Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 16:26 — 17.7MB)

Part two of our humans episode is about a couple of our more distant cousins, the Flores little people (Homo floresiensis) and Homo naledi, with side trips to think about Rumpelstiltskin, trolls, and the Ebu gogo.

Homo floresiensis skull compared to a human skull. We are bigheaded monsters in comparison. Also, we got chins.

Homo naledi’s skull. I stole that picture from Wits University homepage because I really liked the quote and it turns out it’s too small really to read. Oh well.

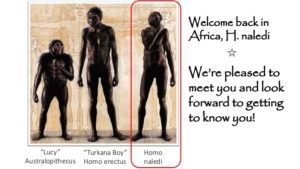

Some of our cousins. Homo erectus in the middle is our direct ancestor. So is Lucy, an Australopithecus, although she lived much longer ago.

Show transcript

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week is part two of our humans episode. Last week we learned how modern humans evolved and about two of our close cousins, Neandertals and Denisovans. This week, we’re going to walk on the weirder side of the hominin world.

Before we get started, this episode should go live on July 31, 2017, one week before I fly to Helsinki, Finland for WorldCon 75! Don’t worry, I’ve got episodes scheduled to run normally until I get home. If you’re going to be in Finland between August 8 and August 17, let me know so we can meet up. On Thursday, August 10 and 4pm I’ll be on a panel in room 207 about how to start a podcast, so check it out if you’re attending the convention. I’ll also be in Oslo during the day on August 7 and have two birding trips planned with lunch in between, and I’d love you to join me if you’re in Oslo that day too. Then, two weeks after I return from Finland, I’ll be attending DragonCon over Labor Day weekend. blah blah blah this is old news

Now, let’s learn about some of our stranger distant cousins!

In 2003, a team of archaeologists, some from Australia and some from Indonesia, were in Indonesia to look for evidence of prehistoric human settlement. They were hoping to learn more about when humans first migrated from Asia to Australia. One of the places they searched was Liang Bua cave on the island of Flores. They found hominin remains all right, but they were odd.

The first skeleton they discovered was remarkably small, only a bit more than three and a half feet tall [106 cm] although it wasn’t a child’s skeleton. That skeleton was mostly complete, including the skull, and appears to be that of a woman around 30 years old. She’s been nicknamed the Little Lady of Flores, or just Flo to her friends. Officially, she’s LB1, the type specimen for a new species of hominin, Homo floresiensis.

But until very recently, that statement was super controversial. In fact, there’s hardly anything about the Flores remains that aren’t controversial.

At first researchers thought the remains were not very old, maybe only twelve or thirteen thousand years old, or 18,000 at the most. Stone tools were found in the same sediment layer where Flo was discovered, as were animal bones. The tools were small, clearly intended for hands about the size of Flo’s, which argued right off the bat that she was part of a small-statured species and wasn’t an aberrant individual.

The following year, 2004, the team returned to the cave and found more skeletal remains, none very complete, but they were all about Flo’s size. Researchers theorized that the people had evolved from a population of Homo erectus that had arrived on the island more than three quarters of a million years before, and that they had become smaller as a type of island dwarfism. A volcanic eruption 12,000 before had likely killed them all off, along with the pygmy elephants they hunted.

But as more research was conducted, the date of the skeletons kept getting pushed back: from 18,000 years old to 95,000 years old to 150,000 years old to 190,000 years old. Dating remains in the cave is difficult, because it’s been subject to flooding and partial flooding over the centuries. Currently, the skeletal remains are thought to date to 60,000 years ago and the stone tools to around 50,000 years ago.

When news of the finds was released, the press response was enthusiastic, to say the least. The skeletons were dubbed Hobbits for their small size, which made the Tolkien estate’s head explode, and practically every few weeks it seems there was another article about whether there were small people still living quietly on the island of Flores, yet to be discovered.

