Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 17:05 — 19.0MB)

Thanks to Alexandra, Pranav, Eilee, Conner, and Joel for their suggestions this week!

Velella velella, or by-the-wind-sailor [photo from this page]:

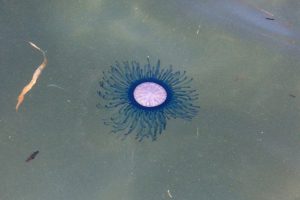

Porpita porpita, or the blue button [photo from this page]:

Cricetus cricetus, or the European hamster, next to a golden hamster:

Nasua nasua, or the South American coati [photo from this page]:

Mola mola, or the ocean sunfish:

Quelea quelea, or the red-billed quelea [photo from this page]:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going to learn a little bit about scientific names, and along the way we’re going to learn about several animals. Thanks to Alexandra, Eilee, Conner, Joel, and Pranav for their suggestions!

Alexandra inspired this episode by suggesting two animals, the by-the-wind-sailor and the blue button. Both are marine invertebrates that look superficially like jellyfish, but they’re actually colonial organisms. That means that although they look like a single animal, they’re actually made up of lots of tiny animals that live together and function as one organism.

The blue button is closely related to the by-the-wind-sailor and both are related to siphonophores. Both the blue button and the by-the-wind-sailor spend most of the time near or on the ocean’s surface and have a gas-filled chamber that helps keep them afloat, with stinging tentacles that hang down into the water, but both are made up of a colony of tiny animals called hydroids. Different hydroids have different functions, and all work together to find tiny food that will benefit the entire colony.

The blue button gets its name because its float is round and flat like a button, and often blue or teal in color. It’s quite small, only a little over an inch across, or about 3 cm, and its tentacles are not much longer. The by-the-wind-sailor is a little larger than the blue button, with a blue sail-shaped float that’s only a few inches across, or maybe 7 cm, with stinging tentacles of about the same size. The stings of both organisms aren’t very strong and aren’t dangerous to humans, but they do hurt, so it’s a good idea not to touch one. Since both can be very common in warm ocean waters and they sometimes get blown ashore by the wind in large numbers, it can be hard to avoid them if you’re visiting the beach at the wrong time. They can still sting you if they’re dead, too.

The by-the-wind sailor has the scientific name of Velella velella while the blue button’s scientific name is Porpita porpita. The term for a scientific name that contains the same words is a repeating scientific name, also called a tautonym or tautonymous name, and that’s the subject of this episode.

A scientific name is something we mention a lot but if you’re not sure what it means, it can sound confusing. Every organism with a scientific name has been described by a scientist, meaning it’s been studied and placed somewhere in the great interconnected web of life. The system of giving organisms scientific names is called binomial nomenclature. The first word of the name indicates which genus the organism belongs to, while the second word indicates what species it is. These are called generic and specific names. Some organisms also have a third word in their scientific name which indicates its subspecies.

The reason scientists use a complicated naming system is to make it easier for other scientists to know exactly what organism is being discussed. For example, let’s say a scientist has been studying hamsters in the wild to learn more about them, and publishes a paper about her observations. If she just calls the animal a hamster, someone reading it might assume she was talking about the hamster found in their part of the world, when the paper is actually about a totally different, although closely related, hamster that lives somewhere else. And that brings us to Pranav’s suggestion, the European hamster, whose scientific name is Cricetus cricetus [cry-SEE-tus].

The hamster most of us are familiar with is actually the golden hamster, also called the Syrian hamster, more properly called Mesocricetus auratus. That’s the most common species kept as a pet. We can learn from the different scientific names that the European hamster is in a different genus from the golden hamster, which usually means it’s pretty different in some significant ways.

The European hamster lives throughout parts of Eurasia, especially eastern Europe through central Asia, and used to be extremely common. It’s also called the black-bellied hamster because the fur on its underside is black, while the fur on its upper side is tan or brown with white markings. These days it’s critically endangered due to habitat loss and being killed by farmers who think it hurts their crops. It does eat seeds, vegetables, and some roots, but it also eats grass and many other plants that are considered weeds, as well as insects, including insects that farmers also don’t want in their gardens.

In many respects, the European hamster is a lot like the golden hamster. It carries food home to its burrow in its cheek pouches and stores food in a larder. It hibernates in cold weather but wakes up around once a week to have a snack from its larder, which honestly sounds like the best way to spend the winter. But the European hamster is larger than the golden hamster. Like, a lot larger. The golden hamster is maybe 5 inches long, or 13 cm, which is small enough that you can easily hold it in your hand. The European hamster grows up to 14 inches long, or 35 cm. That’s the size of a small domestic cat, but with a short little hamster tail and short little hamster legs.

Even though an organism’s scientific name only designates genus and species, and subspecies when applicable, it allows scientists to look up a more detailed family tree. Every genus is classified in a family and every family is classified in an order, and every order in a class, and every class in a phylum, and every phylum in a kingdom, and every kingdom in a domain. Almost all of the organisms we talk about in this podcast belong to the kingdom Animalia. The more of these categories an organism shares with another organism, the more closely related they are.

Conner suggested we learn more about the coati, which we talked about in episode 302. The South American coati’s scientific name is Nasua nasua [NAH-sue-uh]. It grows almost four feet long, or 113 cm, which makes it sound enormous, but half of its length is its long ringed tail. It lives in much of South America, especially the northern part of the continent.

The coati is related to the raccoon of North America, and the two animals’ scientific names can help us determine how closely they’re related. The common raccoon’s scientific name is Procyon [PROSE-eon] lotor, so we already know it belongs to a different genus than the coati. But both the genus Procyon and the genus Nasua are classified in the family Procyonidae. So we know they’re closely related, because they belong to the same family, but not as closely related as they’d be if they belonged to the same genus, so we can expect to see some fairly significant differences between the two animals.

