Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 10:52 — 12.2MB)

Thanks to Hannah, who suggested sheep as this week’s topic! We’ll also learn about a few other hoofed animals, including the weird giraffe relative, sivatherium.

Further reading:

The American Jacob Sheep Breeders’ Association

What happened with that Sumerian ‘sivathere’ figurine after Colbert’s paper of 1936? Well, a lot.

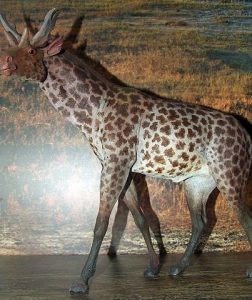

A Jacob sheep ewe with four horns (pic from JSBA site linked above):

The male four-horned antelope [photo by K. Sharma at this site]:

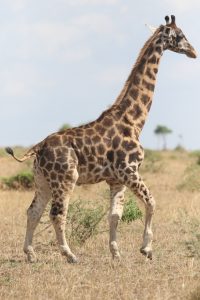

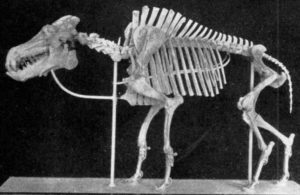

A modern reconstruction of sivatherium that looks a lot like a giraffe [By Hiuppo – Own work, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2872962]:

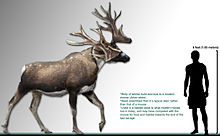

The rein ring in question (on the left) that might be a siveratherium but might just be a deer:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to look at an animal suggested by Hannah a long time ago. Hannah suggested we talk about sheep, and I can’t even tell you how many times I almost did this episode but decided to push it back just a little longer. Finally, though, we have the sheep episode we’ve all been waiting for! We’re also going to learn about a strange animal called sivatherium and a mystery surrounding when it went extinct.

The sheep has cloven hooves and is a ruminant related to goats and cattle. It mostly eats grass, and it chews its cud to further break down the plants it eats. It’s one of the oldest domesticated animals in the world, with some experts estimating that it was first domesticated over 13,000 years ago. Mammoths still roamed the earth then. Sheep are especially useful to humans because not only can you eat them, they produce wool.

Wool has incredible insulating properties, as you’ll know if you’ve ever worn a wool sweater in the snow. Even if it gets wet, you stay nice and warm. Even better, you don’t have to kill the sheep to get the wool. The sheep just gets a haircut every year to cut its wool short. Wild sheep don’t grow a lot of wool, though. They mostly have hair like goats. Humans didn’t start selecting for domestic sheep that produced wool until around 8,000 years ago.

Like other animals that were domesticated a very long time ago, including dogs and horses, we’re not sure what the direct ancestor of the domestic sheep is. It seems to be most closely related to the mouflon, which is native to parts of the middle east. The mouflon is reddish-brown with darker and lighter markings and it looks a lot like a goat. Other species of wild sheep live in various parts of the world but aren’t as closely related to the domestic sheep. The bighorn and Dall sheep of western North America are closely related to the snow sheep of eastern Asia and Siberia. The ancestors of all three species spread from eastern Asia into North America during the Pleistocene when sea levels were low and Asia and North America were connected by the land bridge Beringia.

The male sheep is called a ram and grows horns that curl in a spiral pattern, while the female sheep is called a ewe. Some ewes have small horns, some don’t. This is the case for both wild and domestic sheep. Sheep use their horns as defensive weapons, butting potential predators who get too close, and they also butt each other. Rams in particular fight each other to establish dominance, although ewes do too.

But some breeds of domestic sheep are what is called polycerate, which means multi-horned. That means a sheep may have more than two horns, typically up to six. Many years ago I kept a few Jacob sheep, which are a polycerate breed, and in a Patreon episode from 2018 I went into really too much detail about this particular breed of sheep. I will cut that short here.

The Jacob is a hardy, small sheep with tough hooves, and it’s white with black spots. Ideally, a Jacob sheep will have four or six well-balanced horns. In a six-horned sheep, the upper pair branch upward, the middle pair curl like an ordinary ram’s horns, and the lower pair branch downwards. Sometimes a sheep will have three or five horns, or will start out with four horns but as they grow, two will merge so it looks like they have a single horn on one side. Sometimes a ram’s horns will grow so large that the blood supply is choked off for the lower pair, which will die and stop growing. Breeding a pair of six-horned Jacob sheep doesn’t guarantee that the babies will have more than two horns, though. It’s still a recessive trait.

