Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 12:23 — 13.8MB)

Thanks to Murilo for suggesting this week’s episode about the sawfish and the sawshark!

Further Reading:

Two New Species of Sixgill Sawsharks Discovered

Do not step:

The underside of a largetooth sawfish [photo by J. Patrick Fischer – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17421638]:

The sawshark has big eyes [photo by OpenCago.info – Wikimedia Commons [1], CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=25240095]:

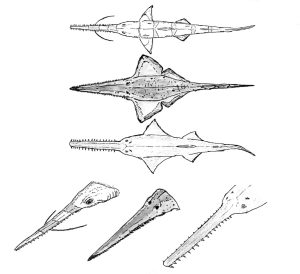

A comparison of rostrums. The sawskate is in the middle, the one with barbels is the sawshark, and the really toothy one is the sawfish [picture by Daeng Dino – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=137983599]:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to learn about an amazing fish suggested by Murilo. It’s the sawfish, and while we’re at it, we’re also going to learn about a different fish called the sawshark.

There are five species of sawfish alive today in two genera, and they’re all big. The smallest species can still grow over 10 feet long, or 3 meters, while the biggest species can grow over 20 feet long, or 6 meters. The largest sawfish ever reliably measured was 24 feet long, or 7.3 meters. Since all species of sawfish are endangered due to overfishing, pollution, and habitat loss, really big individuals are much rarer these days.

The sawfish lives mostly in warm, shallow ocean waters, usually where the bottom is muddy or sandy. It can also tolerate brackish and even freshwater, and will sometimes swim into rivers and live there just fine. The largetooth sawfish is especially happy in freshwater.

Let’s talk specifically about the largetooth sawfish for a moment, since we know the most about it. Like other sawfish, the female gives birth to live young, up to 13 babies at a time, and the babies can be up to three feet long at birth, or 90 cm. When a baby is born, its saw, which we’ll talk about in a minute, is covered with a jelly-like sheath that keeps it from hurting its mother. The sheath dissolves soon after birth.

The mother usually gives birth around the mouth of a river, and instead of swimming into the ocean, the babies swim upstream into the river. They live there for the next several years, and some individuals and even some populations may live their whole lives in the river. It’s sometimes called the river sawfish or the freshwater sawfish for this reason.

One interesting thing about the largetooth sawfish is how agile it is. All sawfish are good swimmers, but the largetooth sawfish is especially good. It can swim backwards, it can jump more than twice its own length out of the water, and it can climb over rocks and other obstacles using its fins, even if the obstacle isn’t completely submerged. It’s possible that other species of sawfish can do the same, but scientists just haven’t observed this behavior yet. We actually don’t know that much about most species of sawfish because of how rare they’ve become.

The sawfish is a type of ray, and rays are most closely related to sharks. Like sharks, rays have an internal skeleton made of cartilage instead of bone, but they also have bony teeth. You can definitely see the similarity between sharks and sawfish in the body shape although the sawfish is flattened underneath, which allows it to lie on the ocean floor. There’s also another detail that helps you tell a sawfish from a shark: the rostrum, or snout. It’s surprisingly long and studded with teeth on both sides, which makes it look like a saw.

The teeth on the sawfish’s saw are actual teeth. They’re called rostral teeth and the rostrum itself is part of the skull, not a beak or a mouth. It’s covered in skin just like the rest of the body. The sawfish’s mouth is located underneath the body quite a bit back from the rostrum’s base, and the mouth contains a lot of ordinary teeth that aren’t very sharp.

So, you may be asking, if the sawfish has plenty of teeth in its mouth, how and why does it also have those extra teeth on both sides of its saw? It’s because the rostral teeth evolved from dermal denticles. We’ve talked about dermal denticles a few times before, but a few months ago we had a Patreon bonus episode that went into more detail. In that episode, I talked about an article about a type of catfish, so let me just quote the whole section of that episode. It’s not long and I think it’s really interesting. Heck, I’ll just drop the audio in directly from that Patreon episode:

Our next article is from October 2017 and is intriguingly titled “When teeth grow on the body.” It sounds horrific, but it’s actually a study of certain catfish that grow bony plates with tiny teeth on their bodies as defense.

Catfish don’t have scales, but some species of denticulate catfish that live in South America grow bony plates that act like armor. Many of these plates are covered in thin little teeth–actual teeth, including enamel and dentin, with pulp inside. They’re called extra-oral teeth, dermal denticles, or odontodes, and the study determined that they appeared about 120 million years ago in ancient catfish that hadn’t yet evolved the bony plates. The teeth regrow when they’re lost, and in some species, males grow larger teeth than females and use them to fight other males. Imagine biting someone without needing to open your mouth.

