Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 16:51 — 12.7MB)

This week is Connor’s episode, and we’re going to learn about some animals that don’t conform to “typical” gender roles, one way or another.

I’ll be at ConCarolinas this week, from June 3 through 5, including recording a live crossover episode with Arcane Carolinas!

Further reading:

Species of algae with three sexes that all mate in pairs identified in Japanese river

How a microbe chooses among seven sexes

Facultative Parthenogenesis in California Condors

Chinstrap penguins make good dads:

Laysan albatrosses make good moms:

Black swans make good dads:

Some rams really like other rams (photo by Henry Holdsworth):

New Mexico whiptail lizards are all females:

California condor females don’t always need a male to produce fertilized eggs:

Clownfish change sex under some circumstances:

The white-throated sparrow essentially has four sexes:

You are awesome (photo by By Eric Rolph)!

Show transcript:

“Hey y’all, this is Connor. Welcome to a very special Pride Month edition of the Strange Animals Podcast.”

This week we have Connor’s episode! We decided to make it the very last episode in our Kickstarter month so that it’s as close to the month of June as possible, because June is Pride Month and our episode is about gender-diverse animals! Don’t worry, parents of very young children, we won’t be discussing mating practices except in very general terms.

Pride month celebrates people’s differences when it comes to gender expression and sexuality. That’s why its symbol is the rainbow, because a rainbow is made up of all different colors the same way there are different kinds of people. Sometimes people get angry when they hear about Pride month because they think there are only two genders, and that those two genders should only behave in certain ways. Pffft. That’s not even true when it comes to animals, and humans are a lot more socially complicated.

For instance, let’s start by talking about a humble creature called algae. If you remember episode 129, about the blurry line between animals and plants, you may remember that algae isn’t actually a plant or an animal. Some species resemble plants more than animals, like kelp, but they’re not actually plants. In July of 2021, scientists in Japan announced that a species of freshwater algae has three sexes: male, female, and bisexual. All three sexes can pair up with any of the others to reproduce and their offspring may be male, female, or bisexual at random.

Even though the algae has been known to science for a long time, no one realized it has three sexes because most of the time, algae reproduces by cloning itself. The research team thinks that a lot of algae species may have three sexes but researchers just haven’t been looking for it.

Yes, I realize that was a weird place to start, but it’s also fascinating! It’s also not even nearly as complicated as a protozoan called Tetrahymena thermophila, which has seven sexes.

Let’s look at a bird next, the penguin. You’ve probably heard of the book And Tango Makes Three, about two male penguins who adopt an egg and raise the baby chick together. For some reason some people get so angry at those penguins! Never trust someone who doesn’t like baby penguins, and never trust someone who thinks animals should act like humans. The events in the book are based on a true story, where two male chinstrap penguins in New York’s Central Park Zoo formed a pair bond and tried to hatch a rock, although they also tried to steal eggs from the other penguins. A zookeeper gave the pair an extra penguin egg to hatch instead.

The most interesting thing about the story is that same-sex couples are common among penguins, in both captivity and in the wild, among both males and females. Since penguins sometimes lay two eggs but most species can only take care of one chick properly, zookeepers often give the extra eggs to same-sex penguin pairs. The adoptive parents are happy to raise a baby together and the baby is more likely to survive and be healthy. Occasionally a same-sex penguin couple will adopt an egg abandoned by its parents.

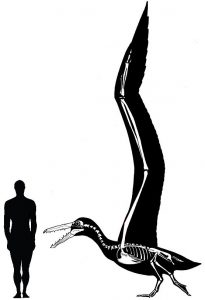

If you remember episode 263 a few months ago, where we talked about animals that mate for life, you may remember the Laysan albatross. In that episode we learned about a specific Laysan albatross named Wisdom, the oldest wild bird in the world as far as we know. While I was researching Wisdom, I learned something marvelous. As many as 30% of all Laysan albatross pairs are both females. Sometimes one of the females will mate with a male and lay a fertilized egg, and then both females raise the baby as a couple. Sometimes one of the females lays an unfertilized egg that doesn’t hatch. There are many more Laysan albatross females than males, which may be the reason why females form pairs, but it’s perfectly normal behavior. It’s also been a real help to conservationists. Sometimes an albatross pair will nest in an area that’s not safe, like on an airfield. Instead of leaving the egg to be smashed by an airplane, conservationists take the fertilized egg from the unsafe nest and use it to replace the unfertilized egg of a female pair. The egg is safe and the chick has adoptive parents who raise it as their own.

Many other birds develop same-sex pairs too. This is especially common in the black swan, where up to a quarter of pairs are both male. One or both of the males will mate with a female, but after she lays her eggs the males take care of them and the cygnets after they hatch. Cygnets raised by two dads are much more likely to survive than cygnets raised by one mom and one dad. The males are stronger and more aggressive, so they can defend the nest and babies more effectively.

Birds aren’t the only animals that form same-sex pair bonds. Many mammals do too. It’s been documented in the wild in lions, elephants, gorillas, bonobos, dolphins, and many more. In species that don’t typically form pair bonds, homosexual behavior is still pretty common. It’s so common among domestic sheep that shepherds have to take into account the fact that up to 10% of rams prefer to mate with other rams instead of with ewes. Some rams show attraction to both males and females. This happens in wild sheep too, where rams may court other rams the same way they court ewes. Some ewes also show homosexual behavior.

The New Mexico whiptail is a lizard that lives in parts of the southwestern United States and northern Mexico. It can grow over nine inches long, or 23 cm, and is black or brown with yellow racing stripes. It eats insects and is an active, slender lizard that’s common throughout its range. And every single New Mexico whiptail lizard is a female.

