Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 13:19 — 14.8MB)

Thanks to Alexandra and Pranav for their suggestions this week! Let’s learn about manatees and sloths, including a surprising extinct sloth.

Further reading:

A West Indian manatee:

A three-toed sloth:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we have a suggestion from Alexandra and Pranav, who wanted an episode about manatees. We’ll also talk about another marine mammal, a weird extinct one you may never have heard of.

The manatee is also called the sea cow, because it sort of slightly resembles a cow and it grazes on plants that grow underwater. It’s a member of the order Sirenia, which includes the dugong, and sirenians are probably most closely related to the elephant. This sounds ridiculous at first, but there are a lot of physical similarities between the manatee and the elephant. Their teeth are very similar, for instance, even if the manatee doesn’t grow tusks. The elephant has a pair of big chewing teeth on each side of its mouth that look more like the bottoms of running shoes than ordinary teeth. Every so many years, the four molars in an elephant’s mouth start to get pushed out by four new molars. The new teeth grow in at the back of the mouth and start moving forward, pushing the old molars farther forward until they fall out. The manatee has this same type of tooth replacement, although its teeth aren’t as gigantic as the elephant’s teeth. The manatee also has hard ridged pads on the roof of its mouth that help it chew its food.

Female manatees are larger than males on average, and a really big female manatee can grow over 15 feet long, or 4.6 meters. Most manatees are between 9 and 10 feet long, or a little less than 3 meters. Its body is elongated like a whale, but unlike a whale it’s slow, usually only swimming about as fast as a human can swim. Its skin is gray or brown although often it has algae growing on it that helps camouflage it. The end of the manatee’s tail looks like a rounded paddle, and it has front flippers but no rear limbs. Its face is rounded with a prehensile upper lip covered with bristly whiskers, which it uses to find and gather water plants.

Every so often a manatee will eat a little fish, apparently on purpose. Since most herbivorous animals will eat meat every so often, this isn’t unusual. Mostly, though, the manatee spends almost all of its time awake eating plants, often from the bottom of the waterway where it lives. It lives in shallow water and will use its flippers to walk itself along the bottom, and also uses its flippers to dig up plants. Its upper lip is divided in two like the upper lips of many animals, which you can see in a dog or cat as that little line connecting the bottom of the nose to the upper lip. In the manatee, though, both sides of the lips have a lot of muscles and can move independently.

There are three species of manatee alive today: the West Indian manatee that lives in the Gulf of Mexico down to the eastern coast of northern South America, the Amazonian manatee that lives exclusively in fresh water in the Amazon basin, and the West African manatee that lives in brackish and fresh water. Sometimes the West Indian manatee will also move into river systems to find food.

Back in episode 153 we talked about the Florida manatee, which is a subspecies of West Indian manatee. In the winter it mostly lives around Florida but in summer many individuals travel widely. It’s sometimes found as far north as Massachusetts along the Atlantic coast, and as far west as Texas in the Gulf of Mexico, but despite its size, the manatee doesn’t have a lot of blubber or fat to keep it warm. The farther away it travels from warm water, the more likely it is to die of cold.

In the 1970s there were only a few hundred Florida manatees alive and it nearly went extinct. It was listed as an endangered species and after a lot of effort by a lot of different conservation groups, it’s now only considered threatened, but it’s still vulnerable to habitat loss, injuries from boats, and getting tangled in fishing gear and drowning. Occasionally a crocodile will eat a young manatee, but for the most part it’s so big, and lives in such shallow water, that most predators won’t bother it. It basically only has to worry about humans, and unfortunately humans still cause a lot of manatee deaths every year with boats.

A lot of times, a manatee that’s hit by a boat is only injured. There are several rehabilitation centers in the United States, where an injured manatee can be treated by veterinarians until it’s healed and can be reintroduced into the wild.

One other detail that makes the manatee similar to the elephant is its flippers, which is probably not what you expected me to say. Most manatees have toenails on their flippers that closely resemble the nails on elephant feet. The exception is the Amazonian manatee that doesn’t have toenails at all.

