Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 21:36 — 21.9MB)

Ever heard of the Piltdown Man? What about Missourium or Archaeoraptor? They’re all frauds! Let’s learn about them and more this week.

Further reading:

The Chimeric Missourium and Hydrarchos

Missourium was literally an extra mastodon:

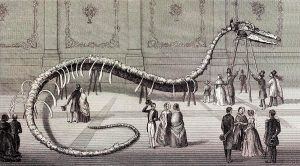

Hydrarchos (left) was a lot more, um, exciting than its fossil donors, six Basilosauruses (right):

![]()

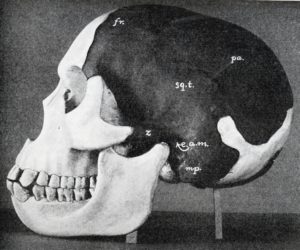

Piltdown man’s suspicious skull:

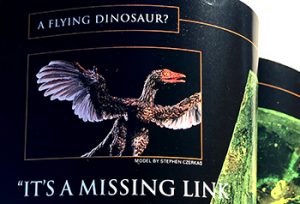

A lot of people were excited about Archaeoraptor:

Not a pterosaur:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

Last week we learned about some mistakes paleontologists made while working out what an extinct animal looked like using only a few fossilized bones. Mistakes are a normal part of the scientific method, no matter how silly they seem once we know more about the animal. But this week we’re going to look at some frauds and hoaxes in the paleontology world.

We really need to start with a man named Albert Koch. He was from Germany but moved to the United States in 1835, and was something of a cut-rate PT Barnum. He called himself Dr. Koch although he hadn’t earned a doctorate. A lot of the so-called curiosities he displayed were fakes.

Back in the mid-19th century, fossils had only recently been recognized as being from animals that lived millions of years before. People were still getting their heads around that concept, and around the idea that animal species could even go extinct. Then the fossils of huge animals started to be discovered—and not just discovered, but displayed in museums where the public could go look at them. Naturally they were big hits.

Sometimes these fossil exhibits weren’t free. For example, the mounted fossil skeleton of a mastodon was exhibited by the naturalist Charles Peale starting in 1802—one of the first fossil exhibits open to the public. Peale and his workers had mounted the skeleton to seem even larger than it really was by putting wooden discs between some of the bones. But the exhibit was primarily meant to educate, not just bring in money. It cost 50 cents to see the mastodon and lots of people wanted to. These days Peale’s mastodon is on display in Germany, without the wooden discs.

Albert Koch knew about Peale’s mastodon, and more to the point he knew how much money Peale had made off his mastodon. Koch wanted one for himself.

In 1840 he heard about a farmer in Missouri who had dug up some huge bones. Koch bought the bones and assembled them into a mastodon. But Koch wasn’t a paleontologist, he didn’t care about educating the public, and when he looked at those fossils, he just saw dollar signs. And he had ended up with bones from more than one mastodon, so, you know, he used them all. And he added wooden discs between the bones to make the animal bigger. A lot bigger. Between the wooden discs and the extra bones, Koch’s skeleton was twice the size of a real mastodon. Plus, he turned the tusks around so that they pointed upward, either because he didn’t know any better or because he thought that looked more exciting.

He called his mastodon Missourium and displayed it at his exhibit hall in St. Louis, Missouri later in 1840. It was a hit, and in 1841 he decided he’d make more money if he took Missourium on the road. He packed the massive skeleton up, sold his exhibit hall, and went on tour with just the mastodon.

Paleontologists spoke out against Koch’s Missourium as being unscientific, but that only gave him free publicity. People thronged to his exhibit for the next two years, until 1843 when he sold it to the British Museum. Needless to say, the experts at the British Museum promptly disassembled Missourium so they could study the fossils properly before remounting them into a mastodon that didn’t contain any extra ribs and vertebrae. Also, they put the tusks on the right way up.

