Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 20:09 — 20.7MB)

Subscribe: | More

It’s update week! I call myself out for some mistakes, then catch us all up on new information about topics we’ve covered in the past. Then we’ll learn about the Nandi bear, a mystery animal that is probably not actually a bear.

Check out Finn and Lila’s Natural History and Horse Podcast on Podbean!

Check out the Zeng This! pop culture podcast while you’re at it!

A new species of Bird of Paradise:

Buša cattle:

Further reading/watching:

http://www.sci-news.com/biology/vogelkop-superb-bird-of-paradise-05924.html

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to dig into some updates to previous episodes! Don’t worry, it’ll be interesting. We’re also going to look at a mystery animal we haven’t examined before.

First, though, a big shout-out to Sir Finn Hayes, a long-time listener who has started his own podcast! It’s called Finn’s Natural History, although now I see it’s been renamed Finn and Lila’s Natural History and Horse Podcast, and you can find it on Podbean. I’ll put a link in the show notes. The great thing is, Finn is just ten years old but he and his younger sister Lila are already dropping knowledge on us about animals and plants and other things they find interesting. So give their podcast a listen because I bet you’ll like it as much as I do.

Before we get into the updates, let me call myself out on a few glaring mistakes in past episodes. In episode four, I called my own podcast by the wrong name. Instead of Strange Animals, I said Strange Beasties, which is my Twitter handle. In episode 29, I said Loch Ness was 50 miles above sea level instead of 50 feet, a pretty big difference. In episode 15 I called Zenger of the Zeng This! podcast Zengus, which is just unforgiveable because I really like that podcast and you’d think I could remember the cohost’s name. There’s a link to the Zeng This! podcast in the show notes. It’s a family-friendly, cheerful show about comics, movies, video games, and lots of other fun pop culture stuff.

If you ever hear me state something in the podcast that you know isn’t true, definitely let me know. I’ll look into it and issue a correction when appropriate. As they say on the Varmints Podcast, I am not an animal expert. I do my best, but sometimes I get things wrong. For instance, in episode 60, I said sirenians like dugongs and manatees have tails in place of hind legs like seals do, but sirenian tails actually developed from tails, not hind legs. Pinniped tails developed from hind legs and have flipper-like feet.

Anyway, here are some updates to topics we’ve covered in past episodes. It isn’t all-inclusive, mostly just stuff I’ve stumbled across while researching other animals.

In episode 47 about strange horses, I talked a lot about Przewalski’s horse. I was really hoping never to have to attempt that pronunciation again, but here we are. A new phylogenetic study published in February of 2018 determined that Przewalski’s horse isn’t a truly wild horse. Its ancestors were wild, but Przewalski’s horse is essentially a feral domestic horse. Its ancestors were probably domesticated around 5,500 years ago by the Botai people who lived in what is now northern Kazakhstan. The Przewalski’s horse we have now is a descendant of those domestic horses that escaped back into the wild long after its ancestors had died out. That doesn’t mean it’s not an important animal anymore, though. It’s been wild much longer than mustangs and other feral horses and tells us a lot about how truly wild horse ancestors looked and acted. Not only that, its wild ancestor is probably a different species or subspecies of the European wild horse, which was the ancestor of most other domestic horses. The next step for the team of researchers that conducted this study is figuring out more about the ancestors of domestic horses.

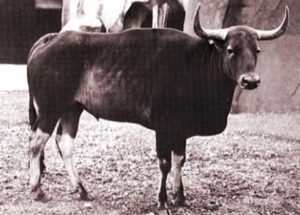

The mystery cattle episode also has an update. I didn’t mention Buša cattle in that episode, but I just learned something interesting about it. The Buša is a rare breed of domestic cow that developed in southeastern Europe. It’s a small, hardy animal well adapted to mountainous terrain, and it turns out that it’s the most genetically diverse breed of cattle out of sixty studied. The research team is working to help conserve the breed so that that genetic diversity isn’t lost.

Right after episode 61, where we talked about birds of paradise, researchers announced a new species of bird of paradise! The bird was already known to scientists, but they thought it was just a subspecies of the Superb Bird-of-Paradise. But new video footage of a unique mating dance helped researchers determine that this wasn’t just a subspecies, it was different enough to be its own species. It’s called the Vogelkop Superb Bird of Paradise, and the Superb Bird of Paradise is now called the Greater Superb Bird of Paradise to help differentiate the two species. I’ll put a link in the show notes to an article that has the video embedded if you want to watch it. It’s pretty neat.