Sheep, goats, cattle, and some antelopes are all bovids. Polyceratism appears to be a bovid trait. It’s caused by a mutation where the horn core divides during the animal’s development.

Occasionally, a sheep of non-polycerate breed, or a goat, or even a cow, is born with multiple horns. The blue wildebeest is also occasionally born with multiple horns. Sometimes an animal grows a lot of horns, like eight, but usually it’s three, four, five, or six.

Another animal with more than two horns is the four-horned antelope that lives in India and Nepal. Its horns are quite small, just a pair of tiny points on the forehead with a pair of longer points behind them. The antelope itself is also small, not much more than two feet tall at the shoulder, or 60 cm. Its coat is reddish or yellowish-brown with white underparts, and a black stripe down the front of the legs. The longer horns grow up to about five inches long, or 12 cm, but the front horns are no longer than two inches, or five cm.

The four-horned antelope is shy and solitary, and lives in open forests near water. Since it’s so small, it frequently hides in tall grasses. Sometimes a four-horned antelope’s front two horns are just bumps covered with fur, which makes them look like ossicones although they’re still actually horns.

That brings us to the other group of animals with multiple horns, although they’re not actually horns. I mentioned ossicones in the tallest animals episode, about giraffes. They’re made of ossified cartilage instead of bone, and are covered in skin and fur instead of a keratin sheath. Antlers are actually very similar to ossicones in many ways. A deer’s antlers grow from a base that is similar to an ossicone, and as they grow, the antlers are covered with tissue called velvet that later dries and is scraped off by the deer to show off the bony antlers. Unlike horns, which are always unbranched, the ossicones of some extinct animals can look like antlers.

We talked about sivatherium in episode 256, about mammoths. It was an ancestor of modern giraffes that lived in Africa and India around a million years ago. It stood around 7 feet tall at the shoulder, or just over two meters, but had a relatively long neck that made it almost 10 feet tall in total, or about three meters. It had two pairs of ossicones, one pair over its eyes and another between its ears. Like the four-horned antelope, the front pair were smaller than the rear pair, but the rear pair was broad and had a single branch.

Sivatherium was once believed to be closely related to elephants, and reconstructions of it often made it look like a moose with a short trunk. But modern understanding of its anatomy suggests it looked like a heavily built giraffe with shorter legs and neck, sort of like the giraffe’s closest living relative, the okapi.

One interesting thing about Sivatherium is how recently it may have been alive. Some researchers think it may have been around only 8,000 years ago. There’s rock art in India and the Sahara that does seem to show a long-necked animal with horns that isn’t a giraffe. The art has been dated to around 15,000 years ago. But the big controversy is a figurine discovered in 1928.

That’s when a copper rein ring was found in Iraq and dated to about 2800 BCE. A rein ring was part of the harness to a four-wheeled chariot, with two holes to thread the reins through to keep them from tangling. Above the rings was a little decorative figure of an animal. This particular rein ring’s figure shows an animal with short horns above the eyes and branching horn-like structures farther back, between the ears. When it was originally discovered, scientists thought the figure represented a type of fallow deer found in the area, with the ends of the antlers broken off. But one researcher, Edwin Colbert, pointed out that no deer known has four antlers and the figure clearly has two little bumps over its eyes that are separate from the branched antler or horn-like structures farther back. In 1936 he published his conclusion that the animal wasn’t a deer at all but sivatherium, and a lot of scientists agreed.

That would mean sivatherium might have been alive less than 5,000 years ago. Part of the issue is that sivatherium’s branched ossicones weren’t very big in comparison to its head, while the fallow deer’s antlers are proportionally quite large. The figurine has structures that match sivatherium’s ossicones more than a deer’s antlers. But in 1977, two little pieces of copper were found in a storage box where they’d been since the original discovery of the rein ring. The pieces fit exactly onto the ends of the figure’s horns, showing that the horns are much bigger than originally thought.

That doesn’t explain everything, though. The figure still has those extra little horns over its eyes, and while the branched horns look like deer antlers, they still don’t look like fallow deer antlers. Some researchers point out that sivatherium had a lot of variation in the size and shape of its ossicones, too.

Ultimately there’s not enough evidence either way of whether the figurine depicts a deer or sivatherium. If sivatherium did live as recently as a few thousand years ago, hopefully remains of it will be found soon. Until we know for sure, you can still be glad that the giraffe is alive, because it’s just as amazing as its extinct relation.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!