Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 11:29 — 11.7MB)

It’s April Fool’s Day, but while these two mystery animals may mostly be associated with hoaxes and tall tales, there’s a really interesting nugget of truth in both.

Unlocked Patreon episode about mammals with nose horns

Further reading: Dr Karl P N Shuker’s blog post about winged cats and his blog post about horned hares

Traditional drawings of horned hares:

You can take classes in taxidermy that specialize in making jackalopes!

A genuine horned hare (with an extreme case of SPV):

A winged cat:

Mitzi/Thomas the winged cat:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This episode releases on April Fool’s Day, April 1. I’m not a fan of April fool jokes, so we’re going to discuss two interesting strange animals that turned out to be hoaxes—but hoaxes with a nugget of truth that’s actually more interesting than the hoax.

The first hoax is akin to the jackalope and it’s pretty obvious to us nowadays. The horned hare was a tradition in European folklore and drawings of it look like a jackalope. There are even stuffed horned hares, just as there are stuffed jackalopes.

Some of you may be wondering what the heck a jackalope is, so I’ll explain that first.

The jackalope legend may have started as a tall tale, but was probably just a taxidermy joke. When someone prepares a dead animal for taxidermy, it’s not a simple process. The taxidermist has to remove the skin from the body, clean it and add preservatives, make a careful armature or mannequin of the body out of wood or other materials, and put the skin on the armature and sew it up. The taxidermist then adds details like glass eyes and artificial tongues. It can take months of painstaking work to finish a specimen, and it requires a lot of artistry and training. Taxidermists who are learning the trade will often mount small, common animals like rabbits and rats as practice. And sometimes they’ll get creative with the process, just to make it more interesting. For instance, a taxidermist may add pronghorn antelope horns to a jackrabbit. Voila, there’s a jackalope!

You can see stuffed jackalopes today in a lot of places, since they’re fun conversation pieces. Some restaurants will have one stuck up on a wall somewhere, for instance. Horned hares are similar, but instead of a jackrabbit with pronghorn horns or white-tailed deer antlers, which are animals from North America, the European horned hare is usually a European hare with horns [I should have said antlers] from a roe deer.

The horned hare was such a common taxidermied animal that people actually believed it was real. Eventually, around the 19th century, as knowledge of the natural world grew more sophisticated, scientists realized rabbits and hares don’t have horns and those stuffed specimens were just hoaxes. The tip-off was probably when taxidermists started getting really fancy and adding bird wings and saber teeth to their mounted hares.

But…

The horned hare goes way back in history. It appeared in medieval bestiaries, sometimes called the unicorn hare. The unicorn hare was supposed to have a single black horn on its head. The hare would act normal, but when someone approached, it would spring at them and stab them with its horn. Then it would eat them. The legend of the horned hare is so widespread and long-lived, in fact, and was believed for so long, that it’s easy to think maybe it was based on something real. I mean, we just talked about rodents with nose horns a few weeks ago, so nothing’s impossible.

Wait, I think that’s a Patreon episode. If it is, I’ll unlock it. I’ll put a link in the show notes.

There is a strange truth behind all the jackalopes and horned hares. A disease called the Shope papilloma virus, or SPV, affects hares and rabbits. There are a lot of papilloma viruses in various animals, even humans, but in most animals, including humans, it only results in tumors in the body. In rabbits and hares, it causes keratinized tumors to grow from the skin, often on the head. Usually these are small and don’t show through the fur, but sometimes an animal has an extreme case of SPV and it genuinely looks like it has horns. The horns are hard and usually dark in color. As if that wasn’t bad enough, rabbits and hares in Europe can also get a disease called Leporipoxvirus that again causes facial horns to grow from the skin.

If you’re feeling totally creeped out right now, don’t worry, humans can’t catch these diseases from rabbits and hares.

Remember how I mentioned taxidermied hares with wings? What about cats with wings—but not taxidermied, real live domestic cats with fur-covered wings. That totally can’t be real, right? It’s not real?

It’s real…but only if you are really generous with what you mean by wings.

