few hundred years old. More remains, both fossil and subfossil, have since been found in France, Germany, Austria, and Spain, and the bird probably lived in even more areas.

It turns out that the northern bald ibis was once common in many parts of Europe, especially around the Alps. It was considered a sacred bird in ancient Egypt, and was supposed to be one of the birds released by Noah during the great flood to help him find land, so was venerated by people of different faiths in the Middle East. But in Europe, it was just considered good to eat. The Archibishop Leonard of Salzburg called for its protection in the Swiss Alps as long ago as 1504, but by the early 17th century, only a matter of decades after Gessner’s book was published, the bird was extinct in Europe. It didn’t take long for Europeans to forget it even existed.

Unfortunately, the northern bald ibis is still endangered due to hunting, habitat loss, and poisoning from pesticides. It’s also sometimes electrocuted when it lands on electricity pylons that aren’t insulated for birds, although efforts are underway to make pylons bird-safe in many areas. A successful captive breeding program has been in place since the late 1970s, though, and that’s a good thing, since the last migratory population went extinct in 1989 and the remaining non-migratory colonies declined to only a few hundred individuals.

The breeding program has gone so well that birds started being reintroduced in some areas of their former range in about 2003, including Spain, Germany, Austria, and Italy. Tagging of the remaining wild birds has also revealed that a small population still migrates from the Middle East to Africa to winter in central Ethiopia. In some areas, conservationists have added nesting platforms to the existing cliffs so that more birds can nest safely. Hopefully their numbers will continue to climb.

I’ll finish with a final piece of trivia about the northern bald ibis that I think you’ll like. It’s a member of the pelican family. Have a nice day.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or wherever you listen to podcasts. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!