Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 13:47 — 14.1MB)

Thanks to Emma for this week’s suggestion about the magpie! We’ll learn all about the magpie and also about the mirror test for intelligence and self-awareness.

The black-billed magpie of North America (left) is almost identical in appearance to the Eurasian magpie (right):

Not all magpies are black and white. This green magpie is embarrassed by its goth cousins:

The beautiful and altruistic azure-winged magpie:

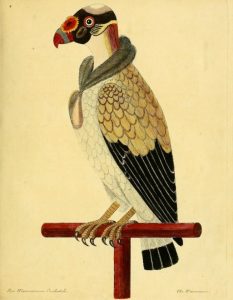

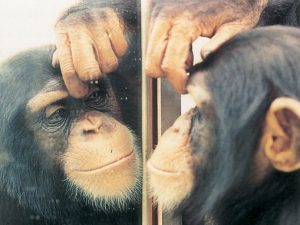

Chimps pass the mirror test. So do magpies:

The Australian magpie, or as Emma calls it, MURDERBIRD:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week let’s learn about the magpie, a frighteningly intelligent bird. Thanks to Emma for the suggestion!

The magpie is a member of the corvid family, so it’s related to crows, ravens, jackdaws, jays, rooks, and a few other kinds of birds. Most magpies are native to Europe and Asia, but there are a couple of species found in western North America. There are also two species found in Australia, but we’ll come back to those later on. People think of magpies as black and white, but some Asian species are green or blue. They look like parrots at first glance.

The most well-known magpie is the Eurasian or common magpie. Its body and shoulders are bright white and its head, tail, wings, beak, and legs are a glossy black. It has a very long tail for its size, a little longer than its body, and its wingspan is about two feet across, or 62 cm. It looks so much like the black-billed magpie of western North America that for a long time people thought the two birds were the same species.

Like most corvid species, the magpie is omnivorous. It will eat plant material like acorns and seeds, insects and other invertebrates, the eggs and babies of other birds, and roadkill and other carrion. It will also hunt small animals in groups. It mates for life and is intensely social.

The big thing about the magpie is how intelligent it is. It’s a social bird with a complex society, tool use, excellent memory, and evidence of emotions usually only attributed to mammals, like grief. An experiment with a group of Azure-winged magpies, a species that lives in Asia, shows something called prosocial behavior, which is incredibly rare except in humans and some other primates. Prosocial behavior is also called altruism. In the experiment, a magpie could operate a seesaw to deliver food to other members of its flock, but it wouldn’t get any food itself. All the magpies tested in this way made sure their bird buddies got the food. When access to the food was blocked for the other birds, the bird operating the seesaw didn’t operate it.

The magpie also passes what’s called the mirror test. The mirror test is when a researcher temporary places a colored dot on an animal’s body in a place where it can’t see it, usually the face. Then a mirror is introduced into the animal’s enclosure. If an animal sees the dot in the reflection and investigates its own body to try to examine or remove the dot, the researcher concludes that the animal understands that the reflection is itself, not another animal.

This sounds simple because most humans pass the mirror test when we’re still just toddlers. But most animals don’t. Obviously researchers haven’t been able to try the test with every single animal in the world, but even so, the results they’ve found have been surprising. Great apes pass the test, bottlenose dolphins and orcas have passed, and the European magpie has passed the test. Cleaner wrasse fish also passed the test.

You know what else passed the mirror test? Ants.

The mirror test is supposed to be a test of self-awareness, but that’s not necessarily what it’s showing. Dogs fail the mirror test but pass other tests that more clearly indicate self-awareness. But in dogs, the sense of smell is much more important than sight. Humans don’t even usually think of smell since we’re more attuned to sight and hearing, so we’ve constructed a flawed test without realizing it.

Gorillas also don’t always pass the mirror test, but researchers think this may be because in gorilla society, it’s an act of aggression to look into another gorilla’s eyes. So the gorilla looking in the mirror may literally not see the dot that was painted on its forehead while it was asleep, since it automatically avoids looking at another gorilla’s face, even its own reflection. As far as I can find, no one has tried painting the dot on bottom of the gorilla’s foot or something instead of its face.

Parrots, monkeys, lesser apes, and octopuses don’t pass the test, but all these animals express intelligence in many other ways. Not only that, but some animals that don’t technically pass the test because they don’t give any attention to the dot painted on them will use the mirror for other purposes, like looking at parts of the body they can’t ordinarily see. Asian elephants do poorly on the mirror test, but do well in other tests that measure self-awareness.

