Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 14:07 — 15.8MB)

Thanks to Will and Måns for their suggestions this week! Let’s learn about some mystery bovids, or cows and cow relations!

Further reading:

Kouprey: The Ultimate Mystery Mammal

A musk ox (top) and a wild yak (bottom):

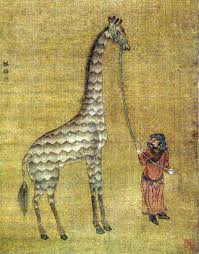

A young kouprey bull from the 1930s:

Sculpture of two grown kouprey bulls [photo by Christian Pirkl – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=73848355]:

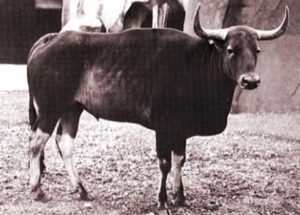

A banteng bull (with a cow behind him) [photo taken from this site]:

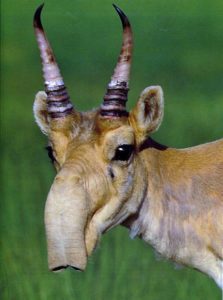

A qilin/kilin/kirin looking backwards:

The “purple” calf:

The Milka purple cow:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to learn about some mystery bovids, or cow relations, suggested by Will and Måns, whose name I am probably mispronouncing.

We’ll start with a mystery about the musk ox, which is not otherwise a mysterious animal. Måns emailed about reading a children’s book about animals that had a picture of a musk ox in the part about the Gobi Desert. The problem is, the musk ox is native to the Arctic and was once found throughout Greenland, northern Canada, Alaska, and Siberia. So the question is, was the book wrong or are there really musk oxen in the Gobi Desert?

We’ll start by learning about the musk ox and the Gobi Desert. The musk ox can stand up to 5 feet tall at the shoulder, or 1.5 meters. It has thick, dense, shaggy fur all over, a tiny tail only about four inches long, or 10 cm, and horns that curve down close to the sides of its head and then curve up again at the ends.

The musk ox is well adapted to the cold, which isn’t a surprise since it evolved during the ice ages. Its ancestors lived alongside mammoths, woolly rhinos, and other Pleistocene megafauna. Like many cold-adapted animals, its fur consists of a thick undercoat that keeps it warm, and a much longer layer of fur that protects the softer undercoat. The undercoat is so soft and so good at keeping the animal warm in bitterly cold temperatures that people will sometimes keep musk oxen in order to gather the undercoat in spring when it starts to shed, to use for making clothing and blankets. But it’s definitely not a domesticated animal. It can be aggressive and extremely dangerous.

A warm coat isn’t the musk ox’s only cold adaptation. The hemoglobin in its blood is able to function well even when it’s cold, which isn’t the case for most mammals. It lives in small herds that gather close together in really cold weather to share body heat, and if a predator threatens the herd, the adults will form a ring around the calves, their heads facing outward. Since a musk ox is huge, heavy, and can run surprisingly fast, plus it has horns, if a wolf or other predator is butted by a musk ox it might end up fatally injured.

The main predator of the musk ox is the human, who hunted it almost to extinction by the early 20th century. It was completely extirpated in Alaska but was reintroduced there and in parts of Canada in the late 20th century. Similarly, it was reintroduced to parts of Siberia and even parts of northern Europe, although not all the European introductions were successful.

So what about the Gobi Desert? It’s nowhere near the Arctic. Not all deserts are hot. A desert just has limited rainfall, and the Gobi is a cold desert. Parts of the Gobi are grasslands and parts are sandy or rocky, and it covers a huge expanse of land in central Asia, mainly divided between northern China and southern Mongolia. Some parts of it do get limited rainfall in the summer and limited snowfall and frost in the winter, but for the most part it’s dry and therefore has limited vegetation for animals to eat.

Animals do live in the Gobi, though. The wild Bactrian camel, which has two humps, is found nowhere else in the world and is critically endangered. The Mongolian wild ass lives in parts of the Gobi, as do several species of antelope and gazelle, wild sheep, and ibex. The Gobi bear, which is the rarest bear in the world, also lives in the Gobi, along with smaller animals like hares, foxes, polecats, marmots, and various lizards, snakes, and birds. Occasionally wolves and snow leopards visit parts of the Gobi. So do humans, specifically nomadic herders who travel through parts of the desert to find food for their animals.

Of all the animals found in the Gobi, and in central Asia in general, the musk ox is not listed on any scholarly site I could find. Despite its name, it’s not actually closely related to other cattle and is instead most closely related to goats and sheep. However, a close relation of the domestic cow and its ancestors is the wild yak, the ancestor of the domestic yak. The wild yak lives mostly in the Himalayas these days but was once much more widespread, and the domestic yak is farmed by nomadic herders in the colder, more mountainous parts of the Gobi.

The yak isn’t closely related to the musk ox, but it does have a very similar-looking long, shaggy coat. Its horns point forward and up like cattle horns, but to someone who doesn’t really know much about yaks or musk ox, it would be easy to get the two confused. This seems to be what has happened in the case of the children’s book Måns read and in various non-academic websites. I think we can call this mystery solved.

