Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 12:11 — 12.3MB)

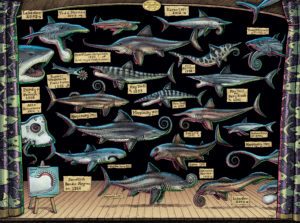

This week let’s learn about some ancestors of sharks and shark relatives that looked very strange compared to most sharks today!

Stethacanthus fossil and what the living fish might have looked like:

Two Falcatus fossils, female above, male below with his dorsal spine visible:

Xenacanthus looked more like an eel than a shark:

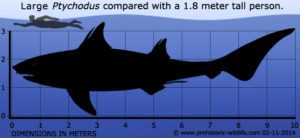

Ptychodus was really big, but not as big as the things that ate it:

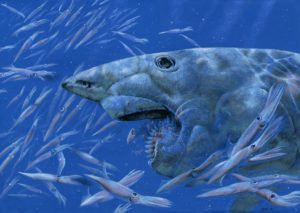

A Helicoprion tooth whorl and what a living Helicoprion might have looked like:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re going back in time again to learn about some animals that are long-extinct…but they’re not land animals. Yes, it’s a weird fish episode, but this one is about shark relatives!

The first shark ancestor is found in the fossil record around 420 million years ago, although since all we have are scales, we don’t know exactly what those fish looked like. The first true shark was called Cladoselache [clay-dough-sell-a-kee] and lived around 370 million years ago, at the same time as dunkleosteus and other massive armored fish. We covered dunkleosteus and other placoderms back in episode 33. Cladoselache grew up to four feet long, or 1.2 meters, and was a fast swimmer. We know Cladoselache ate fish because we have some fossils of Cladoselache with fish fossils in the digestive system—whole fish fossils, which suggests that cladoselache swallowed its prey whole. Cladoselache also had fin spines in front of its dorsal fins that made the fins stronger, but unlike its descendants, it didn’t have denticles in its skin. It didn’t have scales at all.

The denticles in shark skin aren’t just protection for the shark, they also strengthen the skin to allow for the attachment of stronger muscles. That’s why sharks are such fast swimmers.

[Jaws theme]

Stethacanthidae was a family of fish that went extinct around 300 million years ago. It was related to ratfish and their relatives, including sharks. Stethacanthus is the most well-known of the stethacanthidae. It grew a little over 2 feet long, or 70 cm, and was probably a bottom-dwelling fish that lived in shallow waters. It ate crustaceans, small fish, cephalopods, and other small animals.

We have some good fossils of various species of Stethacanthidae and they show one feature that didn’t get passed down to modern ratfish or sharks. That’s the shape of its first dorsal fin, the one that in shark movies cuts through the water just before something awful happens.

[Jaws theme again]

Stethacanthidae’s dorsal fin was really weird. It was shaped sort of like a scrub brush on a pedestal, with the bristles sticking upwards, which is sometimes referred to as a spine-brush complex. Researchers aren’t sure why its fin was shaped in such a way, but since it appears that only males had the oddly shaped fin, it was probably for display. It also had a patch of the same kind of short bristly denticles on its head. Males also had a long spine that grew from each pectoral fin that was probably also for display. Some researchers think the males fought each other by pushing head to head, possibly helped by the odd-shaped dorsal fin.

In the past, before researchers figured out that only the males had the strange dorsal fin, some people suggested that the fish may have used the fin as a sucker pad to attach to other, larger fish and hitch a ride. This is what remoras do. Remoras have a modified dorsal fin that is oval-shaped and acts like a sucker. The oval contains flexible membranes that the remora can raise or lower to create suction. The remora attaches to a larger animal like a shark, a whale, or a turtle and lets the animal carry it around. In return, the remora eats parasites from the host animal’s skin. But remoras aren’t related to sharks.

Other shark relatives had dorsal spines. Falcatus falcatus lived about the same time as Stethacanthus, around 325 million years ago. It grew up to a foot long, or 30 cm, and ate shrimp, fish, and other small animals. We have so many fossils of falcatus from the Bear Gulch Limestone deposits in Montana that we know quite a bit about it. It probably detected prey with electroreceptors on its snout like many modern sharks do, and it was probably a fast swimmer that could dive deeply. Its eyes are unusually large for a shark too. Females would have looked like a small, slender sharklike fish, but males had a spine that grew forward from just behind its head, sort of like a single bull’s horn. It’s called a dorsal spine and is actually a modified dorsal fin. It was probably for display, although males may have also used it to fight each other. We have a well preserved fossil of a pair of falcatus together, a male and female, where it looks like the female may be biting the male’s dorsal spine. Some researchers suggest the spine was used in a pre-mating ritual, but it’s probable that the fish just happened to die next to each other and no one was actually biting anyone.