The lizards reproduce by a process called parthenogenesis. That basically means an animal reproduces asexually without needing to have its eggs fertilized. The lizards do mate, though, but not with males. Females practice mating behaviors with each other, which researchers think causes a hormone change that allows eggs to develop. Females who don’t mate don’t develop eggs.

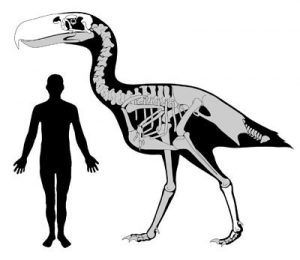

Female birds can sometimes reproduce asexually too. It’s been documented in turkeys, chickens, pigeons, finches, and even condors. A study published in late 2021 detailed two instances of parthenogenesis in California condors in a captive breeding program. In both cases the females were housed with their male mates, and in both cases the pairs had produced offspring together before. But in both cases, for some reason the females laid eggs that hatched into chicks that were genetically identical to the mothers. It’s possible parthenogenesis is even more common in birds than researchers thought.

In many species of reptile, whether a baby is a male or female depends completely on how warm its egg gets during incubation. For example, the American alligator. The mother gator builds a nest of plant material and lays her eggs in it. As the plant material decays, it releases heat that keeps the eggs warm. How much heat is generated depends on where the mother alligator builds her nest and what plants she uses, which in turns affects the eggs. If the temperature in the nest is under 86 degrees Fahrenheit, or 30 Celsius, during the first few weeks of incubation, most or all of the eggs will hatch into females. If the temperature is 93 F or 34 C, most or all of the eggs will hatch into males. If the temperature is between the two extremes, there will be a mix of males and females, although usually more females.

Because climate change has caused an overall increase in temperatures across the world, some already vulnerable reptile populations, especially sea turtles, are hatching almost all males. Conservationists have to dig up the eggs and incubate them at a cooler temperature in captivity, then release the babies into the ocean when they hatch.

Other animals change from male to female or vice versa, depending on circumstances. The clownfish, for example. Clownfish start out life as males but as they grow up, most become females, although only the dominant pair in a colony actually reproduces. Clownfish live in colonies led by the largest, most aggressive female, with the largest, most aggressive male in the group as her mate. If something happens to her, her former mate takes her place, becoming a female in the process. The largest juvenile male then becomes her mate and remains male even though he puts on a growth spurt to mature quickly. If Finding Nemo was scientifically accurate, it would have been a much different movie.

Another group of fish that live around reefs are wrasses, which includes the famous cleaner fish that cleans parasites and dead tissue off of larger fish. Wrasses hatch into both males and females, but the males aren’t the same type of males that can breed. Those develop later. When the dominant breeding male of the group dies, the largest female or the largest non-breeding male then develops into a breeding male. But sometimes a non-breeding male will develop into a female instead.

The term for an animal that changes sex as part of its natural growth process is sequential hermaphroditism. It’s common in fish and crustaceans in particular. Other animals have the reproductive organs of both a male and a female, especially many species of snail, slug, earthworm, sea slug, and some fish. We talked about the mangrove killifish in episode 133, and in that episode I said it was the only known vertebrate hermaphrodite. That’s actually not accurate, although I was close. It’s the only known vertebrate hermaphrodite that can self-fertilize. Almost all mangrove killifish are females, although they also produce sperm to fertilize their own eggs. The eggs hatch into little clones of the mother.

We’ve talked about seahorses before too, especially in episode 130. Seahorse pairs form bonds that last throughout the breeding season. The pair participate in courtship dances and spend most of their time together. When the eggs are ready, the female deposits them in a special brood pouch in the male’s belly, where he fertilizes them. They then embed themselves in the spongy wall of the brood pouch and are nourished not only by the yolk sacs in the eggs, but by the male, who secretes nutrients in the brood pouch. So basically the male is pregnant. The female visits him every day to check on him, usually in the mornings. When the eggs hatch after a few weeks, the male expels the babies from his pouch and they swim away, because when they hatch they are perfectly formed teeny-tiny miniature seahorses.

Let’s finish with a little songbird that’s common throughout eastern North America, the white-throated sparrow. It has a white patch on its throat and a bright yellow spot between the eye and the bill. There are two color morphs, one with black and white stripes on its head, one with brown and tan stripes on its head. Both males and females have these head stripes. The male sings a pretty song that sounds like this:

[white-throated sparrow call]

A 30-year study into white-throated sparrow genetics has revealed some amazing things. The color morphs are due to a genetic difference that affects a lot more than just feather colors. Black morph males are better singers, but they don’t guard their territory as well or take care of their babies as well as brown morphs do. They also aren’t as faithful to their mates as the brown morph males, which are fully monogamous and are diligent about helping take care of their babies. Despite their differences in raising offspring, both morphs are equally successful and equally common.

All this seems to be no big deal on the surface, maybe just pointing to the possibility that the species is in the process of splitting into two species or subspecies. But that’s not the case.

Black morphs always mate with brown morphs. A black morph male will always have a brown morph mate, and vice versa. Genetically, the two morphs are incredibly different—so different, in fact, that they seem to be developing a fully different set of sex chromosomes. In other words, there are male and female black morph birds and male and female brown morph birds that are totally different genetically, but still members of the same species that only ever breed with each other. In essence, the white-throated sparrow has four sexes.

Usually I try to end episodes with something funny, but today I’m going to speak directly to you. Yes, you! If you’re listening to this or reading the transcript, my words are meant just for you. You are an amazing person and I love you. You deserve to be happy. If anyone has ever told you there’s something wrong with the way you are, or the way you wish you were or want to be, they’re wrong. They probably also don’t like penguins, so you don’t have to believe anything they say. If you’ve ever read books by Terry Pratchett, you may recognize this quote: “Be yourself, as hard as you can.”

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!