Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 20:43 — 22.9MB)

To donate to help victims of Hurricane Helena:

Day One Relief – direct donation link

World Central Kitchen – direct donation link

It’s the big 400th episode! Let’s have a good old-fashioned mystery episode! Thanks to Richard from NC for suggesting two of our animal mysteries today.

Further reading:

A 150-Year-Old Weird Ancient Animal Mystery, Solved

The Enigmatic Cinnamon Bird: A Mythical Tale of Spice and Splendor

First ever photograph of rare bird species New Britain Goshawk

Scientists stumbled onto toothy deep-sea “top predator,” and named it after elite sumo wrestlers

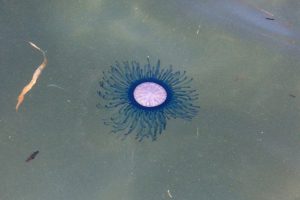

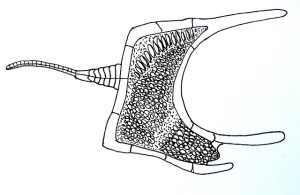

A stylophoran [drawing by Haplochromis – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10946202]:

A cinnamon flycatcher, looking adorable [photo by By https://www.flickr.com/photos/neilorlandodiazmartinez/ – https://www.flickr.com/photos/neilorlandodiazmartinez/9728856384, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=30338634]:

The rediscovered New Britain goshawk, and the first photo ever taken of it, by Tom Vieras:

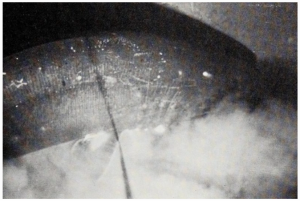

The mystery fish photo:

The yokozuna slickhead fish:

The Biotwang maker, Bryde’s whale:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

We’ve made it to the big episode 400, and also to the end of September. That means monster month is coming up fast! To celebrate our 400th episode and the start of monster month, let’s have a good old-fashioned mysteries episode.

We’ll start with an ancient animal called a stylophoran, which first appears in the fossil record around 500 million years ago. It disappears from the fossil record around 300 million years ago, so it persisted for a long time before going extinct. But until recently, no one knew what the stylophoran looked like when it was alive, and what it could possibly be related to. It was just too weird.

That’s an issue with ancient fossils, especially ones from the Cambrian period. We talked about the Cambrian explosion in episode 69, which was when tiny marine life forms began to evolve into much larger, more elaborate animals as new ecological niches became available. In the fossil record it looks like it happened practically overnight, which is why it’s called the Cambrian explosion, but it took millions of years. Many of the animals that evolved 500 million years ago look very different from all animals alive today, as organisms evolved body plans and appendages that weren’t passed down to descendants.

As for stylophorans, the first fossils were discovered about 150 years ago. They’re tiny animals, only millimeters long, and over 100 species have been identified so far. The body is flattened and shaped sort of like a rectangle, but two of the rectangle’s corners actually extend up into little points, and growing from those two points are what look like two appendages. From the other side of the rectangle, the long flat side, is another appendage that looks like a tail. The tail has plates on it and blunt spikes that stick up, while the other two appendages look like they might be flexible like starfish arms.

Naturally, the first scientists to examine a stylophoran decided the tail was a tail and the flexible appendages were arm-like structures that helped it move around and find food. But half a billion years ago, there were no animals with tails. Tails developed much later, and are mainly a trait of vertebrates.

That led to some scientists questioning whether the stylophoran was an early precursor of vertebrates, or animals with some form of spinal cord. The spikes growing from the top of the tail actually look a little bit like primitive vertebrae, made of calcite plates. That led to the calcichordate hypothesis that suggested stylophorans gave rise to vertebrates.

Then, in 2014, scientists found some exceptionally well preserved stylophoran fossils in the Sahara Desert in Africa. The fossils dated to 478 million years ago and two of them actually had soft tissue preserved as the mineral pyrite. Pyrite is also called fool’s gold because it looks like gold but isn’t, so these were shiny fossils.

When the soft tissue was observed through electron microscopes in the lab, it became clear that the tails weren’t actually tails. Instead, they were more like a starfish arm, with what may be a mouth at the base. The arm was probably the front of the animal, not the back like a tail, and the stylophoran probably used it to grab food and maybe even to crawl around.

Most scientists today agree that stylophorans are related to modern echinoderms like starfish and urchins, but there is one big difference. Echinoderms show radial symmetry, but no stylophoran found so far does. It doesn’t really even show bilateral symmetry, since the two points aren’t really symmetrical to each other. We’re also not sure what the points were for and how such an unusual body plan really worked, so there are still a lot of mysteries left regarding the stylophoran.