A lot of the food the Amazonian manatee eats actually floats on the surface of the rivers where it lives, and it will also eat fruit that drops into the water. Because the Amazon basin is subject to a dry season where there’s not a lot of food, the manatee eats a lot when it can to build up fat reserves for later. During the dry season, it usually moves to the biggest lakes in the area as the rivers and shallower lakes dry up or get too shallow for the manatee to swim in. Since the manatee has a low metabolic rate, it can live off its fat reserves until the dry season is over.

One interesting thing about the manatee is that it only has six vertebrae in its neck. Almost all other mammals have seven, even giraffes. The exception is the two-toed sloth, which also has six, and the three-toed sloth, which has a varying number of neck vertebrae, up to nine in some species!

Pranav also wanted to learn about sloths, so let’s talk about them next. All sloths are native to Central and South America. The sloths living today live in forests, especially rainforests, and spend almost all their time in trees.

A sloth makes the manatee look like a speed demon. It spends most of its time hanging from its long claws beneath branches, eating leaves and other plant material, but when it does move, it does so extremely slowly. This helps it stay camouflaged from predators, because its fur contains algae that makes it look green, so a barely-moving green-furred sloth hanging from a tree just looks like a bunch of leaves. It does move from one tree to another to find fresh leaves, and once a week it climbs down from its tree to defecate and urinate on the ground. Yes, it only relieves itself once a week.

The sloth’s digestive tract is also extremely slow, which allows it to extract as much nutrition as possible from each leaf. It takes about a month for a sloth to fully digest one mouthful of food.

The three-toed sloth is about the size of a large cat while the two-toed sloth is slightly larger, maybe the size of a small to medium-sized dog. The two-toed sloth is nocturnal while the three-toed sloth is mostly diurnal. Even though they look and act very similar, the two types of sloth are not very closely related. Both have long curved claws and strong pulling muscles, although their pushing muscles are weak. This is why a sloth can’t walk like other animals; the muscles that would allow it to do so aren’t strong enough to support its own weight. And yet, it can hang from a branch and walk along it for as long as it needs to. I don’t think I could hang from a branch by my fingers for five minutes without having to let go.

Surprisingly, the sloth can also swim quite well, which allows it to find new trees even if there are streams or rivers in the way. But a few million years ago, a different type of sloth lived off the coast of western South America and did a whole lot of swimming. In fact, later species of Thalassocnus were probably fully marine mammals.

We talked about Thalassocnus briefly way back in episode 22. It was related to the giant ground sloths that were themselves related to the living three-toed sloths. The earliest Thalassocnus fossils are of semi-aquatic animals that grazed in shallow water. Fossils from more recent species show increasing adaptations to deeper water, including increased weight of the skeleton to help it stay underwater instead of bobbing up to the surface.

Thalassocnus eventually evolved a stiff, partially fused spine, which reflects the unusual way it moved around underwater. Instead of swimming the way a whale does, or even the way a dog or person does, it moved more like a hippopotamus. Hippos sort of bounce along underwater, using their feet to push off from the bottom. Thalassocnus probably did this too and used its long tail to help it maneuver.

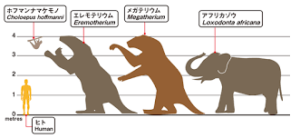

Thalassocnus was a lot bigger than modern sloths. Even the smallest known species were the size of a big human, and the biggest species grew up to 11 feet long, or 3.3 meters. That biggest species was the one that lived most recently, up to about 1.5 million years ago, and researchers think it was fully aquatic. Its nostrils were on the top of its snout and it had prehensile lips to help it find plants underwater. Some researchers even think it could have had a short trunk something like a tapir. It had seven neck vertebrae, as in most other mammals.

There’s still a lot we don’t know about Thalassocnus, but because we have fossils of five different species that lived at different times, scientists are able to determine a lot about how it developed from a mostly terrestrial animal to a mostly or fully marine animal. The youngest species had smaller, weaker legs than the earlier ones, which suggests it didn’t use its legs to walk on land. It probably lived a lot like modern manatees, finding sea grasses and other plants on the sea floor in shallow water, but not able to swim very fast.

One last thing about the manatee is that it spends about half of its time asleep, and it sleeps underwater. It comes up for a breath every 15 minutes or so. Modern sloths sleep a lot too, around 15 hours a day. Chill sleepy friends.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!