Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 12:12 — 13.6MB)

Thanks to Riley and Dean, Elizabeth, and Leo for their suggestions this week!

Further reading:

Groundbreaking study reveals extensive leatherback turtle activity along U.S. coastline

A bearded dragon:

The tiny bog turtle:

The massive leatherback sea turtle:

The beautiful hawksbill turtle [photo by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service]:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to learn about some reptiles suggested by four different listeners: Riley and Dean, Elizabeth, and Leo.

We’ll start with the brothers Riley and Dean. Dean wants to learn more about the bearded dragon, and that may have something to do with a certain pet bearded dragon named Kippley.

“Bearded dragon” is the name given to any of eight species of lizard in the genus Pogona, also referred to as beardies. They’re native to Australia and eat plants and small animals like worms and insects. They can grow about two feet long, or 60 cm, including the tail, but some species are half that length. Females are a little smaller than males on average.

The bearded dragon gets its name because its throat is covered with pointy scales that most of the time aren’t very noticeable, but if the lizard is upset or just wants to impress another bearded dragon, it will suck air into its lungs so that its skin tightens and the spiky scales under its throat and on the rest of its body stick out. They’re not very sharp but they look impressive. Since the bearded dragon can also change color to some degree the same way a chameleon can, when it inflates its throat to show off its beard, the beard will often darken in color to be more noticeable. Both males and females have this pointy “beard.”

Bearded dragons that are sold as pets these days are more varied and brighter in color than their wild counterparts, although wild beardies can be brown, reddish-brown, yellow, orange, and even white. Australia made it illegal to catch and sell bearded dragons as pets in the late 20th century, but there were already lots of them outside of Australia by then. Pet bearded dragons are mainly descended from lizards exported during the 1970s, which means they’re quite domesticated these days and make good pets.

Like some other reptiles and amphibians, the bearded dragon has a third eye in the middle of its forehead. If you have a pet beardie and are about to say, “no way, there is definitely not a third eye anywhere, I would have noticed,” the eye doesn’t look like an eye. It’s tiny and is basically just a photoreceptor that can sense light and dark. Technically it’s called a parietal eye and researchers think it helps with thermoregulation.

Next, Riley wants to learn about turtles, AKA turbles, and especially wants everyone to know the difference between a tortoise and a turtle. It turns out that while many turtles are just fine living on land, they’re often more adapted to life in the water. Turtles have a more streamlined shell and often flipper-like legs or webbed toes. Tortoises only live on land and as a result they have shells that are more dome-shaped, and they have large, strong legs that resemble those of a tiny elephant.

You can’t always go by an animal’s common name to determine if it’s a tortoise or a turtle, but it’s also not always clear whether an animal is a tortoise or a turtle at first glance. Take the eastern box turtle, for instance, which is common in the eastern United States. It has a domed carapace, or shell, but it’s still a turtle, not a tortoise. And, I’m happy to say, it can swim quite well. This is a relief to find out because when I was about six years old, my mom visited someone who had kids a little older than me. I didn’t know them but they were nice and showed me the swampy area near their house. At one point one of the older boys found a box turtle, took it over to a little bridge over a pond, and dropped it in the water. I screamed, and he was absolutely shocked. He said he thought box turtles belonged in the water and he was helping it, but I thought they couldn’t swim and he’d just killed the poor turtle. I have continued to think he’d killed the poor turtle until just now, when I learned they can swim, and I can’t even tell you how relieved I am. Anyway, eastern box turtles have a domed shell, yes, and stumpy club-like front legs, but their hind legs are less like elephant legs than regular turtle legs. Since box turtles can live to be 100 years old, it’s possible that that one is alive and well even now.

Riley also wants everyone to know not to take a turtle from the woods, which is a very good rule to live by. In fact, it’s important not to take any wild animals from the woods no matter how cute they are. To continue our example, eastern box turtles have small territories that they defend from other box turtles. If you take the turtle out of its territory even for just a few days, when you return it to the woods, another turtle may have already taken over and will chase it away. Turtles don’t travel very fast and are vulnerable to being hit by cars and eaten by lots of different predators, so without a safe territory where it can hide and find food, it can die very quickly.