Anyway, dermal denticles aren’t all that rare in fish. Sharks and rays are both covered with them. They’re also called placoid scales but they’re literally teeth, they’re just not used for eating. In the case of the sawfish, the rostral teeth grow much larger than an ordinary dermal denticle, and stick out sideways like the teeth of a saw. Different species have differently shaped rostral teeth. The teeth grow throughout the sawfish’s life, but unlike the teeth in the mouth, if the sawfish loses a rostral tooth, it doesn’t grow back. If it chips the top off a rostral tooth, though, that part will grow back.

The sawfish uses its rostrum to find the fish, crustaceans, and mollusks it eats. Both the rostrum and the head are packed with electroreceptors that allow the sawfish to sense tiny electrical charges that animals emit as they move. This might mean a school of fish swimming through muddy water, or it might mean a crustacean hiding in the sand. The sawfish sometimes uses its rostrum to dig prey out of the sand, but it also uses it to slash at fish or other animals. Then the sawfish can either grab the injured or dead animal with its mouth or pin it to the sea floor with its rostrum to maneuver it into its mouth. Its mouth is relatively small and it prefers to swallow its food whole, head-first, so it can only eat fish that are smaller than its mouth.

This means the sawfish leaves humans alone, because we’re way too big to fit into its mouth. It doesn’t want anything to do with us. Unfortunately, people keep bothering the sawfish, either by catching it illegally, leaving fishing nets and other trash in the ocean that sawfish and lots of other animals get tangled in, or by destroying its habitat with destructive dredging or trawling. The largetooth sawfish used to live around southern North America, but it relied on mangrove swamps to act as a nursery for baby sawfish. So many of the mangrove swamps have been destroyed so that people can build fancy hotels and shopping centers that the largetooth sawfish hasn’t been seen around North America in over 50 years, although the smalltooth sawfish is still hanging on.

Sawfish do well in captivity but require gigantic tanks, and even when given the best of care, they almost never breed in captivity. They live a long time, though, sometimes for decades.

Luckily for the sawfish, the female can reproduce without a male if she can’t find a mate. Instead of her eggs being fertilized by the male’s sperm, sometimes a female’s eggs will just develop into her genetic clones. Conservationists are working to make sure the sawfish and its habitat are protected so the babies can grow up safe and healthy.

We can’t talk about the sawfish without mentioning the sawshark. It’s a shark, not a ray, but it looks a whole lot like a sawfish–so much so that in places where both animals live, such as around Australia, people have a hard time telling them apart.

The sawshark mostly lives in much deeper water than the sawfish and is much smaller on average, about five feet long, or 1.5 meters. It has a pair of barbels about halfway down its saw that help it find food when there’s not much light to see by. Another major difference is that its gill slits are on the sides of its neck instead of under its body. It eats fish, squid, and crustaceans.

The sawshark’s rostrum also contains electroreceptors, although we don’t know for sure that it uses its saw the same way as the sawfish does. We actually don’t know very much about the sawshark, not even how many species are alive today. A new species was described in 2013 and two new species were described in 2020. There are probably more that are completely unknown to science, and maybe completely unknown to people in general.

Finally, there’s another fish that looks like a sawfish or sawshark, the sawskate, but its entire suborder, Sclerorhynchoidei, is completely extinct. It disappears from the fossil record 66 million years ago. I feel like I need a sound effect to play every time I mention that an animal went extinct 66 million years ago, to remind listeners that that’s the date of the extinction event that killed off the non-avian dinosaurs and many other animals. Maybe something like this. What do you think?

[comet sound]

Anyway, scientists are pretty sure the sawskate wasn’t very closely related to sawfish or sawsharks, but was more closely related to modern skates. Skates look a lot like rays but belong to a different family. Modern skates don’t have much of a rostrum at all, but the sawskate had a long tapering rostrum and some species had rostral teeth. Most species of sawskate were fairly small, but at least one grew an estimated 6 feet long, or about 2 meters.

If you’ve been thinking that a rostrum with teeth on both sides sounds like the kind of sword that old-timey warriors would use, you’re actually right. Traditionally, people in parts of the world where sawfish are common would sometimes use a big dried rostrum as a weapon.

These days, of course, sawfish are protected species. That means you can’t have a sawfish rostrum sword, sorry. Let the sawfish keep its sword.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!