Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 16:50 — 17.3MB)

Subscribe: | More

Thanks to Phoebe for suggesting the quokka and the wombat, two of the cutest, happiest-looking animals in Australia!

Further Reading:

Viral stories of wombats sheltering other animals from the bushfires aren’t entirely true

Satellites reveal the underground lifestyle of wombats

Giant Wombat-Like Marsupials Roamed Australia 25 Million Years Ago

Further Listening:

Animals and Ultraviolet Light (unlocked Patreon episode)

The adorable quokka with a nummy leaf and a joey in her pouch:

Quokka (left) and my chonky cat Dracula (right)

Some quokka selfies showing quokka smiles. That second picture really shows how small the quokka actually is:

Wombats!

A wombat and its burrow entrance:

A wombat mom with her joey peeking out of the rear-facing pouch:

Golden wombats. All they need is some Doublemint Gum:

Two (dead, stuffed) wombats glowing under ultraviolet light:

Show Transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to look at two super-cute animals from Australia, both of them suggestions by Phoebe. Thank you, Phoebe!

Let’s start with the quokka. It’s a marsupial, which as you may recall means that it’s a mammal that gives birth to babies that aren’t fully formed yet, and the babies then finish developing in the mother’s pouch. It’s related to kangaroos and wallabies but is quite small, around the size of an ordinary domestic cat. It’s kind of a chonk, though, which means it’s probably closer in size to my big chonk cat Dracula. It’s shaped roughly like a little wallaby or kangaroo but with a smaller tail and with rounded ears, and it’s grey-brown in color.

You may have seen pictures of the quokka online, because the reason it’s considered so incredibly cute is because it looks like it’s smiling all the time. If you take a picture of a quokka’s face, it looks like it has a happy smile and that, of course, makes the people who look at it happy too. Those are real pictures, by the way. Because of the way its muzzle and mouth are shaped, the quokka really does look like it’s smiling.

This has caused some problems, unfortunately. People who want to take selfies with a quokka sometimes forget that they’re wild animals. While quokkas aren’t very aggressive and are curious animals who aren’t usually afraid of people, they can and will bite when frightened. The Nature Conservancy of Australia recommends that people who want to take a selfie with a quokka arrive early in the morning or late in the evening, since quokkas are mostly nocturnal, and that they let the quokkas approach them instead of following one around. Touching a quokka or giving it food or drink is strictly prohibited, since it’s a protected animal.

The quokka lives on a few small islands off the coast of western Australia and a few small forested areas on the mainland. The largest population lives on Rottnest Island, and in fact the island was named by a Dutch explorer who thought the quokkas were rats. It means rat’s nest. The island’s actual name was Wadjemup and it was a ceremonial area for the local Whadjuk Noongar people.

Only an estimated 14,000 quokkas live in the wild today, with most of those on Rottnest Island. It used to be much more widespread, but once white settlers arrived and introduced predators like dogs, cats, and foxes, its numbers started to decline. It’s also threatened by habitat loss. It reproduces slowly, since a female only raises one baby a year.

A baby quokka is born after only a month, but like other marsupial babies, called joeys, it’s just a little pink squidge when it’s born. It climbs into its mother’s pouch where it stays for the next six months. Once it’s old enough to leave her pouch, it still depends on her milk for a few more months. While she’s raising one baby, though, the mother has other babies still in her womb ready to be born but held in suspended animation. This means that if something happens to her joey and it dies, the mother can give birth to another baby very quickly.

The quokka is most active at night. It sleeps during most of the day, usually hidden in a type of prickly plant that helps keep predators from bothering it. It gets most of its water needs from the plants it eats, and while it mostly hops around like a teensy kangaroo, it can also climb trees.

The wombat is another adorable Australian marsupial. For some reason, I’ve talked about the wombat several times in Patreon episodes but have barely mentioned it in the main feed–but that’s about to change. Mostly because I am going to recycle a lot of the information from the Patreon episodes, but I’ve also added a lot of interesting new details.

