Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 12:13 — 13.9MB)

Sign up for our mailing list! We also have t-shirts and mugs with our logo!

Thanks to Ethan and Simon this week for their suggestions! This week we’re looking at some extinct reptiles that each have a little something extra (and unexpected).

Further reading:

Two Extinct Flying Reptiles Compared

Cretaceous ‘Four-Limbed Snake’ Turns Out To Be Long-Bodied Lizard

Kuehneosaurids may have resembled big Draco lizards although they weren’t related:

Big turtle:

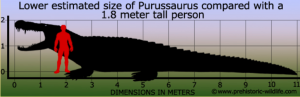

Purussaurus was big enough to eat even really big turtles (from Prehistoric Wildlife):

Meiolania had a pointy head and a pointy tail:

Not a snake with legs after all:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’ll learn about an extinct reptile suggested by Ethan, some extinct turtles suggested by Simon, and an extinct snake that might not be a snake at all. All these animals had physical details you wouldn’t expect, as we’ll see.

First, though, a reminder that I have five Kickstarter backers who haven’t sent me their birthday shout-out names and birthdays yet! I sent messages to them last month and haven’t heard back, so if you backed the Kickstarter and added on the birthday shout-out, but never got the opportunity to send me your names and birthdays, please message me as soon as possible! The shout-outs start in January!

So, on to the extinct reptiles that each have something a little extra. Let’s start with Ethan’s suggestion, the kuehneosaurids. Kuehneosaurus, kuehneosuchus, and their relations lived around 225 million years ago in what is now England. The first dinosaurs lived around the same time but kuehneosaurids weren’t dinosaurs. They were lizard-like reptiles that grew about two feet long, or 70 cm, including a long tail, and probably lived in trees and ate insects. Oh, and they had wings.

They weren’t technically wings but extended ribs. Kuehneosaurus’s wings weren’t all that big, although they were big enough that they could act as a parachute if the animal fell or jumped from a branch. Kuehneosuchus’s wings were much longer. In a study published in 2008, a team of scientists built models of kuehneosuchus and tested them in a wind tunnel used for aerospace engineering. It turned out to be quite stable in the air and could probably glide very well.

We don’t know a whole lot about the kuehneosaurids because we haven’t found all that many fossils. We’re not even sure if the two species are closely related or not. We’re not even sure they’re not the same species. Individuals of both were uncovered in caves near Bristol in the 1950s, and some researchers speculate they were males and females of the same species. Despite the difference in wings, otherwise they’re extremely similar in a lot of ways.

Generally, researchers compare the kuehneosaurids to modern Draco lizards, which we talked about in episode 237, even though they’re not related. Draco lizards are much smaller, only about 8 inches long including the tail, or 20 cm, and live throughout much of southeastern Asia. They have elongated ribs that they use to glide efficiently from tree to tree, and they eat insects. Draco lizards can fold their wings down and extend them, which isn’t something the kuehneosaurids appear to have been able to do.

Next, let’s look at Simon’s turtles. Stupendemys geographicus lived a lot more recently than the kuehneosaurids, only about 6 million years ago in northern South America. It was a freshwater turtle the size of a car: 13 feet long, or 4 meters. As if that wasn’t impressive enough, the males also had horns—but not on their heads. The male Stupendemys had projections on its shell, one on either side of its neck, that pointed forward and were probably covered with keratin sheaths to make them sharper and stronger. Males used these horns to fight each other, and we know because some of Stupendemys’s living relations do the same thing, although no living species actually have horns like Stupendemys. They’re called side-necked turtles and most live in South America, although they were once much more widespread.

Stupendemys probably grew to such a huge size because there were so many huge predators in its habitat. It lived in slow-moving rivers and wetlands, where it probably spent a lot of time at the river’s bottom eating plants, worms, crustaceans, and anything else it could find. It was too big and heavy to move very fast, but a full-grown turtle was a really big mouthful even for the biggest predator in the rivers at the time, Purussaurus.

