Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 9:35 — 10.6MB)

Thanks to Holly for suggesting this week’s topic!

Further reading:

Mermaids: Myth, Kith and Kin [this article is not for children]

A manatee:

A female grey seal, looking winsome:

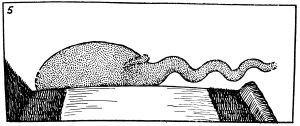

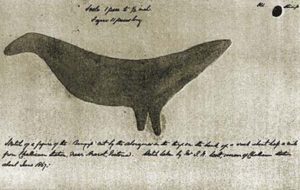

A drawing of the “original” Fiji (or Feejee) mermaid:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

Let’s close out the year 2025 with a mystery episode! Holly suggested we talk about mermaids!

Mermaids are creatures of folklore who are supposed to look like humans, but instead of legs they have fish tails. These days mermaids are usually depicted with a single tail, but it was common in older artwork for a mermaid to be shown with two tails, which replaced both legs. Not all mermaids were girls, either. Mermen were just as common.

Cultures from around the world have stories about mermaid-like individuals. Sometimes they’re gods or goddesses, like the Syrian story of a goddess so beautiful that when she transformed into a fish, only her legs changed, because her upper half was too beautiful to alter, or the Greek god Triton, who is usually depicted as a man with two fish tails for legs. Sometimes they’re monsters who cause storms, curse ships, or lure sailors to their doom. Sometimes they can transform into humans, like the story from Madagascar about a fisherman who catches a mermaid in his net. She transforms into a human woman and they get married, but when he breaks a promise to her, she turns back into a mermaid and swims away.

In 2012, a TV special aired on Animal Planet that claimed that mermaids were real, and a lot of people believed it. It imitated the kind of real documentaries that Animal Planet often ran, and the only disclaimer was in the credits. I remember how upset a lot of people were about it, especially teachers and scientists. So just to be clear, mermaids aren’t real.

Many researchers think at least some mermaid stories might be based on real animals. The explorer Christopher Columbus reported seeing three mermaids in 1493, but said they weren’t as beautiful as he’d heard. Most researchers think he actually saw manatees. A few centuries later, a mermaid was captured and killed off the coast of Brazil by European scientists, and the careful drawings we still have of the mermaid’s hand bones correspond exactly to the bones of a manatee’s flipper.

Female manatees are larger than males on average, and a really big female can grow over 15 feet long, or 4.6 meters. Most manatees are between 9 and 10 feet long, or a little less than 3 meters. Its body is elongated like a whale’s, but unlike a whale it’s slow, usually only swimming about as fast as a human can swim. Its skin is gray or brown although often it has algae growing on it that helps camouflage it. The end of the manatee’s tail looks like a rounded paddle, and it has front flippers but no rear limbs. Its face is rounded with a prehensile upper lip covered with bristly whiskers, which it uses to find and gather water plants.

The manatee doesn’t look a lot like a person, but it looks more like a person than most water animals. It has a neck and can turn its head like a person, its flippers are fairly long and resemble arms, and females have a pair of teats that are near their armpits, if a manatee had armpits, which it does not. But that’s close enough for Christopher Columbus to decide he was seeing a mermaid.

Seals may have also contributed to mermaid stories. In Scottish folklore, the selkie is a seal that can transform into human shape, usually by taking off its skin. There are lots of stories of people who steal the selkie’s skin and hide it so that the selkie will marry the person—because selkies are beautiful in their human form. Eventually the selkie finds the hidden skin and returns to the sea.

Similar seal-folk legends are found in other parts of northern Europe, including Sweden, Iceland, Norway, and Ireland. Many of the stories overlap with mermaid stories. Seals do have appealing human-like faces, have clawed front flippers that sort of resemble arms, and have rear flippers that are fused to act like a tail, even if it doesn’t look much like a fish tail.

The grey seal is a common animal off the coast of northern Europe, and a big male can grow almost 11 feet long, or 3.3 meters, although 9 feet is more common, or 2.7 meters. It has a large snout and no external ear flaps. Males are dark grey or brown, females are more silvery in color. It mainly eats fish, but will also eat other animals, including crustaceans, octopuses, other seals, and even porpoises.

While I don’t think it has anything to do with the mermaid or selkie legends, it is interesting to note that seals are good at imitating human voices. We learned about this in episode 225, about talking mammals. For instance, Hoover the talking seal, a harbor seal from Maine who was raised by a human after his mother died. Imagine if you were walking along the shore and a seal said this to you:

[Hoover the talking seal saying “Hey get over here!”]

Let’s finish with the Japanese legend of the ningyo and a weird taxidermy creature called the Feejee mermaid. The ningyo is a being of folklore that dates back to at least the 7th century. It was a fish with a head like a person, usually found in the ocean but sometimes in freshwater. If someone found a ningyo washed up on shore, it was supposed to be a bad omen, foretelling war and other disasters.

If you remember the big fish episode a few weeks ago, if an oarfish is found near the surface of the ocean around Japan, it’s supposed to foretell an earthquake. The oarfish has a red fin that runs from its head down its spine, like a mane or a comb, and the ningyo was also supposed to have a red comb on its head, like a rooster’s comb, or sometimes red hair. Some people think the ningyo is based on the oarfish. The oarfish is a deep-sea fish so it’s rare, usually only seen near the surface when it’s dying, and it has a flat face that looks more like a human face than most fish, if you squint and really want to believe you’re seeing a mythical creature.

These days, artwork of the ningyo usually looks a lot more like mermaids of European legend, but the earliest paintings don’t usually have arms, just a human head on a fish body. But by the late 18th century, a weird type of artwork had become popular among Japanese fishermen, a type of crude but inventive taxidermy that created what looked like small, creepy mermaids.

They looked like dried-out monkeys from the waist up, with a dried-out fish tail instead of legs. That’s because that’s exactly what they were. Japanese fishermen made these mermaids along with lots of other monsters, and sold them to travelers for high prices. The fishermen told tall tales about how they’d found the monster, killed it, and preserved it, and pretended to be reluctant to sell it, and of course that meant the traveler would offer even more money for it.

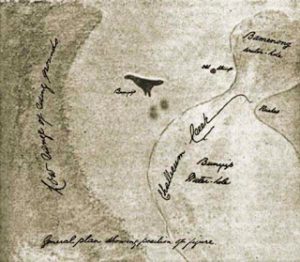

The most famous of these fake monsters was called the Fiji Mermaid, and it got famous because P.T. Barnum displayed it in his museum in 1842 and said it had been caught near the Fiji Islands, in the South Pacific. It was about three feet along, or 91 cm, and was probably made from a young monkey and a salmon.

The original Fiji mermaid was probably destroyed in a fire at some point, but it was such a popular exhibit that other wannabe showmen either bought or made replicas, some of which are still around today. People still sometimes make similar monsters, but they use craft materials instead of dead animals. They’re still creepy-looking, though, which is part of the fun.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, corrections, or suggestions, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com.

Thanks for listening!