But Koch wasn’t done riding roughshod over paleontology. To learn about what he did next, we have to learn about an animal called Basilosaurus.

Despite its name, Basilosaurus isn’t a dinosaur or even a reptile. It’s a mammal—specifically a whale, although it didn’t look like any whale alive today. It probably grew up to 70 feet long, or over 21 meters, with long jaws full of massive teeth—more like a crocodile or mosasaur than a whale. It had short flipper-like front legs that still had an elbow joint. Modern whales don’t have elbows. It also had little nubby hind legs, but the legs were far too small to support its weight on land. It probably mostly lived at or near the surface of the ocean since its vertebrae were large, hollow, and filled with fluid, which would have made Basilosaurus buoyant. It wouldn’t have been able to dive much at all as a result. It ate sharks and fish as well as smaller whale relatives.

Basilosaurus went extinct around 34 million years ago. Modern whales aren’t related to it very closely, although modern whales did share an ancestor with Basilosaurus. But Basilosaurus was a common animal and its fossils are relatively common as a result. They were so common, in fact, that they were sometimes used as house supports in parts of the American South.

In 1835 a British naturalist named Richard Harlan examined some fossils found in Alabama and decided it was a marine reptile, which he named Basilosaurus, which means king lizard. The mistake was corrected soon after when another paleontologist determined that the animal was a whale-like mammal, but it was too late to change the name due to taxonomic rules in place to minimize confusion. That’s why Basilosaurus is sometimes called Zeuglodon, since that was the name everyone wanted as a replacement for Basilosaurus.

In 1845, Albert Koch got hold of a lot of Basilosaurus fossils and decided this was his next big thing. And again, he didn’t care what Basilosaurus was or what it was called, he just wanted that moolah.

He constructed a mounted skeleton with the Basilosaurus fossils. But just as he did with his mastodon fossils, he didn’t arrange them as they appeared in life. He constructed a sea serpent that was 114 feet long, or almost 35 meters, and contained bones from six Basilosauruses, as well as some ammonite shells to bulk it out even more. He named it Hydrarchos and exhibited it first in New York City, then went on tour throughout the United States and Europe. It was even more popular than Missourium. Heck, I would have paid to see it.

Koch sold Hydrarchos to King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia, who exhibited it in the Royal Anatomical Museum in Berlin even though the paleontologists there really, really didn’t want it. Kock promptly bought more Basilosaurus bones and built a new fake, a mere 96 feet long this time, or 29 meters. He toured with it and sold it to another flim-flam artist in Chicago, who exhibited it until 1871, when the great Chicago fire destroyed it and most of the rest of Chicago.

Koch wasn’t the only person putting together real bones to make a fake animal back then, but at least he did it for the money. Other fakes were more insidious because we aren’t even sure why the hoaxer did it. That’s the case with the so-called Piltdown Man.

This is how the story goes. A man called Charles Dawson said that a worker at a gravel pit in Piltdown had given him a piece of skull in 1908. Dawson searched the pit and found more pieces, which he gave to a geologist at the British Museum, Arthur Woodward. Woodward and Dawson both returned to the gravel pit in 1912, where they found more pieces of the skull and part of a jawbone. Woodward reconstructed the skull from the pieces and reported that the ape in question must be a so-called missing link between humans and apes.

Just going to mention here that if anyone refers to a fossil as a missing link, you should be suspicious that maybe they don’t actually know what they’re talking about, or that the fossil is a fake.

Not everyone agreed with the reconstruction. In 1913, Woodward, Dawson, and a geologist and priest named Pierre Teilhard de Chardin returned to the gravel pit. Teilhard found an ape-like canine tooth that fit the jaw. But the tooth raised even more controversy, leading to the loss of friendships and colleagues splitting into camps for and against the Piltdown fossil. Teilhard de Chardin washed his hands of the whole thing and moved to France, and later helped discover Homo erectus, one of our direct ancestors.

