Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 11:17 — 12.5MB)

Thanks to Charlotte, Clay, and Richard from NC for their suggestions this week!

Further reading:

Seal whiskers, the secret weapon for hunting

Elephant seals drift off to sleep while diving far below the ocean surface

Scientists Discover Remains of Antarctic Elephant Seal in Indiana River

The elephant seal and its proboscis:

The bunyip carving:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we have an animal suggested by three different listeners, Charlotte, Clay, and Richard from NC. So, by popular demand, let’s learn about the elephant seal, including some elephant seal mysteries.

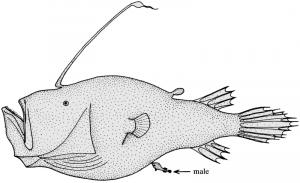

The elephant seal gets its name because it’s big, grayish-brown, and wrinkled. Adult male elephant seals even have a proboscis, although it’s not anywhere near as long as an elephant’s trunk. It’s basically an enlarged and elongated nose that allows the animal to make loud roaring noises to intimidate other males. This is what that sounds like:

[elephant seal roars]

There are two species of elephant seal, the northern and southern. The southern elephant seal is larger on average while the northern male has a larger proboscis on average. We talked about elephant seals briefly in episode 155, about sexual dimorphism, because males and females are much different in size. A big male southern elephant seal can grow up to 20 feet long, or 6 meters, and can weigh about 9,000 lbs, or 4,000 kg. Females are about half that length and much lighter in weight. A big male northern elephant seal can grow up to 16 feet long, or almost 5 meters, and weigh around 5,500 lbs, or 2,500 kg, while females are much smaller.

There are many reasons why male elephant seals are bigger than females, but it’s mainly because the males spend a lot of energy fighting each other. The bigger and stronger a male is, the more likely he is to win a fight and the more likely it is that other males won’t bother to challenge him. Meanwhile, females are smaller so they need less food.

The elephant seal has thick fur that helps keep it warm, but it also has a layer of blubber like whales do. The blubber also helps make the seal streamlined so it can swim faster. Since the elephant seal spends most of its life in the water, and it does a lot of diving, it needs to be as streamlined as possible. It eats animals like fish, squid, and octopuses, but it especially likes sharks and rays.

Since a lot of the elephant seal’s favorite prey lives on or near the ocean floor, it has to dive to find it. The deepest recorded dive of an elephant seal was almost 5,700 feet, or about 1,700 meters. That’s just over a mile deep, the deepest dive made by a mammal that isn’t a whale. The elephant seal can hold its breath for well over an hour and a half. To conserve energy and maximize its time, quite often an elephant seal will actually sleep while it’s swimming downward, since a really deep dive can take a long time to descend. It might only wake up when it bumps into the sea floor, but sometimes it’s sleeping so soundly that it will just lie there at the bottom of the ocean and continue to sleep. I guess that’s why the sea floor is sometimes called the seabed.

Because the elephant seal hunts for food where there’s not much light, it often can’t rely on its vision to find its prey. Instead, it has really good hearing underwater, and it has whiskers on its upper lip that are extremely sensitive, with more nerve fibers in each whisker than in any other mammal studied. Its whiskers can sense tiny movements of water that indicate an animal moving around nearby.

Once a year, the elephant seal molts and new fur grows in, but unlike most mammals it doesn’t just lose its fur. The outer layer of its skin peels off too. It takes a lot longer for its fur to regrow because blubber doesn’t contain any blood vessels. New blood vessels have to grow around the blubber to supply the skin with extra nutrients, and during that time the seal can’t spend time in the water or it will get too cold. It stays on land during molting, cuddled up with its friends so they can all stay warmer.

It can take a month to complete the molt, and the seals don’t eat the whole time. The males also don’t eat during mating season and the females don’t eat once their pups are born, not until the pup is a month old and doesn’t need its mother constantly. Elephant seals are adapted to be able to fast for long periods, but they do lose a lot of weight and have to eat plenty of extra food afterwards to regain it.