Next let’s talk about a mythical bird, called some variation of the word cynomolgus, or just the cinnamon bird. Naturalists from the ancient world wrote about it, including Pliny the Elder and Aristotle, and it appeared in medieval bestiaries. It was said to be from Arabia and to build its nest of cinnamon sticks in the tops of very tall trees or on the sides of cliffs.

Cinnamon comes from the inner bark of cinnamon trees, various species of which are native to southern Asia and Oceania. It’s an evergreen tree that needs a tropical or subtropical climate to thrive, and it smells and tastes really good to humans. You might have seen cinnamon sticks, which are curled-up pieces of dried cinnamon bark, and that’s the same type of cinnamon people used in the olden days. Ground cinnamon is just the powdered bark. Like many other spices, it was highly prized in the olden days and cost a fortune for just a little bit of it. Ancient Egyptians used it as part of the embalming process for mummies, ancient Greeks left it as offerings to the sun god Apollo, ancient Romans burnt it during the funerals of nobility, and it was sought after by kings throughout the world.

One interesting thing is that if you live in the United States, the cinnamon in your kitchen cupboard is probably actually cassia, also called Chinese cinnamon because it’s native to southern China. Cassia is often mentioned alongside cinnamon in old writings, because they’re so similar, but true cinnamon comes from a tree native to Sri Lanka. It’s usually marketed as Ceylon cinnamon and is more expensive, but cassia is actually better for baking. True cinnamon has a more subtle flavor that’s especially good with savory dishes, but it loses a lot of its flavor if you bake with it.

Anyway, back in the olden days, no one outside of subtropical Asia and Oceania knew where cinnamon came from. The traders who bought it from locals to resell definitely weren’t going to tell anyone where it was from. They made up stories that highlighted just how hard cinnamon was to find and harvest, to discourage anyone from trying to find cinnamon on their own and to keep prices really high. As Pliny the Elder pointed out 2,000 years ago, the cinnamon bird was one of those stories.

The cinnamon bird was supposedly the only animal that knew where cinnamon trees grew, and it would peel pieces of the bark off with its beak, then carry them to the Arabian desert or somewhere just as remote, where it would build a nest of the bark. The birds were supposed to be enormous, sometimes so big that their open wings stretched from horizon to horizon. Their nests were equally large, but so hard to reach that no human could hope to climb up and collect the cinnamon. Instead, cinnamon hunters left dead oxen and other big animals near the area where the birds had nests. The birds would swoop down and carry the oxen back to their nests to eat, and the extra weight would cause the nests to fall. In other stories, cinnamon hunters would shoot at the nests with arrows with ropes attached. Once several arrows were lodged into a nest, the hunters would pull the ropes to dislodge the nest and cause it to fall, so they could collect the cinnamon.

Of course none of that is true. Some scholars think the cinnamon bird is probably the same mythical bird as the phoenix, but without any magical abilities. Others agree with Pliny the Elder that it was just a way for traders to raise their prices for cinnamon even more. Either way, the cinnamon bird is probably not a real animal.

There are birds with cinnamon in their name, but that’s just a reference to their coloration. Cinnamon is generally a reddish-brown in color, and in animals that color is often referred to as rufous, chestnut, or cinnamon. For example, the cinnamon flycatcher, which lives in tropical and cloud forests along the Andes Mountains in South America. It’s a tiny round bird, only about 5 inches long including its tail, or 13 cm. It’s dark brown and red-brown in color with black legs and beak, and a bright cinnamon spot on its wings. It eats insects, which you could probably guess from the name.

This is what a cinnamon flycatcher sounds like:

[tiny bird sound]

Next, we need to talk about the New Britain goshawk, which Richard from NC told me about recently. It lives in tropical forests of Papua New Guinea, and is increasingly threatened by habitat loss. In fact, it’s so rare that it was only known from four specimens, and it hadn’t been officially spotted since 1969 and never photographed—until March of 2024.

During a World Wide Fund for Nature expedition, a wildlife photographer named Tom Vierus took lots of pictures of birds. One bird he photographed was a hawk sitting in a tree. He didn’t realize it was a bird that hadn’t been seen by scientists in 55 years, until later when he and his team were going through his photographs.

The goshawk is large, and is gray and white with an orange face and legs. We know very little about the bird, naturally, but now that scientists know it’s alive and well, they can work with the local people to help keep it safe. It’s called the keango or kulingapa in the local languages.

