Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 15:18 — 16.7MB)

Monster month is upon us, October, where all our episodes are about spooky things! This episode is only a little bit spooky, though. I give it one ghost out of a possible five ghosts on the spooky scale.

Happy birthday to Casey R.!

Further reading:

All you ever wanted to know about the “Cuero”

Mystery Creatures of China by David C. Xu

Freshwater stingrays chew their food just like a goat

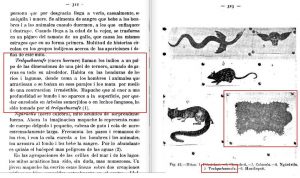

A 1908 drawing of the hide (in the red box) [picture taken from first link above]:

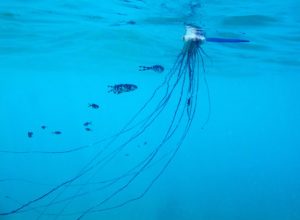

The Caribbean whiptail stingray actually lives in the ocean even though it’s related to river stingrays:

The short-tailed river stingray lives in rivers in South America and is large. Look, there’s Jeremy Wade with one!

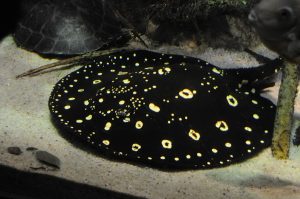

The bigtooth river stingray is awfully pretty:

Asia’s giant freshwater stingray is indeed giant:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

It’s finally October, and you know what that means. Monster month! We have five Mondays in October this year, including Halloween itself—and, in the most amazing twist of fate, our 300th episode falls on Halloween!

I know some of our listeners don’t like the really spooky episodes because they’re too scary, especially for our younger listeners. To help people out, I’m going to rate this year’s monster month episodes on a scale of one ghost, meaning it’s only a little tiny bit spooky, to five ghosts, which means really spooky. This week’s episode is rated one ghost, so it’s interesting but won’t make you need to sleep with a night light on.

Before we get started, we have two quick announcements. Some of you may have already noticed that if you scroll all the way down in your podcast app to find the first episode of Strange Animals Podcast, it doesn’t appear. In fact, the first several episodes are missing. That’s because we actually passed the 300 episode mark several weeks ago, because of the occasional bonus episode and so forth, and podcast platforms only show the most recent 300 episodes of any podcast. That’s literally the most I can make appear. However, the early podcasts are still available for you to listen to, you’ll just have to click through to the website to find them.

Second, we have a birthday shout-out this week! A very very happy birthday to Casey R! I hope your birthday is full of all your favorite things.

Now, let’s learn about the hide of South America and the blood-sucking blanket of Asia.

The first mention of a creature called El Cuero in print comes from 1810, in a book called Essay on the Natural History of Chile by a European naturalist named Fr. Juan Ignacio Molina. In his book Molina wrote, “The locals assure that in certain Chilean lakes there is an enormous fish or dragon…which, they say, is man-eating and for this reason they abstain from swimming in the water of those lakes. But they are not in agreement the appearance that they give it: now they make it long, like a serpent with a fox head, and now almost circular, like an extended bovine hide.”

Later scholars pointed out that the reason Molina thought the locals couldn’t decide what the animal looked like was because locals were talking about two different monsters. Molina just confused them. One monster was called a fox-snake and one was the cuero, which means “cow hide” in Spanish. And it’s the hide we’re going to talk about.

During the century or so after Molina wrote his book, folklorists gathered stories and legends from the native peoples of South America, trying to record as much about the different cultures as they could before those cultures were destroyed or changed forever by European colonizers. The hide appears to be a monster primarily from the Mapuche people of Patagonia.

Most stories about the hide go something like this: a person goes into the water to wash, or maybe they have to cross the lake by swimming. The hide surfaces and folds its body around the person like a blanket, dragging them under the water, and the person is never seen again. Sometimes the monster is described as resembling a cowskin or calfskin, sometimes a goat- or sheepskin. It’s usually black or brown and sometimes is reported as having white spots, and some reports say it has hooks or thorns around its edges. It may bask at the water’s surface or in shallow water in daytime, waiting for a person or animal to come too close.

The safest way to kill a hide is to trick it into coming to the surface to catch an animal or person. When it’s close enough, people throw the branches of a cactus with really long, sharp thorns at it. The hide folds its body around the cactus pieces, which pierce it through and kill it. The least safest way to kill a hide is to make sure you’re carrying a sharp knife, and when the hide grabs you, cut your way out of its enveloping folds before you drown or are eaten.

The main suggestion, starting in 1908, was that the hide was a giant octopus that lived in freshwater and had hooks on its legs or around the edges of its mantle. The main problem with this hypothesis is that there are no known freshwater octopuses. There aren’t any freshwater squid either, another suggestion.

A much better suggestion is that the hide is actually some kind of freshwater ray. And, as it happens, there are lots of freshwater stingrays native to South America. Specifically, they’re members of the family Potamotrygonidae, river stingrays.

River stingrays are pretty much round and flat with a slender tail equipped with a venomous stinger. The round part is called a disc, and some species can grow extremely large. The largest is actually a marine species called the Caribbean whiptail stingray, which can grow about 6 1/2 feet across, or 2 meters. But the short-tailed river stingray can grow about 5 feet across, or 1.5 meters, and it lives in the Río de la Plata basin in South America. The short-tailed river stingray is dark gray or brown mottled with lighter spots, while many other river stingrays are black or dark brown with light-colored spots.