Also, most of the animals given the mirror test have never looked in a mirror before. Maybe they don’t realize that dot wasn’t always on their cheek. Or maybe they just don’t care if they’ve got a dot on their face.

That brings us to a final criticism of the mirror test. Some animals live in environments where they’re likely to see reflections. An animal that frequently sees its own reflection in still water when it drinks is more likely to understand that this is a reflection of itself. An animal that has never seen its own reflection won’t necessarily understand what it is. Even humans have this trouble. People who have been blind since birth but who regain vision later in life often don’t know what a reflection is at first. This doesn’t mean they’re stupid or not self-aware, it’s just something new that they have to learn.

But it’s still interesting that magpies pass the mirror test. Okay, let’s move on.

There are a lot of folklore traditions and superstitions about magpies. In Britain, seeing a single magpie is sometimes said to be bad luck, a sign of bad weather to come, or even an omen of death. Seeing two magpies is good luck or a good omen. In parts of Asia all magpies are considered lucky. The nursery rhyme “one for sorrow, two for joy” is originally about magpies, although as a kid I learned it about crows since I live in a part of the world where we don’t have magpies. The rhyme varies, but the version I learned is “one for sorrow, two for joy, three for a girl, four for a boy, five for silver, six for gold, and seven’s a secret that’s never been told.”

Magpies are supposed to be attracted to shiny objects and are thought of as thieves. There’s a whole opera about this, Rossini’s La Gazza Ladra, about a girl who’s accused of stealing a silver spoon. The girl is convicted and condemned to death, but just in time the spoon is discovered in a magpie’s nest and the girl is pardoned. You’ve probably heard the overture to this opera without knowing it, since it appears in a lot of movies.

But do magpies really steal shiny things like jewelry, coins, and silver spoons? Results of a study of wild common magpies indicate that they don’t. A few of the magpies investigated the shiny objects, but none took any and most birds were wary of getting too close to items they’d never seen before.

Many people think magpies are pests who chase off or kill other songbirds, steal things, and are basically taking over the world. That’s actually not the case. The magpie is an important part of its ecosystem, and areas with plenty of magpies actually have healthier populations of other songbirds. The black-billed magpie of North America will hang around herds of cattle, cleaning the animals of ticks and other insects.

Let’s return now to the Australian magpies I mentioned earlier. The black magpie is mostly black with white on its wings. It’s actually not closely related to the magpie at all but is a species of treepie. Other treepies are found in southeast Asia. Treepies are corvids, but they’re not closely related to magpies although they look similar.

The Australian magpie also looks similar to the common magpie, but it’s not a corvid, although its family is distantly related to the corvid family. It’s mostly black with white markings and a heavy silvery-white bill with a black tip. It lives in Australia, southern New Guinea, and has been introduced to New Zealand, where it’s an invasive pest that displaces native birds. It’s about the size of the common magpie, but more heavily built with a shorter tail. It mostly eats insects and other invertebrates, but it is omnivorous. Researchers have noticed that some Australian magpies dunk insects in water before eating them, a practice seen in many species of birds. It doesn’t just dip the insect in the water, though, it thrashes it around. Researchers theorize that this helps rid certain insects of toxins and therefore improves the taste.

If someone gets too close to an Australian magpie’s nest, it will divebomb them, especially the male. It may also peck at the face, sometimes causing injuries. Sometimes people will paint eyes on the back of a hat to try and fool a magpie into attacking the painted face instead of their actual face, although this generally doesn’t work. The magpie especially attacks people who are moving fast, like joggers and bicyclists, so some bike helmets have spikes on them to stop magpies from diving at them. But since a magpie will also sometimes land on the ground in front of a person, then fly up and attack their face from that angle, it doesn’t really matter what kind of hat you wear. It’s probably safest to avoid magpies who are nesting. The babies will be grown and flown away soon enough and then you can have your public park back.

Australian magpies also chase off predatory birds, mobbing them the same way crows and other birds mob hawks.

The Australian magpie is also an intelligent bird. Researchers think intelligence in birds and animals of all kinds is linked to sociability, and Australian magpies are just as social as their far-distant Eurasian and North American cousins. Magpies who grow up in larger groups score higher on tests of intelligence than magpies from smaller groups. The larger a group, the more complex the social interactions required of an individual bird, which drives cognitive development.

The Australian magpie has an amazing singing voice and can mimic other birds and animals. It even sometimes imitates human speech. A magpie may sing constantly for over an hour at a time, and pairs often call together. These duets actually indicate to other birds that the pair is working together to defend their territory, so maybe if you hear it it’s time to put on the bike helmet with spikes.

This is what an Australian magpie sounds like:

[magpie call]

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!