Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 15:41 — 17.8MB)

Thanks to the Tracing Owls podcast for this week’s suggestion. I’m a guest on that podcast so make sure to check it out (but while my episode is appropriate for younger listeners, most episodes are not, so be warned).

Further reading:

Huge Hippos Roamed Britain One Million Years Ago

Kenyan fossils show evolution of hippos

A sort-of Malagasy hippo:

Actual hippo (not from Madagascar, By Muhammad Mahdi Karim – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=121282994):

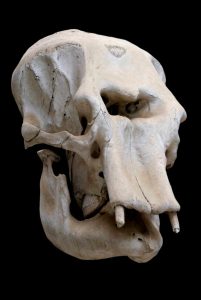

A modern hippo skull. There’s a reason the hippo is more dangerous to humans than sharks are [By Raul654 – Darkened version of Image:Hippo skull.jpg, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=242785]:

A pygmy hippo and its calf!

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to learn about a topic suggested by the host of the podcast Tracing Owls, because I’m actually a guest on that podcast in an upcoming episode! I think the episode releases later this week. I’ll put a link in the show notes, but be aware that while the podcast is interesting and often very funny, with topics that focus on weird stuff related to science, most episodes are not appropriate for younger listeners. (I think my episode should be okay.)

Several years ago now there was a movie called Madagascar, which is about a group of zoo animals that end up shipwrecked on the island of Madagascar. I love this movie, especially the lemur King Julian, but one of my favorite characters is a hippopotamus named Gloria, voiced by Jada Pinkett Smith. The island country of Madagascar is off the southeastern coast of Africa, but as we talked about in episode 77, it’s been separated from the continent of Africa for millions of years and the animals of that country have mostly evolved separately from the animals of Africa. That’s part of why the movie Madagascar is so funny, since the main characters in the movie are all native to Africa—a lion, a zebra, a giraffe, and Gloria the hippo—and don’t know anything about the animals they encounter on Madagascar. Like this guy:

[King Julian clip]

But it turns out that hippos did once live on Madagascar, and that’s what we’re going to learn about today.

We’re not sure when the first humans visited Madagascar, but it was at least 2500 years ago and possibly as much as 9500 years ago or even earlier. By 1500 years ago people were definitely living on the island. It’s likely that hunting parties would travel to Madagascar and stay there for a while, then return home with lots of food, but eventually people decided it would be a nice place to live.

Madagascar is a really big island, the fourth largest island in the world. It’s been separated from every other landmass for around 88 million years, and has been separated from Africa for about 165 million years. Many of the animals and plants that live on Madagascar are very different from the ones living anywhere else in the world as a result.

To put this into perspective, here’s your reminder that the closest living relative of the hippopotamus is the whale, and 60 million years ago the common ancestor of both hippos and whales was a small semi-aquatic animal. That was about 28 million years after Madagascar was on its own in the big wide ocean, and 105 million years after the landmass that we call Africa broke off from the supercontinent Gondwana and began moving very slowly into the position it’s in today. When Madagascar finally broke free of the landmass we now call India, dinosaurs were still the dominant land animal.

So why are there remains of small hippos on Madagascar? How did the hippos get to Madagascar and why aren’t they still around? Did the hippo originate in Africa or in some other place? So many questions!

The ancestors of modern cetaceans, which includes whales and dolphins and their close relations, are found in the fossil record about 52 million years ago, although it might have been 53 or even 54 million years ago depending on which scientist you ask. That’s when the whale side of the suborder Whippomorpha started developing separately from the hippo side. The “morpha” part of Whippomorpha just means “resembling,” and I’m happy to report that the “whippo” part is actually a combination of the words whale and hippo. Truly, it gave me great joy when I learned this fact, because I assumed “whippo” was something in Greek or Latin, or maybe referred to an animal with a whip-like tail. Nope, whale+hippo=whippo.

Anyway, while we know a fair amount about the evolution of cetaceans from their semi-aquatic ancestors, we don’t know much at all about the hippo’s evolution. There’s still a lot of controversy about whether hippos really are all that closely related to whales after all. They share a lot of similarities both physically and genetically, so they’re definitely relations, but whether they’re close cousins is less certain. The confusion is mainly due to not having enough fossils of hippopotamus ancestors.

The modern hippo, the one we’re familiar with today, usually called the common hippo, first appears in the fossil record about six million years ago. We have fossils of animals that were pretty obviously close relations to the common hippo, if not direct ancestors, that date back about 20 million years. But it’s the gap between the hypothesized shared ancestor of both hippos and cetaceans that lived around 60 million years ago, and the first ancestral hippos 20 million years ago, that is such a mystery.

What we do know, though, is that while the common hippo is native to Africa, its ancestors weren’t. Hippo relations once lived throughout Europe and Asia, and probably migrated to Africa around 35 million years ago. In fact, hippos were common throughout Eurasia until relatively recent times. In 2021, a fossilized hippopotamus tooth was found in a cave in Somerset, England that probably lived only one million years ago. That was well before humans migrated into the area, which was a good thing for the humans because this hippo was humongous. It probably weighed around 3 tons, or 3200 kg, while the common hippo is about half that on average.