Winged cats are a real phenomenon, but the wings in question are furry, not feathered, and winged cats can’t fly. That doesn’t stop people from claiming they’ve seen these winged cats flying around causing mischief. For instance, in Ontario, Canada in 1966 a so-called vampire cat was supposedly flying around attacking other animals. It was a black tomcat with furry wings 7 inches long, or 18 cm. Eventually someone shot the cat, which was examined by veterinarians and found to be rabid. Its wings were nothing but thickly matted fur, so the stories of it flying around weren’t true, although sadly, it was definitely attacking other animals due to having rabies.

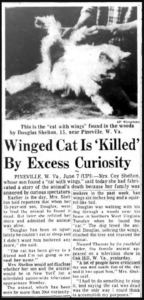

In 1959, a case went to court in West Virginia over a winged cat. A 15 year old boy named Douglas Shelton said he’d rescued the cat from a tree and adopted her. But a woman named Mrs. Hicks said that the cat was hers, named Mitzi, but that Mitzi had run away and she wanted her back. This makes sense. I mean, I would want my cat back too. At first the judge awarded the cat to Mrs. Hicks, but when Douglas brought her into the courtroom, she had no wings. Douglas said she’d shed them during the summer but he’d kept the wings, which he showed to the judge. At that point, Mrs. Hicks suddenly decided she didn’t want the cat after all. Frankly, I’m sure Mitzi was better off with Douglas, who didn’t care if she had wings or not, although he did change Mitzi’s name to Thomas.

Stories like these didn’t just happen back in the olden days. There are lots of winged cat reports today, including photos and videos. What’s going on? Why do some cats develop these furry appendages that people call wings?

Sometimes the cats in question just have long fur that has become unusually matted and appears to form winglike flaps along the sides. But in many cases, the wings are due to a rare skin condition called feline cutaneous asthenia, or FCA.

Cats with FCA have unusually elastic skin. All skin stretches at least a little bit but almost immediately snaps back into place. You can try this yourself by gently tugging up the skin on the back of your hand and releasing it. But in cats with FCA, the skin doesn’t snap back properly, especially the skin along the shoulders and back. Since in the ordinary course of living its life, a cat’s skin stretches quite a bit along the back, eventually an FCA cat ends up with long flaps of furry skin that stretched and didn’t snap back repeatedly. The wings aren’t really wings, of course, and can’t allow the cat to fly.

Cats with FCA do usually need special care, especially if the case is severe. The skin is elastic, but it’s also prone to damage because it’s actually very delicate. The so-called wings sometimes tear off naturally, leaving wounds that bleed very little but still need to be treated by a veterinarian. They then reform. The wings tend to be on the sides near the hind legs but are sometimes closer to the shoulders.

Mitzi, AKA Thomas, was definitely a cat with FCA. Her wings were six inches long, or 15 cm, and her tail was described as squirrel-like. She was a white cat described as a Persian, although she may have just had long hair like a Persian cat. A reporter who examined Thomas described her wings as fluffy at the ends but with a gristly feel at the base, as though they contained tendons or other structure. This was probably the extended skin due to FCA.

It sounds like Douglas was a really nice kid who rescued the cat from the tree and took her home, and when his friends made fun of the unusual-looking cat, he was really upset. Once word of the winged cat got around, people started showing up at the family’s house to look at it. At first Douglas charged 10cents to see the cat, and he was even invited to New York where he and Thomas appeared on the Today Show.

But after that, things started to go kind of nuts. Thousands of people kept trying to see the cat, so many that Douglas’s mom spread the story that the cat had died, just so people would leave the family alone. She also took the cat to a friend’s house for a while until the fuss died down, swearing the friend to secrecy that the cat was still alive. Then Mrs. Hicks sued.

I tried to find out what happened to Douglas Shelton and Thomas after all the excitement died down. Douglas and his family were awarded custody of Thomas by the judge, with Mrs. Hicks rewarded a single dollar in damages, but whatever happened after that has vanished into the pre-internet vacuum. I’m sure Thomas lived a good life with the Sheltons, and Douglas is probably still alive today. He would be about the right age to be a granddad by now, so I bet he tells his grandkids stories about the time he had a cat with wings. I bet they don’t even believe him.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!