And, of course, there were lots of indignant scientists who were apparently personally angry that the skeletons were considered a new species of hominin instead of regular old Homo sapiens. Part of the issue was that only one skull has ever been found. It’s definitely small, and the other skeletal remains are all correspondingly small, and the stone tools are all correspondingly small, and the skull shows a number of important differences from that of a normal human. But that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s not a subspecies of Homo sapiens, and of course that needs to be investigated. But some of the arguments got surprisingly ugly. There were even accusations that the entire find was faked. One person even suggested that the skull’s teeth showed evidence of modern dental work.

Amid all this, two unfortunate things happened. First, in December 2004 an Indonesian paleoanthropologist named Teuku Jacob removed almost all the bones from Jakarta’s National Research Centre of Archaeology for his own personal study for three months. When he returned them, two leg bones were missing, two jaw bones were badly damaged, and a pelvis was smashed. Then, not long after, Indonesia closed access to Liang Bua cave without explanation, although the archeological community suspected it was due to Jacob’s influence, and didn’t reopen it until 2007 after Jacob died.

It’s important to note that Jacob was a proponent of the theory that the remains found in Liang Bua cave were microcephalic individuals of the prehistoric local population, not a new hominin species at all. He also had a history of keeping Indonesian fossils from being studied unless he specifically approved of the research.

At any rate, since then, repeated studies of the LB1 skull have suggested that Homo floresiensis is a separate species of hominin and not a Homo sapiens with evidence of pathology, whether microcephaly or another disease, or a population with a genetic abnormality. There’s still plenty of research needed, of course, and hopefully some more skulls will be found. But it seems clear that Homo floresiensis isn’t just a weird subspecies of Homo sapiens.

One of the more common theories in the last few years was that Homo floresiensis was descended from Homo erectus, although Homo erectus was a lot bigger and more human-like than the Flores little people. But results of a study released just a few months ago show that Homo floresiensis shared a common ancestor with Homo habilis around 1.75 million years ago. Homo floresiensis may have evolved before migrating out of Africa, or their ancestor migrated and evolved into Homo floresiensis. Either way, they spread as far as Indonesia before dying out around 50,000 years ago.

Other hominin remains have since been found on the island. Part of a jaw and teeth were found at Mata Menge on the island of Flores, some 50 miles away from the cave. It’s around 700,000 years old and is a bit smaller than the same bones in the later skeletons. Researchers think it’s an older form of Homo floresiensis.

Possibly not coincidentally, modern humans arrived on the island about 50,000 years ago, maybe earlier, bringing with them the arts of fire, painting, making jewelry from animal bones, and killing all of our genetic cousins.

We don’t know if humans deliberately killed the Homo floresiensis people or if they just outcompeted them. It does seem pretty certain that the two hominin species coexisted on the island for at least a while. It’s even possible that knowledge of the strange small people of the island has persisted in folk tales told by the Nage people of Flores. Stories about the ebu gogo have been documented for centuries. They were supposed to be little hairy people around three feet tall [one meter], with broad faces and big mouths. They were fast runners with their own language and would eat anything, frequently swallowing it whole. In some stories they sometimes kidnapped human children to make the children teach them how to cook, although the children always outwitted the ebu gogo.

Supposedly, at some point, tired of their children being kidnapped and their food being stolen, villagers gave the ebu gogo palm fibers so they could make clothes. The ebu gogo took the fibers to their cave, and the villagers threw a torch in after them. The fiber went up in flames and killed all of the ebu gogo.

Until the discovery of Homo floresiensis, anthropologists assumed the stories were about macaque monkeys. But there’s a genuine possibility that the ebu gogo tales are memories of Homo floresiensis. It’s not just cryptozoologists and bigfoot enthusiasts making the connection between the ebu gogo and Homo floresiensis. Articles and editorials have appeared in journals such as Nature, Scientific American, and Anthropology Today. At least, they did back when archeologists thought Flo was only about 12,000 years old.