This particular huge hippo, Hippopotamus antiquus, lived throughout Europe and only went extinct around 550,000 years ago as far as we know. This was during a time that Europe was a lot warmer than it is today and hippos migrated north from the Mediterranean as far as southern England. The common hippo, H. amphibius, the one still around today, also migrated back into Eurasia during this warm period and its fossilized remains have been found in parts of England too.

These days, there are only two living species of hippo, the common hippo and the pygmy hippo. We talked about the pygmy hippo briefly in episode 135, including the astonishing fact that it only grows around 3 feet tall, or 90 cm, and lives in deep forests in parts of west Africa. There also used to be some other small hippos that evolved on islands and exhibited island dwarfism, and which probably weren’t closely related to the pygmy hippo. These include the Cretan dwarf hippopotamus that lived on the Greek island of Crete until around 300,000 years ago and maybe much more recently, and the Cyprus dwarf hippopotamus that lived on the island of Cyprus until only around 10,000 years ago. The Cyprus hippo was the smallest hippo found so far, only about 2.5 feet tall, or 75 cm. There are dogs larger than that! But the small hippo we’re interested in is the Malagasy pygmy hippopotamus.

There actually wasn’t just one hippo species that lived on Madagascar. Scientists have identified three species, although this may change as more studies take place and as new remains are found. The different species probably didn’t all live on the island at the same time, and some researchers think they might have resulted from three different migrations of hippos to the island.

But how did they get to the island? Madagascar is 250 miles away from Africa, or 400 km, way too far for a hippo to swim. The Malagasy hippos were well established on the island, too, not just a few individuals who accidentally reached shore. That means there must have been some way for hippos to reach Madagascar fairly easily at different times.

The best hypothesis right now is that at times when the ocean was overall shallower than it is now, such as during the Pleistocene glaciations, there are enough small islands between Africa and Madagascar that hippos could travel between them pretty easily. Since those islands would be far underwater now, we don’t have any way to know for sure. We can’t exactly dive down and look for hippo fossils, unfortunately.

The really big question, of course, is whether any hippos still survive on Madagascar. We know they were around as recently as 1,000 years ago, because we have subfossil remains. (Just a reminder that subfossil means that the remains are either not fossilized, or only partially fossilized.) Not only that, the bones show butchering marks so we know people killed and ate the hippos. Right now scientists think the hippos were hunted to extinction by the humans who settled on Madagascar, but there’s some evidence that it happened much more recently than 1,000 years ago.

Over the last several hundred years, European colonizers of Madagascar collected stories from Malagasy natives about animals that resemble hippos. More recently, some stories have also been collected by scientists.

In 1995, a biologist named David Burney, who was studying recently extinct animals on Madagascar, interviewed some elderly residents in various villages. He wasn’t actually trying to learn about mystery animals, he was mostly just trying to find the paleontological sites scientists had found decades before. He figured the older residents would remember those scientists’ visits, and he was right. But the residents also had other stories to tell about the bones dug up by scientists. Some of them said those bones belonged to animals they had seen alive.

In one village, several different people told a story about a cow-sized animal that had occasionally entered the village at night. It was dark in color and made distinctive grunting sounds, and had large floppy ears. When some people approached it too closely, it ran back to the water and submerged.

Dr. Burney thought the residents might have seen pictures of an elephant and transferred some of its details to the mystery animal, especially the large size and floppy ears. But when he showed a picture of an elephant to them, they were clear that it wasn’t the same animal. They chose a picture of a hippo instead, but said the animal they’d seen had larger ears. Various witnesses also said the animal had a large mouth with really big teeth, that its feet were flat, and that it was the size of a cow but didn’t have horns. One man even imitated the animal’s call, which Burney reported sounded like a hippopotamus even though the man had never seen or heard a hippo.

Burney was cautious about publishing his findings, and in fact in his article he mentions that even at the time, he and his team of scientists were cautious about even pursuing information about living Malagasy hippos. They didn’t want to be seen as acting like cryptozoologists, which says a lot about how cryptozoologists conduct their research. Cryptozoology isn’t a scientific field of study despite its name. Biologists, paleontologists, and other experts research mystery animals all the time. That’s just part of their job; they don’t have to call themselves something special. It’s unfortunately common that people who call themselves cryptozoologists don’t have a scientific background and may not know how to conduct proper field research. Very often, cryptozoologists also don’t know very much about the animals that definitely exist, and how can you determine what a true mystery animal is if you don’t know about non-mystery animals?

Luckily, Dr. Burney and his team decided to pursue this particular mystery animal, along with some others they learned about. The last hippo-like animal sighting they could pin to a particular date happened in 1976. If the animal in question was a hippo, and it really was alive only about 50 years ago, it might have gone extinct since then. Or it might still be alive and hiding deep in the forests of Madagascar.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!

This is what a hippo sounds like, and you hear it all the time on this podcast because I like it:

[hippo sound]