The South American coati is diurnal, unlike the nocturnal raccoon. While female raccoons often live in small groups of a few animals that share the same territory, female coatis live in groups of up to 30 animals who forage for food together and are very social. The coati also doesn’t have a set territory. The male coati is completely solitary, while the male raccoon will also live in small groups of three or four animals. Both are omnivorous but the coati eats more fruit and insects than the raccoon does, and the coati doesn’t dunk its food in water the way the raccoon famously does.

The system of binomial nomenclature that we use today was developed by the Swedish botanist Carolus Linnaeus in 1735. We talked about some of his mistakes in episode 123. Linnaeus built on a system developed by a zoologist almost a century before him, but streamlined it and made it easier to use. In the 300 years since Linnaeus came up with his system, many other scientists have made changes to reflect increased knowledge about the natural world and how best to denote it.

I keep saying “organism” instead of “animal,” and that’s because all living organisms may be given a scientific name as they are described. This includes everything from humans to maple trees, from earthworms to harpy eagles, from bumblebees to mushrooms. Linnaeus originally included minerals in his classification system, but minerals don’t evolve the way living organisms do. One group that wasn’t given scientific names until 2021 are viruses. There’s still a lot of controversy as to whether viruses are technically alive or not, but giving them scientific names helps organize what we know about them.

Eilee suggested the ocean sunfish, which has the scientific name Mola mola. Because its scientific name is easy to say, and because there’s also a freshwater sunfish that isn’t related to the ocean sunfish, a lot of people just call it the mola-mola, or just the mola. We talked about it way back in episode 96, so we’re definitely due to revisit it.

The ocean sunfish doesn’t look like a regular fish. It looks like the head of a fish that had something humongous bite off its tail end. It has one tall dorsal fin and one long anal fin, and a little short rounded tail fin that’s not much more than a fringe along its back end. This isn’t even a real tail but part of the dorsal and anal fins. The sunfish uses the tail fin as a rudder and progresses through the water by waving its dorsal and anal fins the same way manta rays swim with their pectoral fins. Pectoral fins are the ones on the sides, while the dorsal fin is the fin on a fish’s back and an anal fin is a fin right in front of a fish’s tail. Usually dorsal and anal fins are only used for stability in the water, not propulsion. The ocean sunfish does have pectoral fins, but they’re tiny.

The ocean sunfish lives mostly in warm oceans around the world, and it eats jellies, small fish, squid, crustaceans, plankton, and even some plants. It has a small round mouth that it can’t close and four teeth that are fused to form a sort of beak. It also has teeth in its throat, called pharyngeal teeth. Its skin is thick and rough like sandpaper with a covering of mucus, and its bones are mostly cartilaginous. It likes to sun itself at the water’s surface, and it will float on its side like a massive fish pancake and let sea birds stand on it and pick parasites from its skin. This also helps it absorb heat from sunlight after it’s been hunting in deeper water.

The female ocean sunfish can lay up to 300 million eggs at a time. That is the most eggs known to be laid by any vertebrate. When the eggs hatch, the larval sunfish are only 2 ½ mm long. Once they develop into their juvenile form, they have little spines all around their thin end, which kind of make them look like tiny stars. If that seems weird, consider that the ocean sunfish is actually related to the pufferfish, although not very closely. The largest adult ocean sunfish ever reliably measured was 14 feet tall, or 4.3 meters, including the long fins, which is a whole lot bigger than 2 ½ mm.

Sometimes after an organism is initially described and named, later scientists learn more about it and determine that it doesn’t actually belong in the genus or family where it was initially placed. If it gets moved to a different genus, its scientific name also needs to change. Some organisms get moved a lot and their scientific names change a lot. But typically, the species name doesn’t change. That’s the case for a little bird from Africa.

Joel suggested a bird called the red-billed quelea [QUEE-lee-ya], whose scientific name is Quelea quelea. When Linnaeus described it in 1758, he thought it was a type of bunting, so he named it Emberiza quelea. Another scientist moved it into a new genus, Quelea, in 1850.

I’d never heard of the red-billed quelea, which is native to sub-Sarahan Africa, but it may actually be the world’s most numerous non-domesticated bird, with an estimated 1.5 billion birds alive at any given moment.

The red-billed quelea mainly eats grass seeds, and unlike the European hamster, it is actually a problem to farmers. The bird doesn’t know the difference between yummy grass seeds and yummy wheat, barley, milt, oats, sunflowers, and other food that humans eat. In fact, some researchers suggest that the bird has become incredibly numerous because it has all this great food to eat that was planted by people.

A flock of red-billed quelea birds can number in the millions. The flock flies until they find grassland or fields with food they like. The first birds land, the birds behind them land a little bit farther along, and so on until all the birds have landed and are eating. But by the time the last birds of the flock land, the first ones have eaten everything they can find, so they fly up and over the rest of the birds until they find fresh grass to land in again. This is happening constantly with the entire flock of millions of birds, so that from a distance the flock’s movement looks like a cloud of smoke rolling across a field.

The red-billed quelea also eats insects, mostly during nesting season. Insects and other small invertebrates like spiders are especially nutritious for nestlings.

The quelea is about the size of a sparrow, which it resembles in many ways, although it’s actually a member of the weaver bird family, Ploceidae. It grows less than five inches long, or about 12 cm, including its tail, and it’s mostly brown and gray. Its beak and legs are orangey-red, and during breeding season the male has a rusty-red head with a black mask on his face.

One subspecies of red-billed quelea is native to western and central Africa. Since it’s a subspecies, it has three words in its scientific name: Quelea quelea quelea.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!