The elephant seal is well adapted to cold. The southern elephant seal lives in the southern ocean, around Antarctica, the southern tip of Patagonia, and south of New Zealand. The northern elephant seal lives in the eastern Pacific Ocean, off the coast of Canada and Alaska. Sometimes they roam farther, though, into warmer waters, and sometimes an elephant seal will investigate a river mouth and end up traveling far inland in the river. But sometimes a seal will make a really, really long journey.

About 1,260 years ago, one particular southern elephant seal started swimming north. It swam from the Southern Ocean along the South American coast, crossed the equator, and just kept swimming. It swam into the Gulf of Mexico and eventually came to the mouth of the Mississippi River. It swam up the mighty Mississippi and into a tributary river, and eventually it ended up in what is now Indiana, where it died.

We know all this because in 1965, construction workers found a jawbone near the Wabash River and donated it to the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. It wasn’t properly studied until decades later except to test its age. In 2020, a team of three scientists examined what was left of the jawbone after destructive radiometric testing in the 1970s, and they were shocked to realize it came from a southern elephant seal.

There are a lot of questions associated with the discovery. Why did the seal keep swimming? Was it lost and confused, and thought it was swimming back to its home? Was it just a ramblin’ seal, tryin’ to make a livin’ and doin’ the best it could feel? There’s no way to know, but there is a clue about what happened to it at the end. There are marks on the jawbone that might be cut marks.

At the time, over 1,500 years ago, that part of North America was inhabited by the Mississippian culture, a vast empire and the ancestor of many of the modern indigenous North American peoples. This was the culture who made giant earth mounds that still exist today in parts of North America, and when they were still being used, the mounds had grand buildings on top. Scientists aren’t sure if fishers or hunters spotted the elephant seal and killed it, or if someone found it already dead and decided to not let perfectly good meat go to waste. There’s even a theory that the animal didn’t swim to North America but that its skull was brought there by traders and at some point it ended up in the river.

The two elephant seal species do look very similar, and the scientists didn’t have the full original jawbone to study, so they also suggest it might actually have been a northern elephant seal. For a northern elephant seal to travel to Indiana without human help would be just as hard or even harder than a southern elephant seal, because there is no easy water passage from the Pacific coast of North America to Indiana. The seal would actually have to travel through the Arctic Ocean to the North Atlantic, then swim south to the Gulf of Mexico or the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

There is a big possibility that at least some stories of river monsters from the olden days were actually elephant seals that swam so far upstream in a river that the people who saw it didn’t know what the animal was. Even today, when many of us carry around tiny computers in our pockets that allow us to access all of humanity’s knowledge and also make phone calls, seeing an elephant seal in a place where it doesn’t belong would be terrifying.

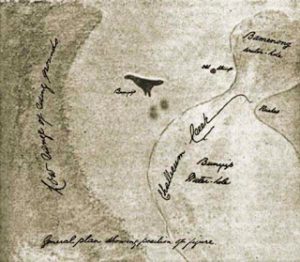

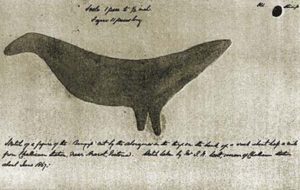

We think that’s what happened long ago in Victoria in Australia. We talked about it in episode 351, in our episode about the bunyip. An Aboriginal sacred site near Ararat, Victoria once had the outline of a bunyip carved into the ground and the turf removed from within the figure. Every year the local indigenous people would gather to re-carve the figure so it wouldn’t become overgrown, because it symbolized an important event. At that spot, two brothers had been attacked by a bunyip. It killed one of the men and the other speared the bunyip and killed it. When he brought his family and others back to retrieve his brother’s body, they traced around the bunyip’s body.

The bunyip carving was 26 feet long, or 8 meters. Unfortunately it’s long gone, since eventually the last Aborigine who was part of the ritual died sometime in the 1850s and the site was fenced off for cattle grazing. But we have a drawing of the geoglyph from 1867. It’s generally taken to be a two-legged sea serpent type monster with a small head and a relatively short, thick tail. Some people think it represents a bird like an emu.

But if you turn it around, with the small head being the end of a tail, and the blunt tail being a head, suddenly it makes sense. It’s the shape of a seal.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!