Piltdown Man, of course, was a fake. Some people had already suspected it was a fake in 1912, and through the years afterwards people repeatedly examined the bones and kept pointing out that it was a fake. Now, of course, it’s easy for researchers to see that the jaw and teeth are from an orangutan while the skull is from a human. But for a long time, no one was sure who was behind the hoax. Was it Dawson, Woodward, Teilhard de Chardin, or all of them together? Or did someone else plant the fakes for those people to find?

In 2008, a team of experts decided to examine the fossil and the circumstances surrounding its so-called discovery. It took them eight years. They determined that the orangutan teeth were all from the same animal while the pieces of skull came from at least two different people and were possibly several hundred years old. The jaw and skull pieces had been treated with putty, paint, and stain to make them look fossilized, with some carving to make the bones match up better. The hoaxer had even crammed pebbles into the natural hollow places inside the bones, then puttied them over, presumably to make the bones weigh more and therefore feel more like fossils.

All these methods were the work of a single person, and experts have seen that person’s work before. Charles Dawson was an amateur geologist, historian, and archaeologist who “discovered” a lot of things, almost all of which have been proven to be hoaxes. But the Piltdown man hoax was the one that got him into the history books, even if only as a cheater.

So why did Dawson do it? It’s possible he wanted Britain to be home to a human ancestor more impressive than Homo heidelbergensis, which was discovered in Germany in 1907 and which was probably the common ancestor of humans and Neandertals. More likely, he just wanted to be part of the excitement of a big discovery, one which would bring him the respect of the professional scientists he envied. His other hoaxes had brought him a certain amount of fame and weren’t discovered during his lifetime, so he just kept making them.

You’d think the days of faked fossils were behind us now that paleontology is so much more sophisticated. But fake fossils are actually more of a problem now than ever, mostly because fossils can be worth so much money. Usually the fakes are obvious to experts, but sometimes they’re much more sophisticated and can fool paleontologists for at least a short time. And that brings us to Archaeoraptor.

In 1999, National Geographic announced the discovery of a feathered dinosaur fossil from China, which was a mixture of elements seen in both dinosaurs and birds. National Geographic called it a missing link between dinosaurs and birds.

Yep, another missing link.

Archaeoraptor looked like a small dinosaur but with feather impressions. This doesn’t sound weird to us now, but in 1999 it was shocking. Dinosaurs with feathers? Who ever heard of such a thing! Supposedly, the farmer who found the fossil had cemented the broken pieces together as best he could before selling it to a dealer. The fossil ended up in the United States where it was bought in early 1999 by The Dinosaur Museum in Utah for $80,000.

The National Geographic Society was interested in publishing an article about it in the magazine after the official description appeared in Nature. But Nature rejected the description. The paleontologists tried the journal Science next but again, Science rejected it. By then, other paleontologists who had examined the fossil reported that it wasn’t one fossilized animal but pieces from at least three different animals glued together to look like one. Albert Koche would be proud.

But National Geographic decided not to pull the article. It appeared in the November 1999 issue and the fossil itself was put on display at the National Geographic Society in Washington DC.

Meanwhile, a paleontologist named Xu Xing who’d seen the Archaeoraptor fossil thought it looked really familiar. He asked around in the area of China where Archaeoraptor was supposedly found, and eventually discovered the fossil of a small dinosaur called dromaeosaur. The tail of Archaeoraptor matched the tail of the Dromaeosaur fossil exactly—like exactly, right down to a yellow ochre stain in the same place. This doesn’t mean it was a fake or a copy, but that the two pieces had once been joined. Quite often fossils leave impressions on both sides of a piece of rock, which are called the slab and counterslab. Once Xing’s information got out, people started calling the fossil the Piltdown bird.