The wombat mainly lives in southern and eastern Australia, including Tasmania. It looks a little like a cartoon bear, a little like a cartoon badger, and a little like a cartoon giant hamster. Perhaps you notice a theme here. It has short legs, no tail to speak of, and is about the size of a medium-sized dog but stockier, with a broad face and rounded ears. The female has a rear-facing pouch to keep dirt and debris from getting on her baby while digging. There are three species alive today.

The wombat is mostly nocturnal and sleeps in a burrow during the day, although it will come out during the day when it’s overcast. It eats grass and other plants. It can dig really well and some people in Australia consider it a pest because it digs under fences.

The wombat has a big round rump with tough skin reinforced with cartilage. If a dingo or other animal chases a wombat, it dives into a hole and blocks the hole with its rump. The predator can’t get a purchase on the tough hide and there’s no tail to grab. The wombat isn’t helpless, though. It can kick hard, bite hard, and if the dingo gets its head over the wombat’s back to grab for its neck, the wombat will push upward and crush the dingo’s head against the roof of the tunnel. The wombat takes no prisoners and presents its butt to danger. Also, its poop is square, as you may remember if you listened to the animal poop episode.

The wombat has a very slow metabolism and takes a week or even two weeks to fully digest a meal. It can run fast when it needs to, although it can’t keep up a fast pace for long. Wombats have even been known to knock people down by charging them, which I personally find hilarious. It can also bite ferociously if it feels threatened, and while it mostly uses its long claws for digging, they also make fearsome weapons. So it’s best to leave the wombat alone.

The wombat’s fur can be gray, tan, brown, black, or any variation on those colors, but there are rare reports of wombats with golden fur. In a 1965 letter to The Times, an anonymous writer reported spotting a golden wombat but couldn’t get anyone to believe him. “Of course you were mistaken, my family said. They said it with an irritating sureness… The golden wombat became the subject of family jokes.” And then two years later, the letter-writer saw the golden wombat again. I thought that would be a fine cryptozoological mystery to share, but when I did a search for golden wombat sightings, actual golden wombats in zoos turned up. Golden wombats are a real thing, just extremely rare. The sunshine golden fur is due to a mutation in coat color.

The Cleland Wildlife Park in Adelaide has a pair of golden hairy-nosed wombats that were discovered in 2011 and sent to the park in 2013. Golden wombats don’t survive long in the wild since their coloring makes them stand out to predators. Wombats in general are having trouble in the wild anyway due to habitat loss, introduced predators like domestic dogs, introduced rabbits and other animals that compete with it for food, the mange mite, also introduced to Australia and spread by domestic dogs, and drought.

Last year, during the awful summer bushfires in Australia, there were reports of wombats saving other animals by herding them into their deep burrows when fires approached. It’s a great story, but like many other stories that seem too good to be true, it’s not completely accurate. The wombats didn’t herd other animals into their burrows like little furry firefighters, but lots of animals did take shelter in wombat burrows to escape the fires. A wombat’s burrow isn’t just a little tunnel with a bedroom at the end. It’s way more elaborate than that, with lots of entrances and adjoining tunnels. One wombat’s burrow complex had 28 entrances and almost 295 feet of tunnels, or 90 meters. A wombat usually only sleeps in one particular burrow for a day or two before moving to a different one, and other animals routinely use the other burrows for themselves. As long as the other animal isn’t a threat, the wombat doesn’t seem to mind. So it’s not surprising that lots of animals hide in wombat burrows to escape fire.

In October of 2020 a team of scientists published a paper about ultraviolet fluorescence in the platypus, which glows greenish in ultraviolet light. The discovery was made by accident but prompted scientists throughout the world, and especially Australia, to borrow black lights from other departments to shine on their mammal collections. It turns out that a lot of nocturnal or crepuscular animals have fur that glows various colors under ultraviolet light. This includes the wombat.

