Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 12:19 — 12.7MB)

This week let’s learn about an amazing little fish and an awesome tortoise! All the pictures here were taken by ME at the Tennessee Aquarium in Chattanooga!

Further Reading:

Star tortoise makes meteoric comeback

The astonishing elephantnose fish:

Burmese star tortoises:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw. I’m fully vaccinated now so I’m able to go out and about cautiously, still wearing a mask of course, and this weekend I went to the Tennessee Aquarium in Chattanooga. I had a fantastic time and saw lots and lots of amazing fish and other animals! If you ever get a chance to visit, it’s definitely worth it.

When I got home, I kept thinking about one particular fish. I wanted to learn more about it. So I decided to make an episode about that fish and another animal I saw at the aquarium.

The fish that captivated me so much is called the elephantnose fish. I’d never seen anything like it. The one I saw was about the length of my hand, dark gray or black in color, and looked like a pretty ordinary fish except for the proboscis that gives it its name. The fish has a flexible projection from its nose that it was using to probe around in the gravel at the bottom of its river habitat.

I should mention that the Tennessee Aquarium has enormous displays, beautifully designed to mimic the animals’ natural habitat and give them plenty of room to move around. There’s one tidal animals display in the ocean side of the aquarium where the water sloshes through and around rocks to mimic the tide. It’s fascinating to watch the fish in that exhibit stay pretty much motionless despite the water’s movement, because that’s what they’re adapted for. So there’s plenty of opportunities to see an animal’s behavior.

Anyway, I took lots of pictures of the elephantnose fish and when I got home, I started researching it. It turns out that it’s way more interesting even than I thought!

It lives in rivers and other freshwater in central Africa and grows up to 9 inches long, or 23 cm. That’s according to the info display next to the exhibit. The display also said the fish was a species called Peter’s elephantnose fish, although it’s possible they have more than one species on display. There are a lot of elephantnose fish, more properly called mormyrids or freshwater elephantfish, and many of them have this interesting proboscis.

The proboscis isn’t actually a nose like an elephant’s trunk. It’s technically a modified chin and mouth, called the Schnauzenorgan. The elephantnose fish mostly eats small worms and insect larvae, and it especially loves mosquito larvae.

The elephantnose fish uses electroreception to navigate the muddy waters where it lives and find food. Its whole body, and especially its Schnauzenorgan, is covered with electrocyte cells that can detect tiny electrical pulses. If you remember way back in episode ten, about electric animals, many animals can sense the weak bioelectrical fields that other animals generate in their nerves and muscles. It’s especially common in fish since water conducts electricity much better than air does. But the elephantnose fish also generates a stronger electric field of its own, which it uses as a sort of sonar. It generates the field in special electric organs in its tail, and as it moves around in the water, the electric field comes in contact with other things—plants, rocks, other fish, and so on. It’s not strong enough to give an animal a shock, but it’s strong enough for the elephantnose fish to easily sense changes in its environment. The fish can tell what it’s near because its electrical field interacts differently with different things. A rock, for instance, doesn’t conduct electricity so the fish probably senses it as a blank spot in its electrical field, while a plant may conduct electricity even better than water and therefore changes the shape of the fish’s electrical field in a particular way. But it doesn’t generate its bioelectric field all the time. It can control when it discharges pulses of electricity the same way a dolphin can control when it sends out pulses of sound. If the fish feels threatened, maybe by another elephantnose fish nosing in on its territory, it will pulse much faster so it can keep tabs on what the other fish is doing—plus, of course, the other elephantnose fish can sense its pulses and can interpret how aggressive the first fish is. Female elephantnose fish generate a slightly different electrical field than males, which allows males and females to find each other to spawn.

You may be thinking about all this and wondering how the elephantnose fish can sense the tiny bioelectric charges of its tiny prey over its own electric field. Its electric field is much stronger than that of a teensy worm hiding in the mud, after all. It would be like trying to hear a bird chirping outside through a closed window while someone is playing music really loudly in the room you’re in. It turns out that the elephantnose fish is able to filter out its own electrical field so it can sense other things—but at the same time it’s still able to navigate using its electrical field.

The elephantnose fish needs a large brain to interpret all these complicated bioelectrical signals, and it has a brain to body size ratio equivalent to birds and possibly equivalent to primates. It’s not a social fish, and intelligence seems to develop from complex social interactions, although the fish is considered pretty intelligent. I mean, generally fish are not masterminds, so it’s not hard to be considered an intelligent fish, but the elephantnose fish has the brainpower to pull it off.

The elephantnose fish lives along the bottom of rivers and ponds, usually murky ones, and is mostly nocturnal. For a long time researchers thought it probably couldn’t see very well. It turns out, though, that it sees extremely well. Its retina is made up of cup-shaped cells that act like tiny mirrors, reflecting light and concentrating it so it can see better even in low light.

The elephantnose fish is a popular pet, but it is hard to keep. You have to really know what you’re doing and have a really big aquarium that’s set up just right. The males are aggressive toward each other and while the fish isn’t threatened in the wild, from what I could find out it has never bred in captivity.

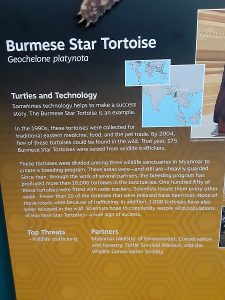

Speaking of breeding in captivity, our other animal this week isn’t a fish but a reptile. It’s called the Burmese star tortoise and unlike the elephantnose fish, it’s critically threatened in the wild. It also doesn’t have a Schauzenorgan and instead just has a short little snub nose and lives on land in dry forests in Myanmar. It’s basically the opposite of the elephantnose fish.

It gets the name star tortoise because of its pretty shell markings that look sort of like stars. It can grow up to a foot long, or 30 cm, and eats grass, fruit, and other plant material, but will also eat mushrooms, insects, and snails. It has a steeply domed carapace, the proper name for its shell, with big bumps on it. It lives in central Myanmar in south Asia, but by the late 1990s it was almost extinct in the wild. The tortoise was eaten by locals, but mostly it was captured and sold as a pet or as a medicine ingredient even though it’s a tortoise, not a medicine. This was despite the tortoise being a protected species in the country.

Conservationists realized they had to act fast before this lovely tortoise went extinct. In 2004, authorities caught smugglers with 175 of the tortoises, so Myanmar’s conservation group created tortoise breeding facilities within three of the country’s wildlife sanctuaries. They consulted zoo veterinarians and tortoise experts from all over the world to make sure the rescued tortoises were as happy and healthy as possible. The first captive-bred Burmese star tortoise babies had only been hatched the year before, since it’s hard to breed in captivity.

Each sanctuary has guards that protect it from anyone who wants to sneak in and steal the animals to sell, and 150 of the tortoises have little radio trackers attached to their shells so conservationists can keep an eye on exactly where they are. They go out and check on the tagged tortoises every other week.

Since 2004, over 16,000 Burmese star tortoises have hatched in captivity and about a thousand have been returned to the wild. They’d release more into the wild, but the conservationists are worried that poachers would collect them to sell. The country of Myanmar is in a long-running civil war, unfortunately, and that makes it hard for the people living there to concentrate on conservation. Their main goal is just to stay safe. Hopefully things will get better soon for the people of Myanmar, and when they do, the tortoises will be waiting.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!