Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 17:33 — 19.4MB)

Sign up for our mailing list! We also have t-shirts and mugs with our logo!

It’s our fourth annual updates and corrections episode! I’ve already had to make a correction to this episode!

Further reading:

Cassowary, a rare emu-like bird, attacks and kills Florida man, officials say

3D printed replicas reveal swimming capabilities of ancient cephalopods

Enormous ancient fish discovered by accident

A rare observation of a vampire bat adopting an unrelated pup

Pandemic paleo: A wayward skull, at-home fossil analyses, a first for Antarctic amphibians

Neanderthals and Homo sapiens used identical Nubian technology

Entire genome from Pestera Muierii 1 sequenced

Animal Species Named from Photos

Cryptophidion, named from photos:

The sunbeam snake showing off that iridescence:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

It’s our fourth annual updates and corrections episode, and to keep it especially interesting we’ll also learn about a mystery snake. Make sure to check the show notes for lots of links if you want to learn more about these updates.

First, we have a small correction from episode 222. G emailed with a link about a Florida man who was killed by a cassowary in 2019, so cassowaries continue to be dangerous.

We also have a correction from episode 188, about the hyena. I called hyenas canids at one point, and although they resemble canids like dogs and wolves, they’re not canids at all. In fact, they’re more closely related to cats than dogs. Thanks to Bal for the correction!

In response to the talking animals episode, Merike told about a dog who uses computer buttons to communicate. The dog is called Bunny and she’s completely adorable. I’ll link to her facebook page. I have my doubts that she’s actually communicating the way it looks like she is. She’s obviously a clever dog but I don’t think she understands the English language so well that she can choose verbs like “is” from her list of words. I think she’s probably mostly taking unconscious cues from her owner. But I would be happy to be proven wrong.

Following up from our recent deep-sea squid episode, a team of paleontologists studying ancient cephalopods 3-D printed some replicas of what the animals would have looked like while alive. Then they took the models into a swimming pool and other water sources to study how their shells affected the way they could move through the water. They discovered that a type of cephalopod with a straight shell, called an orthocone, probably mostly moved up and down in the water to find food and could have moved extremely fast in an upward or downward direction. A type of cephalopod with a spiral shaped shell, called a torticone, also spun slightly as it moved around. The same team has previously worked with 3-D models of ammonoids, which we talked about in episode 86. The models don’t just look like the living animals, they have the same center of balance and other details, worked out mathematically.

Speaking of ancient animals, a collector in London bought a fossil found in Morocco thinking it was part of a pterodactyl skull. When the collector asked a palaeontologist to identify it, it turned out to be a fossilized coelacanth lung. The collector donated the fossil for further study, and the palaeontologist, David Martill, worked with a Brazilian coelacanth expert, Paulo Brito, to examine the fossil.

The fossil dates to the Cretaceous, about 66 million years ago, and is bigger than any coelacanth lung ever found. Modern coelacanths grow a little over six feet long at most, or 2 meters, but the estimated length of this Coelacanth is some 16 ½ feet, or 5 meters. The fossil is being donated to a university in Morocco.

We talked about vampire bats way back in episode 11, and I love bats and especially vampire bats so I try to keep an eye on new findings about them. Everyone thinks vampire bats are scary and creepy, but they’re actually social, friendly animals who don’t mean to spread rabies and other diseases to the animals they bite. It just happens.

Vampire bats live in colonies and researchers have long known that if a female dies, her close relations will often take care of her surviving baby. Now we have evidence that at least sometimes, the adoptive mother isn’t necessarily related to the birth mother. It’s from a recently published article based on a study done in 2019.

A team researching how unrelated vampire bats form social bonds captured 23 common vampire bats from three different colonies and put them together in a new roost where their interactions could be recorded by surveillance cameras. One particular pair of females, nicknamed Lilith and BD, became good friends. They groomed each other frequently and shared food. If you remember from episode 11, vampire bats share food by regurgitating some of the blood they drank earlier so the other bat can lap it up. Since vampire bats can starve to death in only a few nights if they can’t find blood, having friends who will share food is important.

During the study, Lilith gave birth to a baby, but shortly afterwards she started getting sick. She had trouble getting enough food and couldn’t groom or take care of her baby as well as a mother bat should. Her friend BD helped out, grooming the baby, sharing food with Lilith, and eventually even nursing the baby when Lilith got too sick to produce milk. After Lilith died, BD adopted the baby as though it was her own. By the time the study ended, BD was still caring for the baby bat.

We talked about spiders in the Antarctic in episode 221, and mentioned that Antarctica hasn’t always been a frozen wasteland of ice and snow. In a new study of fossils found in Antarctica, published in May of 2021, the first Antarctic amphibian skull has been identified. It lived in the early Triassic, not long after the end-Permian mass extinction 252 million years ago. It’s been named Micropholis stowi and is a new species of temnospondyl that was previously only known from South Africa. The skull, along with other fossils from four individuals, was discovered in the Transantarctic Mountains in 2017 and 2018, and the research team studied them from home during the 2020 pandemic lockdowns.

In news about humans and our extinct close relations, a new finding shows that Neanderthals and humans used the same type of tools. Researchers studied a child’s tooth and some stone tools, all found in a cave in the mountains of Palestine, and determined that the tooth was from a Neanderthal child, not a human. The tooth was discovered in 1928 but was in a private collection until recently, so no one had been able to study it before now. The tools are a specific type developed in Africa that have only been found associated with humans before. Not only that, but until this finding, there was no evidence that Neandertals ever lived so far south.