There’s more ultraviolet light at dawn and dusk than during full daylight or at night, so some researchers think the glow may be a way for the animals to blend in with the increased ultraviolet light at those times. If this is the case, it’s a new type of camouflage, or rather a very old type since it’s found in animals like the platypus that have been around for a really, really long time.

Ultraviolet light is the wavelength of light beyond purple, which humans can’t see. Most humans, anyway. In April 2019 I released a Patreon episode about animals and ultraviolet light, and I’ve decided to unlock that episode for anyone to listen to. I’ll put a link in the show notes so you can click through and listen. Be aware that I did make a mistake in that episode, where I mentioned that a black light allows humans to see into the ultraviolet spectrum, but actually what people see when they shine a black light around is fluorescence and ordinary violet light.

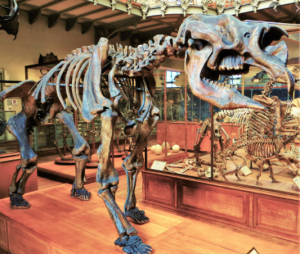

A relative of the wombat, Diprotodon, is the largest marsupial ever known. It went extinct around 45,000 years ago, not long after the first humans populated Australia, and is also an ancestor of the koala. It and some other of the Australian megafauna may have influenced Aboriginal myths of dreamtime monsters. It stood around 6 ½ feet tall at the shoulder, or two meters, and like the wombat it had a rear-facing pouch and ate plants. Recent analysis of the front teeth, which were large and flat and grew continuously throughout the animal’s life, indicated it might have been migratory. Researchers also think it lived in social groups something like elephants do today. Its feet were flat and toed inward like modern wombat feet, and although it had claws it probably only used them to dig plants up.

A partial fossil found in 1973 in South Australia was finally described in mid-2020 as a wombat relation, although it may not be a direct ancestor to modern wombats. It lived about 25 million years ago and was the size of a bear, and had powerful front legs with claws used for digging up roots. It’s named Mukupirna nambensis and is different enough from other wombat relations that it’s been assigned to a new family of its own.

There have been reports for centuries of giant wombats or wombat-like animals in Australia and even from nearby Papua New Guinea. Some cryptozoologists think the sightings are of a smaller relative of the wombat, Hulitherium tomasetti. Hulitherium lived in the rainforests of New Guinea, and probably went extinct about the same time as Diprotodon, possibly due to hunting from newly arrived humans. It was about three feet high, or one meter, and may have eaten bamboo as a primary part of its diet. Like the panda, it seems to have a number of adaptations to feeding on a bamboo diet, including very mobile front legs, more like an ape’s than a wombat’s. It may have been able to stand on its hind legs like a bear too.

An October 26, 1932 story in The Straits Times, a Singapore newspaper, is interesting in light of the hulitherium’s size and possible appearance. I’ll quote the story, which appears in the 2016 Fortean Zoology Yearbook:

“One of our strangest visits was reserved for this morning, when Mr. Paul Pedrini, wild animal hunter and trainer, arrived leading a curious beast, brown, furry, about two feet high and four feet long and looking like no animal one could call to mind. It was very fat and adorning its neck was a large pink bow. This latter fact was the chief cause of the uneasiness shown by the oldest sub-editor. Mr. Pedrini explained that he found his little pet in Australia eighteen months ago.

“He calls it the ‘What Is It?’ because nobody can give it a name. Described as being something like a wombat, it is certainly not a wombat neither does it belong to any other known family. The ‘What Is It?’ is very tame and friendly and has kind eyes. Its chief diet is bananas and toast. We said good bye to Mr. Pedrini, patted the strange animal and returned, slightly shaken, to the normal round.”

The story isn’t sensational enough to feel like a hoax, but it doesn’t really give enough of a description of the animal to be sure it wasn’t just a larger than usual wombat. After all, the wombat does have kind eyes.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!