Remember last week when an extinct peccary tooth was misidentified as an ape tooth? People who didn’t believe evolution was real claimed that that one mistake proved they were right and all of science was wrong wrong wrong. Well, the same argument is going on today with people who still don’t believe evolution is real. For some reason they think that because Archaeoraptor was a hoax, evolution is somehow also a hoax—even though we now have plenty of perfectly genuine feathered dinosaur fossils that show how a branch of dinosaurs evolved into modern birds.

There are a lot of hoaxed fossils coming from China, which has some of the world’s most amazing fossil beds and some of the most amazingly well preserved fossils in the world. But because the people finding them are often desperately poor farmers, it’s common for fossils to be sold to dealers for resale. The dealers prepare the fossils and sometimes, to improve the resale value, they add details that aren’t really there to make the fossils seem more valuable. Even worse, the preparation by non-experts and those added details often destroy parts of the fossil that are then lost to science forever. And because the fossils are dug up by non-experts, paleontologists usually don’t know exactly where the fossils were found, which means they can’t properly estimate the fossil’s age and other important information.

Let’s finish with a very old hoax that was started for the best of reasons but took some unusual twists and turns. Way back in the late 17th century, the countryside near Rome in Italy kept getting flooded by rivers. Rumor had it that a dragon-like monster was responsible, that when it moved around too much in the river where it lived, the river overflowed its banks like water out of an overfull bathtub. In actuality the area is in a natural floodplain so of course it was going to flood periodically, but that didn’t make it any easier for the people who lived there.

A Dutch engineer, architect, and engraver named Cornelius Meyer had a solution, though, involving levees to make the River Tiber more navigable and less prone to flooding. He started the project around 1690 but had trouble with his local workers. They expected to come across the dragon at any moment, which made them reluctant to get too near the river.

So Meyer decided to show them that the local dragon was dead. In 1691 he “found” its remains and mounted them to put on display. The workers were satisfied and got to work building the levees that did exactly what Meyer promised, reducing flooding and saving many lives. No one knows what happened to Meyer’s dragon, but we have an engraving he made of it in 1696. You can see it in the show notes. It shows a partially skeletal monster with hind legs, bat-like wings, a long tail, and horns on its skeletal head.

Centuries later, in 1998 and again in 2006, two men saw the engraving reprinted in a book about dragons published in 1979 and decided it was a depiction of a recently killed pterosaur. Wait, what? Pterosaurs disappear from the fossil record at the same time as non-avian dinosaurs, about 66 million years ago. Why would anyone believe Meyer’s dragon was a pterosaur? It didn’t even look like one.

The two men were part of a group called the young-earth creationists, who believe the earth is only about 6,000 years old. In order to shoehorn the entire 4 ½ billion years of earth’s actual history into only 6,000 years, they claim that rocks only take a few years to form and that dinosaurs and other extinct animals either still survive today in remote areas or survived until modern times. I shouldn’t have to point out that their ideas make no sense when you understand geologic processes and other fields like cosmology, the study of the entire universe and how planets form. Young-earth creationists are always on the lookout for anything that fits their theories, like so-called living fossils and cryptids that resemble dinosaurs, like the mokele mbembe we talked about way back in episode two. I’m not sure why they think that finding a living dinosaur would prove that the earth is only 6,000 years old. All it would prove is that that a non-avian dinosaur survived the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event 66 million years ago.

Anyway, these two men decided that Meyer’s dragon was a pterosaur, which brought the engraving to the attention of modern scientists, who hadn’t known about it before. Obviously the dragon wasn’t actually a pterosaur. What was it?

The original remains were long gone, but the engraving was of extremely high quality. In 2013 researchers were actually able to determine what animal bones Meyer had used to make his dragon. The skull is from a dog, the jaw is from another dog, the ribs are from a large fish, the hind limbs are actually the front leg bones of a young bear, and so on. The wings, horns, and a few other parts are carvings.

Gradually, historians pieced together the real story behind Meyer’s dragon. We don’t know who actually made the fake dragon, but they did a great job. But it wasn’t a real dragon, and it definitely wasn’t a pterosaur.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!