Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 9:23 — 10.3MB)

This week we learn more about the blobfish thanks to Matilde’s suggestion, and we’ll also learn about a primitive rabbit.

Further reading:

In Defense of the Blobfish: Why the ‘World’s Ugliest Animal’ Isn’t as Ugly as You Think It Is

A rare rabbit plays an important ecological role by spreading seeds

The Amami Rabbit: A Living Fossil in the Wilds of Amami Ōshima [amazing photos in this article!]

The blobfish as we usually see it:

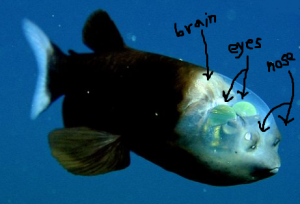

The blobfish as it looks when it’s in its deep-sea home:

The Amami rabbit is so so so round:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to learn a little more about the blobfish, which is Matilde’s suggestion, and we’ll also talk about an unusual primitive rabbit that’s still alive today.

We talked about the blobfish briefly in episode 231. The blobfish lives on the sea floor in deep water near Australia and New Zealand. It grows about a foot long at most, or 30 cm, and has weak muscles and a weak skeleton, but it doesn’t need to be any stronger since the intense pressure of the water presses in around the fish all the time. Its gelatinous flesh is slightly less dense than the water around it, which means it can float just above the sea floor without much effort, just drifting along, giving its tail and broad fins a little flap every so often. It eats whatever detritus floats down from far above, although it also really likes to eat small crustaceans that live on the sea floor.

But wait, you may be thinking, I’ve seen pictures of the blobfish and it looks like a pinkish blob with a cartoony frown and a droopy nose. Is that blobfish a different one from the one I just described?

No! The trouble is that the blobfish lives in really deep water, up to 4,000 feet below the surface, or 1200 meters. That means that there’s up to 4,000 feet of water above the fish, and if you’ve ever had to carry a bucket of water more than a few steps, you’ll know that water is really heavy. So the blobfish has 4,000 feet of water pressing on it from all directions. This is naturally called water pressure, and at the depths where the blobfish lives, it’s 120 times higher than water pressure in, for instance, your bathtub.

At that water pressure, you could not survive for even one second. You would be instantly crushed into a messy blob if you were suddenly transported into water that deep, because your body is adapted to live on the earth’s surface. But the opposite is true for the blobfish. If it was suddenly transported to the earth’s surface, or at least the water’s surface, without all that comfortable pressure keeping its body in place like a really big exoskeleton you can swim through, the blobfish would expand. And that’s exactly what happens when a fishing net catches a blobfish and pulls it to the surface. It just goes BLOB all over the place.

The blobfish was voted the world’s ugliest animal in 2013, which doesn’t seem fair since no one looks good when they’ve exploded into a blob.

When the blobfish is alive in its deep-sea home, it’s silvery or grayish with little spikes all over its body. It’s a member of the family Psychrolutidae, sometimes called toadfish, and it has little black eyes near the top of its head sort of like a toad. Its head is large and wide, while its body tapers to a thin little flat tail.

We know almost nothing so far about the blobfish, but we do know a bit about some of its close relatives like the blob sculpin. The blob sculpin lives in the North Pacific Ocean in even deeper water than the blobfish, up to 9200 feet deep, or 2800 meters. That’s about a mile and three-quarters deep, or almost 3 kilometers. Deep-sea animals are mostly solitary, but the blob sculpin gathers in large numbers to spawn. The females choose a nesting area and they all lay their eggs in the same place. Then the males release sperm into the water that fertilizes the eggs. Some nesting areas have been found to contain well over 100,000 eggs! Not only that, but the females guard the nesting area, and as they hover over their eggs, their slow-moving fins help keep the eggs clean of sand and sediment, which allows the eggs to absorb more oxygen. It’s the first documented case of a deep-sea fish taking care of its eggs.

Deep-sea animals often live for a long time, and it’s estimated that the blobfish might live to be as much as 130 years old.

That’s about all we know about the blobfish right now, so let’s finish with some information about a different cute round animal, although not a blobby one. It’s the Amami rabbit that only lives on two tiny islands off the southern coast of Japan.

The Amami rabbit used to live throughout Asia but as modern species of rabbit evolved, it eventually died out on the mainland. Now it only survives on these two small islands, and although it’s now a protected species, it’s still endangered. It’s especially vulnerable to habitat loss and introduced predators like dogs and cats. There are probably only about 5,000 individuals alive today, most of them on Amami Island with only a few hundred on Tokuno Island.

The Amami rabbit differs from other rabbits in a number of ways. Its eyes are smaller, its ears are smaller, and it’s shaped differently from other rabbits, with a chonky body and short legs. It also lives in forested areas instead of open grasslands. It’s nocturnal, with thick dark brown fur and long claws that it uses to dig burrows and climb steep hillsides.

A female Amami rabbit only has babies once a year, called kits or kittens, and usually only one or two kits are born at a time. In autumn the mother rabbit digs a special burrow that may be several feet deep, or up to a meter, somewhere away from her regular burrow. She brings leaves in to line the nesting chamber, where she gives birth to her kits. But she doesn’t stay with her babies all the time. In fact, she leaves them and only comes back to feed them about once a day or every other day. To keep them safe while she’s gone, she closes the entrance to the burrow so snakes and other predators can’t get in. When she returns, she digs the entrance open and spends a few minutes feeding her kits. Then she leaves again and closes the entrance behind her.

When the babies are a little over a month old, they start digging their way out of the nest on their own to explore. At that point the mother leads them to her home burrow where they stay for a few more months before they leave to find their own territories.

The Amami rabbit eats plants, especially grass and ferns, but it also eats acorns and fruit. A study published in January 2023 reported that the rabbit eats the fruit of a parasitic flowering plant called Balanophora, including swallowing the seeds whole. The seeds travel through the rabbit’s digestive system unharmed and the rabbit poops them out later, which allows them to sprout in an area far from the parent plant. Since Balanophora doesn’t produce chlorophyll and instead needs a host plant that can provide it with nutrients, having a rabbit help spread its seeds is important. This discovery was a surprise to the scientists studying the rabbit, because modern species of rabbit don’t usually eat seeds.

Who knows how many more surprises the Amami rabbit and the blobfish might hold? Hopefully scientists will continue to learn more about them so they can be better protected.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!