Next, let’s go on to Will’s suggestion of mystery bovids. The family Bovidae includes not just the domestic cow and its relations but goats, sheep, antelopes, and many other animals with cloven hooves who chew the cud as part of the digestive process–but not deer or giraffes, and not the pronghorn even though people call it an antelope. Many bovids have horns, usually only two but sometimes four or even six, and those horns are never branched. Sometimes only the male has horns, sometimes both the male and female. Bovids don’t have incisors in the front of the upper jaw, only in the lower jaw, and instead has a tough dental pad that helps it grab plants.

One mystery bovid is a creature from Madagascar, called the habeby. It’s supposed to look like a big white sheep with brown or black spots. It has cloven hooves and droopy ears but not horns, and it’s supposed to be nocturnal and never seen in the daytime. Its eyes are very large and staring. It’s shy and fortunately not dangerous. Bovids are almost always diurnal, so a nocturnal bovid would be quite unusual.

Since sheep and other bovids aren’t native to Madagascar, it’s much more likely that the habeby is a type of large lemur that looks enough like a sheep at a distance that people thought it was a sheep. Either it’s extinct now or it lives in such remote areas that it’s never seen anymore.

Another Madagascar mystery animal is called the songòmby, which either looks like a wild ox or a horse depending on the story. Like the habeby it has floppy ears, a spotted coat, and hooves. Some stories say it has a single horn, some stories say it has a pair of horns, and other stories say it has no horns at all. It lives in mountainous areas and can run incredibly fast uphill, but is much slower downhill because its long ears flop over its eyes and it has trouble seeing where it’s going. This is fortunate, because it’s also supposed to eat people.

One clue to the songòmby’s possible real identity comes from some stories that state it always looks backwards over its back, and is only ever seen from the side. This is reminiscent of how the Chinese kilin is often represented, and also explains why the songòmby has a varying number of horns and looks like a cow or horse but is supposed to eat people. The kilin is often depicted as having both hooves and fangs, and may have a single horn, a pair of horns, or no horns at all. Arab traders began stopping in Madagascar around a thousand years ago and would have brought Chinese goods, including some items decorated with kilins. It’s possible that the kilin artwork inspired the story of the songòmby, but it’s also so similar to the habeby in some ways that details of that animal may have been incorporated into the story of the songòmby, or vice versa.

Way back in episode 100 we talked briefly about an animal called the kouprey. It’s a wild ox native to southeast Asia, sometimes called the forest ox. It can stand over six feet tall at the shoulder, or two meters, and while bulls are dark brown, cows and calves are a lighter brownish-gray. Both have white lower legs with a dark stripe down the front of the front legs. The bull’s horns look like those of a domestic cow or wild yak, but are extremely large and curve forward, but the cow’s horns grow up and back, more like an antelope’s horns. As a bull ages, the tips of his horns start to fray and end up looking almost tassled. A bull also develops a large dewlap as he ages, which in older bulls can actually be so big it touches the ground.

By 1937, when a kouprey was sent to a zoo in Paris, the animal was probably mostly restricted to the forests of Cambodia. Before then it had been completely unknown to science, but after that, European big game hunters went to Cambodia to kill as many as possible. It was already rare and by the 1950s there were probably fewer than 500 individuals left alive. By the 1960s, there were probably no more than 100 animals left alive. The last verified sighting of one was in 1983.

Recently, some scientists have questioned whether the kouprey actually existed at all. Its description sounds a lot like another bovid, the wild banteng. A bull banteng is dark brown or black while the cows are light brown or reddish-brown. Both have white lower legs and a white patch on the rump. Some scientists started to think that either the kouprey was a misidentification of the banteng or the hybrid offspring of a banteng and a domestic cow.

A 2006 genetic study suggested that this was the case, that the kouprey was just a hybrid animal. But a follow-up study, including genetic testing of a kouprey skull that dated back to before cattle were domesticated, came to a different conclusion. The kouprey was a distinct species, not a hybrid animal. The real mystery now is whether it’s still alive or if it has gone extinct in the last 40 years.

We’ll finish with a domestic cow that’s a little bit of a mystery. A popular brand of chocolate in Europe is Milka, and since 1973 many of its advertisements have included a light purple and white cow with a bell around her neck. Well, in 2012 a calf was born in Serbia that actually looked like the Milka purple cow. It was a purple cow!

In January of 2012 a bull calf was born on a small farm in Serbia. There’s not a lot of information available about it, but it looks like it was a breed of cattle called the busa, or maybe a busa cross. The busa is mainly raised in the mountainous parts of Serbia and mostly raised as a meat animal. It’s rare these days but was once extremely popular in the area, so a lot of cattle raised in Serbia have at least some busa ancestry. The busa can be white with darker markings, or a solid color with no white or very little white. It can be red-brown, black, or gray.

In pictures, the purple calf’s mother looks to be black and white. The calf itself is white with markings that look pale blue-gray, almost lilac. The pictures aren’t very good so it’s hard to tell. The farmer was surprised when he saw the calf and called a veterinarian to make sure it was healthy, which it was. The veterinarian suggested the calf’s strange coloration was just a rare color mutation.

As it happens, a blue-gray coloration is common in a variety of busa cattle raised in Macedonia. It’s also a common coloration in other breeds of cattle. A pale version of this color can look almost like a shade of lilac. Since I can’t find a follow-up to the 2012 articles about the calf, it’s probable that as he grew up, his spots darkened to look more gray than purple. The farmer said that he would be keeping the little purple cow instead of slaughtering him to make steaks and hamburgers, so hopefully there’s still a handsome purple and white bull living his best life in the mountains of Serbia.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!