Next, we have a bona fide mystery animal, and a deep-sea mystery animal at that—the best combination!

In 1965, the U.S. Navy teamed up with Westinghouse to build a submersible designed by the famous diver and naturalist Jacques Cousteau. The craft was called Deepstar 4000 and between 1965 and 1972 when it was retired, it conducted hundreds of dives in different parts of the world, allowing scientists to learn a lot about the ocean. It could safely dive to 4000 feet, or 1200 meters, which isn’t nearly as deep as many modern submersibles, but which is still impressive.

This was long before remotely operated vehicles, so the submersible had to have a crew inside, both scientists and pilots. One of the pilots of Deepstar 4000 was a man named Joe Thompson. In 1966 Thompson maneuvered the craft to the ocean floor off the coast of California to deploy water sensors, in an area called the San Diego Trough. They touched down on the ocean floor and Thompson looked out of the tiny porthole, only to see something looking in at him.

Thompson reported seeing a fish with mottled gray-black skin and an eye the size of a dinner plate. He estimated it was 25 feet long, or over 7 ½ meters, which was longer than the Deepstar 4000 itself. Within seconds, the fish swam away into the darkness.

But that’s not the end of the story, because the water sensors the craft had already placed sensed the animal’s movement. There was definitely something really big near the craft. Even more interesting, an oceanographer had placed some underwater cameras in the area, and soon after Thompson’s sighting, the cameras took pictures of a huge gray fish.

While Thompson was positive the fish had scales, which he described as being as big around as coffee cups, the photo shows a more shark-like skin criss-crossed with scars. The oceanographer consulted with an ichthyologist, who identified the fish as a Pacific sleeper shark. We’ve talked about other sleeper sharks in episode 74. We don’t know a lot about these sharks, but they are gray, live in deep water, and can grow over 23 feet long, or 7 meters.

But Thompson was never satisfied with the identification of his mystery fish as a big Pacific sleeper shark. He was adamant that his fish had scales, a much larger eye than sharks have, and a tail that was more reminiscent of a coelacanth’s lobed tail than a shark’s tail.

One suggestion is that Thompson saw a new species of slickhead fish. Slickheads are deep-sea fish that can grow quite large, but we don’t know much about them since they live in such deep waters. The largest known species grows at least 8 feet long, or 2.5 meters, and possibly much longer. That’s the yokozuna slickhead, which was only discovered in 2021 by a scientific team studying cusk eels off the coast of Japan.

Most slickheads are small and eat plankton. This one was purplish in color, had lots of small sharp teeth, and was a strong, fast swimmer. When it was examined later, its stomach contents consisted of other fish, so it’s definitely a predator. Its eyes are also proportionately larger than a shark’s eyes. The slickhead gets its name because it doesn’t have scales on its head, but it does have scales on the rest of its body.

The yokozuna slickhead was discovered in a bay that’s well-known to both scientists and fishers, so the team didn’t believe at first that they could possibly have found a new species of fish there, especially one that was so big. But it definitely turned out to be new to science. More individuals have since been spotted, but they live very deep in the ocean, which explains why no one had seen one before. Interestingly, when the scientists first pulled the slickhead out of the water, they thought it looked a little like a coelacanth.

This episode was going to end there, but Richard from NC sent me another article about a whale mystery I’ve been talking about for years! It’s the so-called biotwang that we covered way back in episode 27.

In 2016 and early 2017, NOAA, the U.S. Coast Guard, and Oregon State University dropped a titanium-encased ceramic hydrophone into Challenger Deep. To their surprise, it was noisy as heck down there in the deepest water on earth. The hydrophone picked up the sounds of earthquakes, a typhoon passing over, ships, and whalesong—including the call of a whale researchers couldn’t identify. This is what it sounds like:

[biotwang whale call]

Well, as of September 2024, we now know what animal produces the biotwang call. It’s a whale, and one already known to science, although we don’t know much about it. It’s Bryde’s whale, a baleen whale that can grow up to 55 feet long, or almost 17 meters. The calls have all been associated with groups of Bryde’s whales, or a mother with a calf, so the scientists think the whales might use the unusual call to communicate location with its podmates. Bryde’s whales make lots of other sounds, and the scientists also think they might be responsible for some other mystery whale calls.

If you remember episode 193, about William Beebe’s mystery fish, he reported spotting a massive dark fish from his bathysphere a few decades before the Deepstar 4000 was built. He didn’t see it well enough to identify it and never saw it again. It just goes to show that there are definitely mystery animals just waiting to be discovered, whether it’s in the deep sea or perched in a treetop.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!