Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 10:21 — 11.4MB)

Thanks to Lydia and “warblrwatchr” for this week’s suggestions!

Further reading:

Sweet tooth: Ethiopian wolves seen feeding on nectar

The African wild dog is not actually a dog and eats lots of things:

The aardwolf is not a dog at all and eats insects:

The Ethiopian wolf is not a dog (or a wolf or a fox) and eats rodents and nectar [photo by Adrien Lesaffre and taken from this page]:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to talk about three dog-like animals from Africa, suggested by Lydia and “warblrwatchr,” even though none of the three animals are dogs.

We’ll start with one of Lydia’s suggestions, the African wild dog, also called the painted dog or painted wolf. Despite those names, it’s not very closely related to dogs and wolves. It’s the only species in its own genus, although it is a member of the family Canidae. Colonizers from Europe thought the animal was just a feral dog, not anything special that should be protected, and they also brought domestic dogs with them to Africa. Domestic dogs mean diseases that other canids can catch. Between introduced diseases, farmers killing the animals to keep them away from livestock, and habitat loss, the African wild dog is endangered. Luckily, these days conservation groups have been working to protect the animal, and its numbers are increasing slowly in Kenya’s national parks in particular.

The African wild dog is a tall, strong canid with great big ears and no dewclaws. It has a yellowish coat with black blotches and some white spots, including a white tail tip, although some subspecies have darker coats. Unlike most canids, its fur is bristly and doesn’t have a soft undercoat, and as the dog ages, it loses its fur until old dogs are nearly bald. It’s very social, as canids almost always are, and its varied coat pattern helps individuals recognize friends and pack-mates at a distance.

The African wild dog prefers savannas and other open areas. It hunts in packs and mostly preys on antelopes, although it will also kill zebras and other large animals, and individual dogs will sometimes catch small animals like hares and rodents.

The African wild dog pack isn’t especially hierarchical. The males of the pack are mainly led by the dominant male, while the females are mainly led by the oldest female, who is usually the most dominant. The dominant pair is usually the only pair that has babies. A mother dog has up to 16 pups at a time but only one litter a year.

In a lot of animals, as the babies grow up, the males are usually the ones who are driven out of the pack or leave on their own to find a new pack. In the African wild dog, females are the ones who leave as they grow up. Sometimes the females join a different pack and sometimes they start their own. Either way, it stops a pack from becoming inbred.

The African wild dog is extremely vocal, making lots of different sounds to communicate with its pack-mates. It sounds a lot more like a bird than a dog. This is what African wild dogs sound like:

[doggo sounds]

Next, Lydia and warblrwatchr wanted to learn about the aardwolf, which lives in eastern and southern Africa. Unlike the African wild dog, which is mostly active during the day, the aardwolf is nocturnal. It spends most of the day in a burrow, sometimes one it digs itself, but more often one that another animal dug and abandoned at some point.

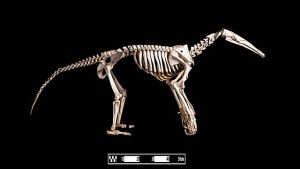

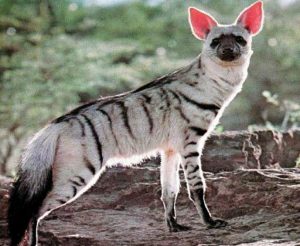

The aardwolf has black stripes on a yellowish or reddish coat, a mane of long hair down its neck and back, large ears, and a bushy tail. It’s about the size of a big dog, about 20 inches tall at the shoulders, or 50 cm, but it looks like a small, slender hyena. That’s because it is actually a type of hyena, although it’s not closely related to other hyenas. Hyenas look dog-like but they aren’t canids at all. In fact, they’re more closely related to cats than to dogs, although that’s a very distant relationship.