In episode 25 we learned about Neandertals, and I said we didn’t have much evidence of them being especially creative by human standards. That was the case when I did my research last summer, but things have definitely changed. In February 2018 archaeologists studying cave paintings in Spain announced that paintings in at least three caves were made by Neandertals and not humans. The paintings have been dated to over 64,000 years old, which is 20,000 years before humans showed up in the area. The precise dating is due to a new and much more accurate dating technique called the uranium-thorium method, which measures the tiny deposits that build up on the paintings. So Neandertals might have been a lot more creative than we’ve assumed. Researchers are now looking at other cave art and artefacts like jewelry and sculptures to consider whether some might also have been made by Neandertals.

New studies about human migration out of Africa have also been published since our humans episode. Human fossils and stone tools found in what is now a desert in Saudi Arabia have been dated to 90,000 years ago, when the area was lush grassland surrounding a lake. Until this finding, researchers thought humans had not settled the area until many thousands of years later.

I think it was episode 27, Creatures of the Deeps, where I mentioned the South Java Deep Sea Biodiversity Expedition. Well, in only two weeks that expedition discovered more than a dozen new species of crustacean, including a crab with red eyes and fuzzy spines, collected over 12,000 animals to study, and learned a whole lot about what’s down there.

One thing I forgot to mention in episode 11 is that the vampire bat’s fangs stay sharp because they lack enamel. Enamel is a thin but very hard mineral coating found on the teeth of most mammals. It protects the teeth and makes them stronger. But vampire bats don’t chew hard foods like bones or seeds, and not having enamel means that their teeth are softer. I tried to find out more about this, like whether the bat does something specific to keep its teeth sharp, like filing them with tiny tooth files, but didn’t have any luck. On the other hand, I did learn that baby bats are born bottom-first instead of head-first, because this keeps their wings from getting tangled in the birthing canal.

Many thanks to Simon, who has sent me links to several excellent articles I would have missed otherwise. One is about the controversy about sea sponges and comb jellies, and which one was the ancestor of all other animals. We covered the topic in episode 41. Mere weeks after that episode went live, a new study suggests that sponges win the fight. Hurrah for sponges!

Simon also sent me an article about the platypus, which we learned about in episode 45. There’s a lot of weirdness about the platypus, so it shouldn’t be too surprising that platypus milk contains a unique protein so potently antibacterial that it could lead to the development of powerful new antibiotics. Researchers think the antibacterial properties are present in platypus milk because as you may remember, monotremes don’t have teats, just milk patches, and the babies lick the milk up. That means the milk is exposed to bacteria from the environment, so the protein helps keep platypus babies from getting sick.

Simon also suggests that in our mystery bears episode, I forgot a very important one, the Nandi bear! So this sounds like the perfect time to learn about the Nandi bear.

I had heard of the Nandi bear, but I had it confused with the drop bear, an Australian urban myth that’s used primarily to tease tourists and small children. But the Nandi bear is a story from Africa, and it might be based on a real animal.

It has a number of names in Africa and sightings have come from various parts of the continent, but especially Kenya, where it’s frequently called the chemosit. There are lots of stories about what it looks like and how it acts. Generally, it’s supposed to be a ferocious nocturnal animal that sometimes attacks humans on moonless nights, especially children. Some stories say it eats the person’s brain and leaves the rest of the body. That’s creepy. Also, just going to point this out, it’s extremely unlikely. Its shaggy coat is supposed to be dark brown, reddish, or black, and sometimes it will stand on its hind legs. When it’s standing on all four legs, it’s between three and six feet tall, or one to almost two meters. Its head is said to be bear-like in shape. Sometimes it’s described as looking like a hyena, sometimes as a baboon, sometimes as a bear-like animal. Its front legs are often described as powerful.

The first known sighting by someone who actually wrote down their account is from the Journal of the East Africa and Uganda Natural History Society, published in 1912. I have a copy and I’m just going to read you the pertinent information. The account is by Geoffrey Williams. The Nandi expedition Williams mentions took place in 1905 and 1906, and while it sounds like it was just a bunch of people exploring, it was actually a military action by the British colonial rulers who killed over 1,100 members of the Nandi tribe in East Africa after they basically said, hey, stop taking our land and resources and people. During the campaign, livestock belonging to the Nandi were killed or stolen, villages and food stores burned, and the people who weren’t killed were forced to live on reservations. Anyway, here’s what Geoffrey Williams had to say about the Nandi bear, which suddenly doesn’t seem quite so important than it did before I learned all that:

“Several years ago I was travelling with a cousin on the Uasingishu just after the Nandi expedition, and, of course, long before there was any settlement up there. We had been camped on the edge of the Escarpment near the Mataye and were marching towards the Sirgoit Rock when we saw the beast. There was a thick mist, and my cousin and I were walking on ahead of the safari with one boy when, just as we drew near to the slopes of the hill, the mist cleared away suddenly and my cousin called out ‘What is that?’ Looking in the direction to which he pointed I saw a large animal sitting up on its haunches not more than 30 yards away. Its attidue was just that of a bear at the ‘Zoo’ asking for buns, and I should say it must have been nearly 5 feet high. It is extremely hard to estimate height in a case of this kind; but it seemed to both of us that it was very nearly, if not quite, as tall as we were. Before we had time to do anything it dropped forward and shambled away towards the Sirgoit with what my cousin always describes as a sort of sideways canter. The grass had all been burnt off some weeks earlier and so the animal was clearly visible.

“I snatched my rifle and took a snapshot at it as it was disappearing among the rocks, and, though I missed it, it stopped and turned its head round to look at us. It is in this position that I see it most clearly in my mind’s eye. In size it was, I should say, larger than the bear that lives in the pit at the ‘Zoo’ and it was quite as heavily built. The fore quarters were very thickly furred, as were all four legs, but the hind quarters were comparatively speaking smooth or bare. This distinction was very definite indeed and was the first thing that struck us both. The head was long and pointed and exactly like that of a bear, as indeed was the whole animal. I have not a very clear recollection of the ears beyond the fact that they were small, and the tail, if any, was very small and practically unnoticeable. The colour was dark and left us both with the impression that it was more or less of a brindle, like a wildebeeste, but this may have been the effect of light.”

A couple of years later, in the same journal, a man saddled with the name Blayney Percival wrote about the Nandi bear. He said, “The stories vary to a very large extent, but the following points seem to agree. The animal is of fairly large size, it stands on its hind legs at times, is nocturnal, very fierce, kills man or animals.” Percival thought the differing stories referred to different animals, known or unknown. He wrote, “An example of a weird animal was the beast described to me in the Sotik country; the name I forget, but the description was very similar to that of the chimiset. Fair size—my pointer dog being given as about its size; stood on hind legs; was very savage. Careful inquiries and a picture of the ratel settled the matter, then out came the information that it was light on the back and dark below, points that would have settled it at once.” The ratel, of course, is the honey badger.

In 1958, cryptozoologist Bernard Heuvelmans wrote in his seminal work On the Track of Unknown Animals that the Nandi bear was probably based on more than one animal. Like Percival, he thought the different accounts were just too different. He thought at least some sightings were of honey badgers, while some were probably hyenas.

So if at least some accounts of the Nandi bear are of an unknown animal, what kind of animal might it be? Is it a bear? Do bears even live in Africa?

Africa has no bears now, but bear fossils at least three million years old have been found in South Africa and Ethiopia. Agriotherium africanum probably went extinct due to increased competition when big cats evolved to be fast, efficient hunters.

So it’s not likely that the Nandi bear is an actual bear. It’s also not likely it’s an ape of some kind, since apes are universally diurnal and the Nandi bear is described as nocturnal. Cryptozoologists have suggested all sorts of animals as a possible solution, but this episode is already getting kind of long so I’m not going to go into all of them. I’m just going to offer my own suggestion, which I have yet to see anywhere else, probably because it’s a bit farfetched. But hey, you never know.

The family of carnivores called Amphicyonidae are extinct now, as far as we know, but they lived throughout much of the world until about two million years ago. They’re known as bear-dogs and were originally thought to be related to bears, but are now considered more closely related to canids, possibly even the ancestors of canids. They are similar but not related to the dog-bears, Hemicyoninae, which are related to bears but which went extinct about 5 million years ago. Someone needs to sort out this bear-dog/dog-bear naming confusion.

Anyway, Amphicyonids lived in Africa, although we don’t have a whole lot of their fossils. The most recent Amphicyonid fossils we have date to about five million years ago and are of dog-sized animals that ate meat and lived in what are now Ethiopia and Kenya. Generally, Amphicyonids were doglike in overall shape but with a heavier bear-like build. They probably had plantigrade feet like bears rather than running on relatively small dog-like paws—basically, canids walk on their toes while bears walk on flat feet like humans. They were probably solitary animals and some researchers think they went extinct mainly because they couldn’t adapt to a changing environment and therefore different prey species, and couldn’t compete with smarter, faster pack hunting carnivores.

Maybe a species of Amphicyonid persisted in parts of Africa until recently, rarely seen but definitely feared for its ferocity. Probably not, because five million years is a long time to squeak by in an area with plenty of well-established carnivores. But maybe.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or whatever platform you listen on. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!