One of the turtles Leo suggested we learn about was the bog turtle. It’s the smallest turtle in North America, with a carapace barely four inches long, or 10 cm. It lives in a few parts of the eastern United States, and likes marshy areas with slightly acidic water. It spends a lot of time in the water, but also plenty of time on land. It eats worms, slugs, snails, water plants, berries, insects, and even small frogs when it can catch them.

The bog turtle is so small that pretty much anything big enough to swallow it will eat it. Its main defense is to bury itself in soft mud and hide. It’s almost completely black or dark gray in color, but it does have a bright orange spot on each side of its neck.

The bog turtle is critically endangered due to habitat loss, pollution, and poaching for the illegal pet trade. Conservationists are working to improve its habitat, and in the meantime some zoos and aquariums are helping with a captive breeding program. Since a bog turtle isn’t old enough to lay eggs until it’s at least 8 years old, the species as a whole reproduces slowly.

Leo also suggested hawksbill and leatherback turtles, and Elizabeth wants to learn about sea turtles in general. We talked about sea turtles way back in episode 75, so it’s definitely time to revisit the topic.

Seven species of sea turtle are alive today, and you can tell they’re turtles and not tortoises because they have streamlined shells and flippers instead of feet. They migrate long distances to lay eggs, thousands of miles for some species and populations, and usually return to the same beach where they were hatched. Female sea turtles come ashore to lay their eggs in sand, but the males of most species never come ashore. The exception is the green sea turtle, which sometimes comes ashore just to bask in the sun. Once the babies hatch, they head to the sea and take off, swimming far past the continental shelf where there are fewer predators. They live around rafts of floating seaweed call sargassum, which protects them and attracts the tiny prey they eat.

Six of the extant sea turtles are relatively small. Not small compared to regular turtles, small compared to the seventh living sea turtle, the leatherback. It’s much bigger than the others and not very closely related to them. It can grow some nine feet long, or 3 meters, and instead of having a hard shell like other sea turtles, its carapace is covered with tough, leathery skin studded with tiny osteoderms. Seven raised ridges on the carapace run from head to tail and make the turtle more stable in the water, a good thing because leatherbacks migrate thousands of miles every year. Not only is the leatherback the biggest and heaviest turtle alive today by far, it’s the heaviest living reptile that isn’t a crocodile. It has huge front flippers, is much more streamlined even than other sea turtles, and has a number of adaptations to life in the open ocean.

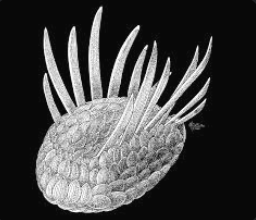

The leatherback lives throughout the world, from warm tropical oceans up into the Arctic Circle. It mostly eats jellyfish, so it goes where the jellyfish go, which is everywhere. It also eats other soft-bodied animals like squid. To help it swallow slippery, soft food when it doesn’t have the crushing plates that other sea turtles have, the leatherback’s throat is full of backwards-pointing spines. What goes down will not come back up, which is great when the turtle swallows a jellyfish, not so great when it swallows a plastic bag. It’s endangered due to pollution, accidental drowning when it gets caught in fishing nets, and habitat loss of its nesting beaches.

The hawksbill, or hawkbill sea turtle grows to a much more reasonable size, around three feet long, or 90 cm, and mostly lives around tropical reefs. It has a more pointed, hooked beak than other sea turtles, sort of like a hawk, which gives it its name. You might think it eats fish with a beak like that, but it mostly eats jellyfish and sea sponges. It especially likes the sea sponges, some of which are lethally toxic to most other animals. It also doesn’t have a problem eating even extremely stingy jellies and jelly-like animals like the Portuguese man-o-war. The hawkbill’s head is armored so the stings don’t bother it, although it does close its eyes while it chomps down on jellies. Its meat can be toxic due to the toxins it ingests. People used to kill hawksbill sea turtles for their multicolored shells, but these days it’s a protected species like all sea turtles.

The hawksbill is also biofluorescent! Researchers only found this out by accident in 2015, when a team studying biofluorescent animals in the Solomon Islands saw and filmed a hawksbill glowing like a UFO with neon green and red light. So you never know what other secrets sea turtles might be hiding.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!