But we still don’t know for certain when Homo floresiensis went extinct. There may be remains that are much more recent than 50,000 years ago. Locals mostly say there are no ebu gogo left but that they were still around about a century ago. I don’t know how long historical elements can persist in an oral tradition without becoming distorted. As we discussed in episode 17, about Thunderbird, oral history is easily lost if the culture is disrupted by invasion, disease, war, or other major episodes. But some stories are tougher than others, and those that are less history and more entertainment—although they may contain warnings too—can be very, very old.

Researchers have traced some traditional folktales, like Rumpelstiltskin, back some 4,000 or even 6,000 years, although not without controversy. But while Rumpelstiltskin is usually described as a small person, no one’s suggesting that story is about real events. It’s the juxtaposition of the Flores discoveries of small skeletons and the oral tradition or small people living on the island that got researchers excited. And as it happens, there is an oral tradition many miles and many cultures away from Flores that might be something similar.

Old Norse stories about trolls date back thousands of years. The trolls vary in appearance and sometimes have a lot of overlap with other monsters, but generally are described as big and strong, not very smart, often placid unless provoked, and usually evil, or at least godless. Sometimes they capture humans who outwit them to escape. In one story, a man named Esbern Snare wanted to marry a woman, but her father would only agree to the marriage if Esbern would build a church. Esbern struck a deal with a troll, who said he would build the church—on one condition. If Esbern couldn’t guess the troll’s name by the time the church was built, the troll would demand as his payment Esbern’s heart and eyes.

Esbern agreed, but he failed to trick the troll into telling him his name. On the final day, in despair Esbern threw himself down on the bank of a river, where he overheard the troll’s wife singing to her baby:

“Hush, hush, baby mine,

Tomorrow comes Finn, father thine,

To bring you Esbern’s heart and eyes

To play with, so now hush your cries.”

Esbern rushed back to the church and greeted Finn the troll by name. In some version of the story, Finn is so furious that he leaves the church incomplete in some way, usually a missing pillar. For those of you who aren’t familiar with the Rumpelstiltskin story, that’s a variant. Oh, and Esbern Snare was a real person who lived in the twelfth century, although I’m pretty sure he didn’t actually strike any deals with trolls.

But I do wonder if some elements of troll folklore might be derived from memories of Neandertal people. I’m not the first to suggest this, although it is a pretty fringey theory. And in the end, we just don’t have any way to know. But it is interesting to think about.

As you may remember from part one of the humans episode, Homo sapiens evolved roughly 200,000 years ago. But around the same time, or a little earlier, another cousin in our family tree was living in southern Africa. Remains of Homo naledi were only discovered in 2013 by some cavers. Partial skeletons from at least 15 individuals were recovered in one field season, but due to narrow cave passages, the field work had to be done by people of small stature who weren’t claustrophobic, mostly women.

Homo naledi is a mixture of primitive and advanced features. Primitive in this case means more like our ape ancestors, and advanced means more like modern humans. Homo naledi had long legs and feet that looked just like ours, but also had a small brain and fingers that are much more curved than ours—not characteristics that would look out of place a few million years ago, but surprising to discover in our family tree at about the same time that modern humans were evolving.

On the other hand (with curved fingers), evolution doesn’t have an end goal. Homo sapiens is not the pinnacle of creation to which all other living beings aspire. We’re just another animal, just another great ape. If Homo naledi was successful in their environment with a small brain, that’s all that matters from an evolutionary standpoint.

There are lots of remains left in the cave, so many in fact that some researchers are convinced they didn’t get there by accident. It’s possible that the cave was used as a burial pit, maybe even over the course of centuries. Bodies may have been dropped in a deep shaft and were then moved by periodic flooding to the remote chamber where they were found, or they may have been carried to the cave depths and left there.

Homo naledi wasn’t a direct ancestor of Homo sapiens, but they were definitely a kind of human—no matter how small their brains may have been.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us and get twice-monthly bonus episodes for as little as one dollar a month.

Thanks for listening!