Purussaurus was a genus of caiman, related to crocodiles, that might have grown up to 41 feet long, or 12.5 meters. We don’t know for sure since the only Purussaurus fossils found so far are skulls. It ate anything it could catch, and we even have Stupendemys fossils with tooth marks that show that Purussaurus sometimes ate giant turtles too. One Stupendemys fossil has a 2-inch, or 5 cm, crocodile tooth embedded in it.

Stupendemys is the largest freshwater turtle known and the second-largest turtle that ever lived. Only Archelon was bigger, up to about 15 feet long, or 4.6 meters. Archelon was a marine turtle that lived around 70 million years ago. We talked about it in episode 75.

Simon also told me about another turtle genus, Meiolania, which lived in what is now Australia and parts of Asia around 15 million years ago. It might even have remained in some areas as recently as 11,000 years ago. The shell, or carapace, of the largest species grew over 6.5 feet long, or 2 meters. Even the smallest species had a carapace over 2 feet long, or about 70 cm. Since the fossils of smaller species have only been found on islands, researchers think the small size may have been due to island dwarfism. It probably lived on land and ate plants. It also had horns, but not on its shell. These horns were actually on its head, although they aren’t technically horns.

The horn-like projections pointed sideways and its tail also had spikes at its end. That meant it couldn’t pull its head under its shell to protect it like most other turtles can, but on the other hand, anything that tried to bite its head or tail would get a painful mouthful of spikes.

We don’t know a whole lot about Meiolania, including if it’s related to living species of turtle. When the first fossils were found, early paleontologists thought they were lizards, not turtles. What we do know, though, is that people ate them. Bones of some species appear in the middens, or trash sites, of ancient people in Australia, and there’s evidence that they were hunted to extinction within a few hundred years after humans settled where the turtles lived. That would also explain why the island-dwelling species seemed to have lived longer than the mainland species, since people didn’t live on the islands where they’ve been found.

Finally, we’ll finish with Tetrapodophis amplectus, leading to the philosophical question about whether a snake with legs is really a snake. That’s the same question researchers were asking themselves too until very recently. Tetrapodophis was only described in 2015 and was initially determined to be an early snake that had four legs.

Tetrapodophis lived around 120 million years ago in what is now Brazil in South America. It grew about a foot long, or 30 cm, and had a slender, elongated body with small but well-developed legs. Is it a lizard with snake-like characteristics or an early snake that hadn’t completely lost its legs yet?

It had hooked teeth and we know it ate small animals because one specimen actually has the fossilized remains of its last meal in its fossilized digestive system. Initially researchers thought it might have been a burrowing animal, using its small legs to help it grab onto items and push itself forward.

The type specimen was a complete skeleton, which is really rare. Unfortunately it was illegally exported and the paleontologist who described the species didn’t bother to at least invite a Brazilian paleontologist to study the Brazilian fossil. He was also incredibly rude when asked about it so I’m not going to give you his name, but he seems to be a really sketchy guy, which is too bad.

He also made some mistakes that might not have been mistakes. If a person is dishonest in one area, they’re probably dishonest in other areas too. When he described Tetrapodophis, he mischaracterized some aspects of its anatomy to make it seem more snake-like. A new study published in November 2021 corrects those mistakes and determines that instead of being a flashy exciting snake with legs, Tetrapodophis was most likely just a small member of the lizard family Dolichosauridae. I’m happy to report, by the way, that one of the lead authors of the new study is named Tiago Simões, a paleontologist from Brazil.

Dolichosaurs were marine lizards with small legs and snake-like bodies and were actually pretty closely related to mosasaurs. You know, the marine reptiles that lived at the same time as dinosaurs and could grow more than 50 feet long in some species, or 15 meters.

There’s some controversy in the mosasaur camp too, because some researchers think mosasaurs were most closely related to snakes while others think they were most closely related to monitor lizards. It just goes to show that scientific knowledge is forever growing and adapting to new information as it comes to light, but that answers aren’t always clear.

What is clear is that extinct reptiles are awesome, but you probably already knew that.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!