Another shark relative with a dorsal spine is Hybodus, which grew up to 6 ½ feet long, or 2 meters. Hybodus was a successful genus of cartilaginous fish that lived from around 260 million years ago up to 66 million years ago. Researchers think its dorsal spine was used for defense since both males and females had the spine. Hybodus would have looked like a shark but its mouth was relatively small. It probably ate small fish and squid, catching them with the sharp teeth in the front of its mouth, but it also probably ate a lot of crustaceans and shellfish, which it crushed with the flatter teeth in the rear of its mouth.

Xenacanthus had a dorsal spine too, but it was a much different shark ancestor from the ones we’ve talked about so far. It lived until about 208 million years ago in fresh water. It grew to about three feet long, or one meter, and would have looked more like an eel than a shark. It was slender with an elongated body, and its dorsal fin was short but extended along the back down to the pointed tail. This suggests it probably swam like an eel, since eels have a similar fin structure. It probably ate crustaceans and other small animals.

Xenacanthus’s spine grew from the back of the skull and, unusually for a shark relation, it was made of bone instead of cartilage. Both males and females had the spine and some researchers suggest that it may have been venomous like a sting ray’s tail spine.

Rays are closely related to sharks, and if you want to see a fish that makes every single weird extinct shark look normal, just look at a sawfish. The sawfish is a type of ray and it’s alive today, although it’s endangered. I’m going to do a whole episode on rays pretty soon so I won’t go into detail, but the sawfish isn’t the only fish alive today with a long snout with teeth that stick out on either side. The sawshark is related to the sawfish but is actually a shark, not a ray. And there’s a third type of fish with a saw, related to both sawfish and sawsharks, called the Sclerorhynchidae. Sclerorhynchids went extinct around 55 million years ago and are considered part of the ray family, although they’re not ancestors of living rays. Sclerorhynchids grew around three feet long, or about a meter, and probably looked a lot like modern sawfish although with a rostrum, or snout, that was more pointed and less broad than most sawfish rostrums. The teeth that stuck out to either side were also relatively small. Researchers think Sclerorhynchids used their saws the same way modern sawfish and sawsharks do, to find small animals living on or near the bottom in shallow water and slash them to death before eating the pieces.

[Jaws theme again]

Most of the shark relatives we’ve talked about so far were pretty small, certainly compared to sharks like the great white or megalodon, which by the way we covered in episode 15 along with the hammerhead shark. But a shark called Ptychodus grew up to 33 feet long, or ten meters. It went extinct about 85 million years ago. Its dorsal fin had serrated spines and its mouth had lots and lots of really big teeth–up to 550 teeth, but they weren’t sharp. Instead, they were flattened with riblike folds that helped Ptychodus crush the mollusks it ate. It probably also ate squid and crustaceans, along with any carrion it might come across. It lived at the bottom of the ocean, but in relatively shallow areas where there were plenty of mollusks but not too many mosasaurs or other sharks that might treat Ptychodus as a nice big meal.

In episode 33, the one about dunkleosteus, we also talked about helicoprion and some of its relations. Helicoprion looked like a shark but was actually less closely related to true sharks than to ratfish. Helicoprion lived until about 250 million years ago and some researchers estimate it could grow up to 24 feet long, or 7.5 meters.

Instead of a weird dorsal fin, helicoprion had weird teeth. Weird, weird teeth. It had a tooth whorl instead of the regular arrangement of teeth, where its teeth grew in a spiral that seems to have been situated in the lower jaw. It looked like the blade of a circular saw. Now, this is bizarre but it’s not really all that much more bizarre than sawfish teeth, which aren’t even inside the mouth and stick out sideways. But the frustrating thing for researchers is that we still don’t have any helicoprion fossils except for the teeth whorls and part of one skull. Like most sharks and shark relatives, almost all of helicoprion’s skeleton was made of cartilage, not bone, and cartilage doesn’t fossilize very well. So even though helicoprion was widespread and even survived the Permian-Triassic extinction event, we don’t know what it looked like or what it ate or how exactly its tooth whorl worked. But I think it’s safe to say that it would not be good to be bitten by helicoprion.

[stop playing the Jaws theme omg]

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!

[Jaws theme again]