Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 14:27 — 16.5MB)

Sign up for our mailing list! We also have t-shirts and mugs with our logo!

Thanks to Pranav and Max for their suggestions. Let’s learn about some mystery crocodiles (and crocodile mysteries) this week!

Further reading:

Huge prehistoric croc ‘river boss’ prowled waterways

Extinct “horned” crocodile’s ancestry revealed

New species of crocodile discovered in museum collections

Rediscovery of “Lost” Caiman Leads to New Crocodilian Mystery

The Orange Cave-Dwelling Crocodiles

The horned crocodile’s fossil skull:

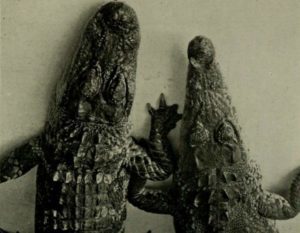

A baby Apaporis River caiman, looking fierce but cute (picture from link above):

An orange crocodile (later released, picture from link above):

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw. We’ve got a crocodile episode this week you can really sink your teeth into. Thanks to Pranav and Max for their suggestions! (Yes, I do have a cold but hopefully I don’t sound too bad. I got a covid test today to make sure it’s just a cold, and it’s just a cold.)

We talked about crododilians in episode 85, so if you want to learn more about the saltwater crocodile or how to tell the American crocodile from the American alligator and so forth, that’s the episode to listen to. This episode is going to talk about mystery crocodiles!

The partial skull of a massive extinct crocodilian discovered in Queensland, Australia over a century ago was finally described in June of 2021. All we have is the partial skull from an animal that lived between 2 and 5 million years ago, but researchers can estimate the size of the whole animal by comparing the dimensions of its skull with its closest living relation. That happens to be an animal called the false gharial that lives on a few islands in South Asia, including Java and Sumatra. It’s the only living member of the subfamily Tomistominae, which used to be common worldwide. The false gharial can grow as long as 16 feet, or 5 meters, but its extinct Australian cousin was much bigger. The new species, Gunggamarandu maunala, may have grown up to 23 feet long, or 7 meters.

A smaller extinct crocodile, called the horned crocodile, lived in Madagascar until only about 1,400 years ago. It grew a little over 16 feet long, or 5 meters. It had two projections at the back of its head that look like horns, although they weren’t actually horns and probably weren’t all that big or noticeable when the crocodile was alive.

Like Gunggamarandu, the horned crocodile’s fossils were discovered almost 150 years ago but only definitively described in 2021. In this case, though, the delay was because no one could decide where the horned crocodile belonged in the crocodilian family tree. The Nile crocodile lives on Madagascar now, and some researchers assumed that the horned crocodile was either a close relation of the Nile croc or its ancestor. Since new evidence points to the Nile crocodile being a fairly recent arrival to the island, that’s not likely, so researchers analyzed the fossil remains and reclassified the horned croc as a member of the dwarf crocodiles in 2007. Finally, though, a research team analyzed the horned croc’s DNA and determined that it belongs in its own genus and is most closely related to the ancestral species of all living crocodiles. This suggests that crocodiles evolved in Africa and spread throughout the world from there.

Researchers aren’t sure what caused the horned croc to go extinct, but it may have been a combination of factors, including a drying climate on Madagascar, the arrival of humans, and the arrival of the Nile crocodile.

Speaking of the Nile crocodile and DNA, a 2011 genetic study of the Nile crocodile resulted in a surprising discovery. The study tested not just DNA samples gathered from 123 living Nile crocodiles but from 57 crocodiles mummified in ancient Egypt. The goal was to see if there were differences between modern crocodiles and ones that lived several thousand years ago, and to determine whether maybe there was a subspecies of Nile crocodile that hadn’t been recognized by science. Instead, they discovered that what was previously known as the Nile crocodile is actually two completely different species!

The Nile croc lives in Africa and is a large, aggressive animal that can grow just over 19 feet long, or almost 6 meters. The West African croc also lives in Africa and is a smaller, less aggressive animal that can grow up to 13 feet long, or 4 meters. Since crocodiles of all species show a lot of variation in size and appearance, no one realized until 2011 that there were two species living near each other. They’re not even all that closely related.

After the finding was published, zoos across the world tested their crocodiles and discovered that a lot of their Nile crocs are actually West African crocs.

Something similar happened more recently, in 2019, when a team of scientists did a genetic study of the New Guinea crocodile. They gathered DNA from 51 museum specimens from 7 different museums, and compared them to living New Guinea crocodiles. They were hoping to determine if there are actually two species of crocodile living in different parts of New Guinea, which had been suspected for a while. It turns out that yes, there are two separate species! Knowing exactly what kinds of animals live in a particular environment helps conservationists protect them properly.

In 1952 a subspecies of the spectacled caiman was discovered by science, called the Apaporis River caiman. It lives in Colombia, South America and is relatively small as crocs go, maybe 8 feet long at most, or 2.5 meters. After that, though, it wasn’t seen again. This was partly due to how remote and hard to navigate its habitat is, and partly due to a dangerous political situation, with rebel forces occupying the jungle where the crocodiles live. A peace treaty signed in 2016 made it safe for scientists to travel to that area at last, and a Colombian biologist named Sergio Balaguera-Reina visited with various indigenous tribes of the area to ask about the Apaporis caiman and learn everything they knew about it.

