Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 10:37 — 11.9MB)

Thanks to Vaughn and Jan for their suggestions this week! We’re going to learn about mutualism of various types.

Further reading:

The odd couple: spider-frog mutualism in the Amazon rainforest

What Birds, Coyotes, and Badgers Know About Teamwork

Octopuses punch fishes during collaborative interspecific hunting events

An Emotional Support Dog Is the Only Thing That Chills Out a Cheetah

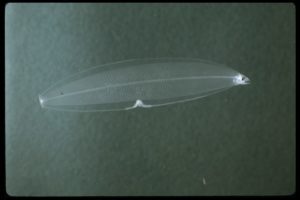

Buddies [picture from the first link above]:

The honeyguide bird:

Cheetahs and dogs can be friends:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to learn about a topic that I’ve been wanting to cover for a long time, mutualism. It’s a broad topic so we won’t try to cover everything about it in this episode, just give an overview with some examples. Vaughn suggested symbiotic behavior ages ago, and Jan gave me a great example of this, also ages ago, so thanks to both of them!

Mutualism is similar to other terms, including symbiosis, often referred to as “a symbiotic relationship.” I’m using mutualism as a general term, but if you want to learn more you’ll quickly find that there are lots of terms referring to different interspecies relationships. Basically we’re talking about two unrelated organisms interacting in a way that’s beneficial to both. This is different from commensalism, where one organism benefits and the other doesn’t but also isn’t harmed, and parasitism, where one organism benefits and the other is harmed.

We’ll start with the suggestion from Jan, who alerted me to this awesome pair of animals. Many different species have developed this relationship, but we’ll take as our specific example the dotted humming frog that lives in parts of western South America.

The dotted humming frog is a tiny nocturnal frog that barely grows more than half an inch long from snout to vent, or about 2 cm. It lives in swamps and lowland forests and spends most of the day in a burrow underground. It comes out at night to hunt insects, especially ants. It really loves ants and is considered an ant specialist. That may be why the dotted humming frog has a commensal relationship with a spider, the Colombian lesserblack tarantula.

The tarantula is a lot bigger than the frog, with its body alone almost 3 inches long, or 7 cm. Its legspan can be as much as 8 and a half inches across, or 22 cm. It’s also nocturnal and spends the day in its burrow, coming out at night to hunt insects and other small animals, although not ants. It’s after bigger prey, including small frogs. But it doesn’t eat the dotted humming frog. One or even more of the frogs actually lives in the same burrow as the tarantula and they come out to hunt in the evenings at the same time as their spider roommate.

So what’s going on? Obviously the frog gains protection from predators by buddying up with a tarantula, but why doesn’t the tarantula just eat the frog? Scientists aren’t sure, but the best guess is that the frog protects the spider’s eggs from ants. Ants like to eat invertebrate eggs, but the dotted humming frog likes to eat ants, and as it happens the female Colombian lesserblack tarantula is especially maternal. She lays about 100 eggs and carries them around in an egg sac. When the babies hatch, they live with their mother for up to a year, sharing food and burrow space.

This particular tarantula also gets along with another species of frog that also eats a lot of ants. Researchers think the spiders distinguish the frogs by smell. The ant-eating frogs apparently smell like friends, or at least useful roommates, while all other frogs smell like food. Or, of course, it’s possible that the ant-eating frogs smell and taste bad to the spider. Either way, both the frogs and the tarantulas benefit from the relationship–and this pairing of tiny frogs and big spiders is one that’s actually quite common throughout the world.

Mutualism is everywhere, from insects gathering nectar to eat while pollenating flowers at the same time, to cleaner fish eating parasites from bigger fish, to birds eating fruit and pooping out seeds that then germinate with a little extra fertilizer. Many mutualistic relationships aren’t obvious to us as humans until we’ve done a lot of careful observations, which is why it’s so important to protect not just a particular species of animal but its entire ecosystem. We don’t always know what other animals and plants that animal depends on to survive, and vice versa.

Sometimes an individual animal will work together with an individual of another species to find food. This may not happen all the time, just when circumstances are right. Sometimes, for example, a coyote will pair up with a badger to hunt. The coyote is closely related to wolves and can run really fast, while the American badger can dig really fast. Both are native to North America. They also both really like to eat prairie dogs, a type of rodent that can run really fast and lives in a burrow. Some prairie dog tunnels can extend more than 30 feet, or 10 meters, with multiple exits. The badger can dig into the burrow and if the prairie dog leaves through one of the exits, the coyote chases after it. When one of the predators catches the prairie dog, they don’t share the meal but they will often continue to hunt together until both are able to eat.

Other animals hunt together too. Moray eels will sometime pair up with a fish called the grouper in a similar way as the coyote and badger. The grouper is a fast swimmer while the eel can wriggle into crevices in rocks or coral. The grouper will swim up to the eel and shake its head rapidly to initiate a hunt, and if the grouper has seen a prey item disappear into a crevice, it will lead the eel to the crevice and shake its head at it again.

Groupers also sometimes pair up with octopuses to hunt together, as will some other species of fish. Like the eel, the octopus can enter crevices to chase an animal that’s trying to hide. But the octopus isn’t always a good hunting partner, because if the grouper catches a fish, sometimes the octopus will punch the grouper and steal its fish. Not cool, octopus.

Birds have mutualistic relationships too, including the honeyguide that lives in parts of Africa and Asia. It’s a little perching bird that’s mostly gray and white or brown and white, with the males of some species having yellow markings. It eats insects, spiders, and other invertebrates, and it especially likes bee larvae. But it’s just a little bird and can’t break open wild honeybee hives by itself.

Some species of honeyguide that live in Africa have figured out that humans can break open beehives. When the honeyguide bird finds a beehive, it will fly around until it hears the local people’s hunting calls. The bird will then respond with a distinct call of its own, alerting the people, and will guide them to the beehive. This has been going on for thousands of years. The humans gather the honey, the honeyguide feasts on the bee larvae and wax, and everyone has a good day except the bees.

The honeyguide is also supposed to guide the honey badger to beehives, but there’s no definitive evidence that this actually happens. Honey badgers do like to eat honey and bee larvae, though, and when a honey badger breaks open a beehive, honeyguides and other birds will wait until it’s eaten what it wants and will then pick through the wreckage for any food the badger missed. But the honeyguide might lead the honey badger to the hive, we just don’t know for sure.

Humans sometimes even help other animals into a commensal relationship. Vaughn gave me an example of a cheetah in a zoo who became best friends with a dog. This hasn’t just happened once, it’s happened lots of times because zookeepers have found that it helps cheetahs kept in captivity. Cheetahs are social animals but sometimes a zoo doesn’t have a good companion for a cheetah cub. The cub could be in danger from older, unrelated cheetahs, but a cheetah all on its own is prone to anxiety. It’s so important for a cheetah to have a sibling that if a mother cheetah only has one cub, or if all but one cub dies, a lot of times she’ll abandon the single cub. If this happens in the wild, it’s sad, but if it happens in captivity the zoo needs to help the cub.

To do this, the zoo will pair the cub with a puppy of a sociable, large breed of dog, such as a Labrador or golden retriever. The cub and the puppy grow up together. The cheetah has a mellow friend who helps alleviate its anxiety, and the dog has a friend who’s really good at playing chase.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!