The aardwolf has evolved to eat insects, mainly termites. It has a broad, sticky tongue, and while it does have teeth, unlike the anteaters we talked about a few weeks ago, they’re not very strong and are mostly used to fight other aardwolves. It’s mostly solitary except during mating season, when a pair will stay together until the female’s cubs are a few months old. The male will watch the cubs while the female goes out to find food.

The aardwolf mainly defends its territory by marking it with secretions from its anal glands, although males will fight during mating season and a mated pair will chase other aardwolves away when they have babies.

Not only does the aardwolf mainly eat termites, it mainly eats termites in one particular genus. It doesn’t dig into the termite mound but smells and hears the termites that are outside of the nest, which it licks up. Then it moves on to another termite mound and licks up all the termites it finds there. This makes it easier for the aardwolf to find food without expending a lot of energy, and it also doesn’t risk destroying the termite colonies in its territory. It can easily eat a quarter million termites every single night. It licks up a lot of sand along with the termites, naturally, but the sand actually helps grind up the insects in its stomach.

The aardwolf will also eat other insects when it can’t find enough of its preferred termites. Sometimes it will eat bird eggs, beetle larvae, and other small food. It doesn’t typically eat meat at all, even dead animals it comes across. It just eats any insects and larvae it finds on the carcass.

Finally, let’s finish with the Ethiopian wolf. It’s also called the red jackal or the Simien fox. It looks a lot like a long-legged fox, with a reddish coat with white markings, big pointed ears, and a long, sharp muzzle. Its long fluffy tail has a black tip. But it’s not a type of fox at all. It’s also not a jackal. Even though it lives in Africa, a genetic study has revealed that it’s actually more closely related to the gray wolf and coyote of North America than it is to any of the canids that live in Africa. Scientists think that the ancestor of the gray wolf migrated into northern Africa from Eurasia and its descendant is the Ethiopian wolf.

The Ethiopian wolf lives only in the mountains of Ethiopia and is critically endangered due to habitat loss, diseases spread by domestic dogs, and poaching. Less than 500 individuals are left in the wild. It lives in large family groups, with only the dominant female breeding. The rest of the pack helps care for the pups when they’re born. But the Ethiopian wolf doesn’t usually hunt in packs. Instead, it’s specialized to hunt rodents, and almost never eats anything except rodents.

Or that’s what we thought, until an article was published just a few days ago as this episode goes live in November 2024. But to learn about an unusual addition to the Ethiopian wolf’s diet, first we have to learn about a flower.

The flower is called the poker plant, torch lily, or red hot poker, because its flowers are orange and yellow and grow in a spike at the end of an upright stalk. The orange spike looks like a fireplace poker that’s been left in the fire long enough that the metal has begun to glow. Its genus is Kniphofia, and all species are native to Africa although people in other parts of the world grow them in gardens. The flowers produce lots of nectar and attract lots of bees and sunbirds.

But it’s not sunbirds or bees that the wolves have been observed eating. It’s the nectar itself, which the wolves lick off the flowers. This isn’t all that unusual, since lots of animals like the sweet taste of nectar. One of the scientists had seen the children of local shepherds lick the flowers for nectar, and she tried it too and said the nectar was delicious. She then saw the wolves lick the flowers, and after some study, it turns out that it’s very common behavior among the wolves. Older wolves teach pups how to do it, and the team observed some wolves visiting up to 30 different plants to lick nectar from the flowers.

The surprising thing, though, is what happens when a wolf licks the nectar. Pollen from the flowers gets all over the wolf’s muzzle, including on its whiskers. If you have a dog, you know that dogs have lots of little thin whiskers around their muzzle, and it’s the same for the Ethiopian wolf. As the scientists observed wolves visiting flower after flower, they realized that it’s probable that the wolves are helping pollinate the red hot poker flowers.

If this is the case, it’s the very first known large predator to act as a pollinator. Not only that, this is the first large predator found feeding regularly on nectar. Just like a giant meat-eating bee.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!