The child is estimated to have been about nine or ten years old, which is the age when you’re likely to lose a baby tooth as your adult teeth start growing in. I like to think about the child sitting next to their Mom or Dad, who were either creating new tools or using ones they’d already made to do something like cut up food for that evening’s dinner. Maybe the child was supposed to be helping, and they were, but they had a loose tooth and kept giving it a twist now and then, trying to get it to come out. Then, finally, out it popped and bounced onto the cave floor, where it was lost for the next 60,000 years.

Researchers have just announced that they’ve sequenced the genetic profile of a woman who lived in what is now Romania about 35,000 years ago. Judging from her skull shape and what is known about ancient humans in Europe, the team had assumed she would be rather restricted in her genetic diversity but that she would show more Neanderthal ancestry than modern humans have. Instead, they were surprised to find that the woman had much more genetic diversity than modern humans but no more Neanderthal genes than most human populations have these days.

This was a surprise because modern humans whose prehistoric ancestors migrated out of Africa show much less genetic diversity than modern humans whose ancestors stayed in Africa until modern times. Researchers have always thought there was a genetic bottleneck at some point during or not long after groups of humans migrated out of Africa around 80,000 years ago. Lots of suggestions have been made about what might have caused the bottleneck, including disease, natural disaster, or just the general hardship of living somewhere where humans had never lived before. A genetic bottleneck happens when a limited number of individuals survive long enough to reproduce—in other words, in this case, if so many people die before they have children that there are hardly any children left to grow up and have children of their own. To show in the general population as it does, the bottleneck has to be widespread.

Now researchers think the genetic bottleneck happened much later than 80,000 years ago, probably during the last ice age. Humans living in Europe and Asia, where the ice age was severe, would have had trouble finding food and staying warm.

I’m getting close to finishing the Strange Animals Podcast book, which I’ll talk about a little more in our Q&A episode later this week. It’s a collection of the best mystery animals we’ve covered on the podcast, along with some new mystery animals, and I’m working hard to update my research. If you remember back in episode 83, about mystery big cats, we discussed the Barbary lion, which was thought to be an extinct subspecies of lion that might not actually be extinct. Well, when I looked into it to see if any new information had turned up, I found more than I expected. I rewrote those paragraphs from episode 83 and I’ll read them here as an update:

Lions live mostly in Africa these days, but were once common throughout southern Asia and even parts of southern Europe. There even used to be a species called the American lion, which once lived throughout North and South America. It only went extinct around 11,000 years ago. The American lion is the largest species of lion ever known, about a quarter larger than modern African lions. It probably stood almost 4 feet tall at the shoulder, or 1.2 meters. Rock art and pieces of skin preserved in South American caves indicate that its coat was reddish instead of golden. It lived in open grasslands like modern lions and even in cold areas.

Much more recently, the Barbary lion lived in northern Africa until it was hunted to extinction in the area. The Barbary lion was the one that battled gladiators in ancient Rome and was hunted by pharaohs in ancient Egypt. It was a big lion with a dark mane, and was thought to be a separate subspecies of lion until genetic analysis revealed in 2006 that it wasn’t actually different from Panthera leo leo.

The last wild Barbary lion was sighted in 1956, but the forest where it was seen was destroyed two years later. The lions in a few zoos, especially in Ethiopia and Morocco, are descended from Barbary lions kept in royal menageries for centuries.

Lions are well known to live on the savanna despite the term king of the jungle, but they do occasionally live in open forests and sometimes in actual jungles. In 2012 a lioness was spotted in a protected rainforest in Ethiopia, and locals say the lions pass through the reserve every year during the dry season. That rainforest is also one of the few places left in the world where wild coffee plants grow. So, you know, extra reason to keep it as safe as possible.

Finally, we’ll finish with a mystery snake. In 1968, during the Vietnam War, the United States Naval Medical Research Unit discovered a small snake in central Vietnam. It was unusual enough that they decided to save it for snake experts to look at later, but things don’t always go to plan during wartime. The specimen disappeared somewhere along the line. Fortunately, there were photographs.

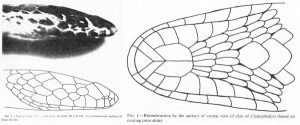

The photos eventually made their way to some biologists, and in 1994 a paper describing the snake as a new species was published by Wallach and Jones. They based their description on the photos, which were good enough that they could determine details like the number of scales on the head and jaw. They named it Cryptophidion annamense and suggested it was a burrowing snake based on its characteristics.

Other biologists thought Cryptophidion wasn’t a new species of snake at all. In 1996 a pair of scientists published a paper arguing that it was just a sunbeam snake. The sunbeam snake is native to Southeast Asia, including Vietnam, and can grow over 4 feet long, or 1.3 meters. It’s chocolate-brown or purplish-brown but has iridescent scales that give it a rainbow sheen in sunshine. It’s a constricting snake, meaning it squeezes the breath out of its prey to kill it, but it only eats small animals like frogs, mice, and other snakes. It’s nocturnal and spends a lot of its time burrowing in mud to find food.

Wallach and Jones, along with other scientists, argued that there were too many differences between the sunbeam snake and Cryptophidion for them to be the same species. But without a physical specimen to examine, no one can say for sure if the snake is new to science or not. If you live in or near Vietnam and find snakes interesting, you might be the one to solve this mystery.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!