Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 7:59 — 9.1MB)

We have merch available again!

Thanks to Will for suggesting this week’s topic, the burrunjor!

Muttaburrasaurus had a big nose [picture by Matt Martyniuk (Dinoguy2) – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3909643]:

The “rock art” that Rex Gilroy “found”:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

Recently, Will suggested we learn about an Australian cryptid called the burrunjor. As it happens, this is a short chapter in my book Beyond Bigfoot & Nessie: Lesser-Known Mystery Animals from Around the World, which is available to buy if you haven’t already. I’ve updated it a little from the chapter, so even if you have the book I think you’ll find this a fun episode.

Dinosaurs once lived in what is now Australia, just as they lived throughout the rest of the world. Similar to the southwestern United States reports of little living dinosaurs that we talked about in episode 252, some people in northern Australia report seeing living dinosaurs running around on their hind legs—but these dinosaurs aren’t so little.

The burrunjor, as it’s called, is often described as looking like a Tyrannosaurus rex. Mostly, though, people don’t actually see it. Instead, they hear roaring or bellowing and later see the tracks of a large, three-toed animal that was walking on its hind legs.

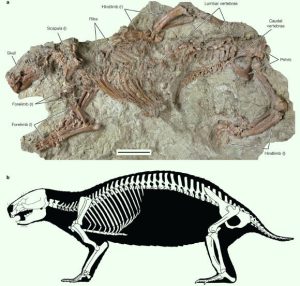

One Australian dinosaur that people mention when trying to solve the mystery of the burrunjor is Muttaburrasaurus. It was an ornithopod that grew up to 26 feet long, or 8 meters. It walked on its hind legs and had a big bump on the top of its muzzle that made its head shape unusual. No one’s sure what the bump was for, but some scientists speculate it might have been a resonant chamber so the animal could produce loud calls to attract a mate. Other scientists think it might have just been for display. Or, of course, it might have been both—or something else entirely. None of the Australian dinosaur sightings mention a big bump on the dinosaur’s nose. Muttaburrasaurus also had four toes on its hind feet, not three, and it disappeared from the fossil record about 103 million years ago. It also probably ate plants, not meat.

Another suggestion is that the burrunjor is a megaraptorid that survived from the late Cretaceous. These dinosaurs looked like theropods but with longer, more robust arms. Most scientists these days group them with the theropods. Most of the known specimens are from what is now South America, but two species are known from Australia, Australovenator and Rapator.

Australovenator is estimated as growing up to 20 feet long, or 6 meters, and probably stood about the same height as a tall human. It was a fast runner and relatively lightly built. It disappeared from the fossil record around 95 million years ago, not that we have very many bones in the first place. We only know Rapator from a single bone dated to 96 million years ago. It was probably related to Australovenator, although some paleontologists think Australovenator and Rapator are the same dinosaur. Either way, it’s doubtful that any of these animals survived the extinction event that killed off all the other non-avian dinosaurs.

“Burrunjor” is supposed to be a word used by ancient Aboriginal people to describe a monstrous lizard that eats kangaroos. But in actuality, Burrunjor is the name of a trickster demigod in the local Arnhem Aboriginal tradition and has nothing to do with reptiles or monsters. The Aboriginal rock art supposedly depicting a dinosaur-like creature doesn’t resemble other rock art in the region and isn’t recognized by researchers or Aboriginal people as being authentic.

All accounts of the burrunjor trace back to a single source, an Australian paranormal writer named Rex Gilroy. Gilroy was the one who “discovered” the rock art of a supposed dinosaur and none of the sightings he reports appear in local newspapers. The first mention of the word burrunjor referring to a monster appears in 1995, when Gilroy’s book Mysterious Australia was first published. According to Gilroy, the most recent burrunjor sighting is from 1985, when a family driving to Roper River reported seeing a feather-covered dinosaur that was 20 feet long, or 6 meters. But again, that report doesn’t appear in the newspapers, just in Gilroy’s books.

Gilroy’s burrunjor is probably a hoax, but there is a big lizard in Australia that sometimes stands on its hind legs. Monitor lizards live throughout Australia and are often called goannas. The largest Australian species can grow over 8 feet long, or 2.5 meters. All monitor lizards, including the Komodo dragon that lives in Indonesia, can stand on their hind legs. The lizard does this to get a better look at the surrounding area. It uses its tail as a prop to keep it stable and can’t actually walk on its hind legs, but an 8-foot lizard standing on its hind legs might look like a dinosaur from a distance.

An even bigger monitor lizard, called Megalania, lived in Australia until at least 50,000 years ago and maybe much more recently. It’s possible that Aboriginal Australians lived alongside it, although there’s no evidence for this either way. (Unless you count the evidence that that would be really really cool.)

Megalania is considered the largest terrestrial lizard known. Dinosaurs weren’t lizards and crocodilians aren’t either, but monitor lizards are. We don’t have any complete fossils of Megalania but its total length, including its tail, is estimated to be as much as 23 feet long, or 7 meters. This is more than twice the length of the Komodo dragon, the largest lizard alive today and a close relation. Like the Komodo dragon, Megalania was probably venomous.

As for Rex Gilroy, he recently passed away at the age of 79 and his books about the burrunjor are out of print. Rest in peace, burrunjor man.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!