At night, he and two local people paddled upriver in a canoe and searched for the caimans—and he found lots of them. He caught as many as he could to take DNA samples before releasing them again. When he got home, he tested the DNA and made a surprising discovery. Even though the Apaporis caimans look very different from another subspecies of spectacled caiman found in other parts of South America, their DNA is quite similar. That means the differences, especially the Apaporis caiman’s much narrower snout, are due to selective pressures in its environment. Balaguera-Reina is working on figuring out the causes of the Apaporis caiman’s physical differences.

The Siamese crocodile was once common throughout South Asia, but habitat loss has had a major impact on the species and for a long time it was thought to be extinct in the wild. It grows up to 13 feet long at most, or 4 meters, and is not very aggressive. It’s kept in captivity in crocodile farms, where it’s bred and killed for its meat and skin, but a lot of those farms have multiple species of closely related crocodiles and they can and do interbreed, meaning that the Siamese crocodiles in the farms are most likely hybrid animals.

In 2001 a team of conservationists traveled to Thailand to search for tigers, and one of their camera traps recorded a Siamese crocodile just walking along the river like it was no big deal. The photograph was especially lucky because it shouldn’t have even happened. The camera traps used actual film, not digital cameras which were still expensive and not very good back then. The rolls of film could capture 36 pictures before the film ran out, but the crocodile appeared on the 37th picture. Film is manufactured in long strips, then cut into pieces and rolled up and put in little canisters for a photographer to put in the camera, and the roll is a little longer than it needs to be because the ends have to be anchored in place. This particular strip of film just happened to be long enough to take 37 pictures instead of 36. If it hadn’t been, the conservationists wouldn’t have known the crocodile was still alive.

A follow-up expedition to look specifically for crocodiles discovered more of them. Since then a captive breeding program was set up, and in 2013 the first hatchlings were released into the wild.

Sometimes when a crocodile is killed, interesting things turn up in its stomach. This is what happened in 2019 when a crocodile farm in Queensland, Australia necropsied one of their saltwater crocs to see what he had died of. The croc was over 15 feet long, or 4.7 meters, and was about 60 years old. When they opened up his stomach, they found a piece of metal and six screws, the kind of metal called an orthopedic plate. It’s used to join two pieces of broken bone or strengthen an injured bone so it won’t break.

Medical devices like this are always etched with a serial number, but the metal was inside the croc’s belly for so long that the serial number was corroded off by stomach acid. This would have taken decades to happen, so the crocodile had to have eaten the metal decades ago, possibly as long as 40 years ago.

The farm contacted the police but so far they haven’t been able to trace what might have happened. The croc wasn’t bred on a farm but had been caught wild. The farm owner sent pictures of the plate to a surgeon, who determined that yes, it was probably from a human, not an animal, and that it looks like a type of plate used in Europe. The farm owner hopes the discovery will one day help solve a missing persons case.

Let’s finish with an interesting discovery in the rainforests of Gabon, a small country on the west coast of central Africa. The Abanda caves in the area are extensive, not very well explored, and full of bats and insects. A man named Olivier Testa, a professional explorer who often leads scientific expeditions into remote areas, heard a rumor about a population of orange [I read this as strange instead of orange and was too lazy to fix it] crocodiles living in the cave system. A lot of people would have just laughed, because everyone knows crocs and other reptiles like hot weather, sunshine, and warm water to hunt in. But when Testa got the opportunity to join an expedition into the cave system in 2010, he remembered the crocodiles.

Guess what they found in the cave. I bet you all guessed correctly. There really were crocodiles in the caves, specifically African dwarf crocodiles, and the biggest ones did look slightly orangey in color. Crocs don’t live in caves, but there they were. The following year the expedition returned, and this time they were there to find out more about the crocs.

A crocodile expert named Matthew Shirley came along, and he figured out why the crocodiles were in the cave. There are an estimated 50,000 bats living in the cave system, so many that the crocodiles could basically just reach up and snap bats off the walls to eat. There are lots of crickets in the cave too, and young crocs eat lots of insects.

As for the orange color of the older crocs, that comes from the water in the cave. Bats have to pee just like every other animal does, and where they roost over the water they pee into the water, naturally. So much bat urine actually has an effect on the water composition, turning it extremely alkaline. This affects the skin color of animals that stay in it for a long time, as the older crocs have.

The cave crocodiles appear to spend the dry season in the caves, eating bats and avoiding humans who hunt crocs. During the rainy season, they emerge from the caves to mate and lay their eggs in rotting vegetation outside.

This is the first population of crocodiles ever found that spends time in caves deliberately. Some researchers speculate that the crocodiles could eventually evolve into a new subspecies of dwarf crocodile that’s especially adapted to the cave system.

You know what we call those? We call them dragons.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!