Even better for our hypothesis, river stingrays are covered with dermal denticles on their dorsal surface, more commonly called the back. Dermal denticles are also called placoid scales even though they’re not actually scales. They’re covered with enamel to make them even harder, like little teeth. If that sounds strange, consider that rays are closely related to sharks, and sharks are well known to have skin so rough that you can hurt your hand if you try to pet a shark. Please don’t try to pet a shark. Admire sharks from a safe distance like you should with any wild animal.

River stingrays don’t eat people, of course. They mostly eat fish, crustaceans, worms, insects, mollusks, and other small animals. Females are much larger than males and give birth to live young. The ray’s mouth is underneath on the bottom of the disc near the front, and it has sharp teeth. Unlike pretty much every fish known, it chews its food with little bites like a mammal, which if you think about it too much is kind of creepy.

River stingrays also don’t hunt by wrapping animals in their disc, but the disc is involved in hunting in a way. The disc is formed by the ray’s fins, which are extremely broad and encircle the center part of its body, and the disc as a whole is pretty flat. The stingray will lie on the bottom of the river until a little fish or an insect gets too close. Then it will lift the front part of its disc quickly, which sucks water under it. If you’ve ever stood up in the bathtub before the water has completely drained, you can feel the suction as your body leaves the water. Quite often, the stingray’s prey gets sucked under it with the water. The ray then drops back down, trapping the animal underneath it, and chews it up.

That doesn’t mean stingrays aren’t dangerous to humans, though. The stingray’s sting is barbed and very strong, and can cause a painful wound even without its venom. A ray often hides by burying itself in the sand or mud, and if someone steps on it by accident, the ray whips its tail up and jabs its sting into their leg.

In other words, we have a large, flat creature with little pointy denticles on its back that may be dark-colored with white spots, and it’s dangerous to people and animals. That sounds a lot like the hide. There’s just one problem with this theory.

The stingray is a tropical or temperate animal. It needs warm water to survive. Patagonia is at the extreme southern end of South America, much closer to Antarctica than to the equator. No river stingray known lives within at least 500 miles of Patagonia, or 800 km, and the Patagonian lakes where the hide is supposed to live are extremely cold even in summer.

That doesn’t mean there isn’t a stingray unknown to science living in remote areas of Patagonia, of course. Many river stingray species were only discovered in the last decade or so, some of them quite large, and there are still some undescribed species. There’s always the possibility that at least one river stingray species has become adapted to the cold but hasn’t been discovered by scientists yet. It might be endangered now or even extinct.

Or the hide might not be a real animal, just a legend inspired by the river stingrays in other parts of South America. The Mapuche people are not closely related to the other peoples of Patagonia, even though they’ve lived there for at least 2,500 years, and some archaeologists think they might have migrated to Patagonia relatively late. If they brought memories of big river stingrays from their former home north of Patagonia, the memories might have inspired stories of the hide.

On the other side of the world, in China, there’s a similar legend of a monster sometimes called the xizi. The name means “mat” but it’s also referred to as a blood-sucking blanket. It lives in rivers and other waterways, and can even slide out of the water onto land. And like the hide, it’s described as a sort of living blanket that wraps itself around people or animals that venture into the water, where it pulls them under and sucks all the blood out of them.

In the case of the blood-sucking blanket, though, it’s supposed to have sharp round suckers on its underside that it uses to stick to its victims and slurp up their blood. It varies in size, sometimes about a foot across, or 30 cm, sometimes as much as 6 1/2 feet across, or 2 meters. Sometimes it’s described as reddish, sometimes green or covered with fuzzy moss on its back.

One story is that a hunter witnessed an elephant and her calf crossing a shallow river when the calf was dragged underwater by something. The mother elephant grabbed her calf and pulled it to safety, then trampled its attacker. Once the elephants were gone, the hunter went to investigate and found a dead creature that resembled a wool blanket, with a greenish, mossy back but with big suckers underneath the size of rice bowls, sort of like an octopus’s suckers.

And there is a freshwater stingray that lives in Asia, although it isn’t closely related to the river stingrays found in South America. Most of its closest relatives live in the ocean, but the giant freshwater stingray lives in rivers in southeast Asia. It’s dark gray-brown on its back and white underneath, and it has a little pointy nose at the front of its disc. It has denticles on its back and tail just like its distant South American cousins.

It’s also enormous. A big female can grow over 7 feet across, or 2.2 meters. Its tail is long and thin with the largest spine of any stingray known, up to 15 inches long, or 38 cm. In fact, its tail is so long that if you measure the giant freshwater stingray by length including its tail, instead of by width of its disc, it can be as much as 16 feet long, or about 5 meters. Some researchers think there might be individuals out there much larger than any ever measured, possibly up to 16 feet wide. The length and thinness of the tail gives the ray its other common name, the giant freshwater whipray, because its tail looks like a whip.

Even though it’s endangered due to habitat loss and hunting, and it only lives in a few rivers in South Asia these days, the giant freshwater stingray was once much more widespread. Because stingrays have cartilaginous skeletons the same way sharks do, we don’t have very many fossils or subfossil remains except for stingray teeth and denticles, so we don’t know for sure where the giant freshwater stingray used to live. But even if it didn’t live in China, travelers who had seen one in other places might have brought stories of it to China, where it spread as a scary legend.

Or, of course, there might be another freshwater stingray in China that’s unknown to science, possibly endangered or even extinct. It might even still be around, just waiting for someone to go swimming.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!