Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 13:21 — 14.6MB)

This week we’re examining the Tantanoola Tiger, a mystery animal that probably wasn’t a tiger…but what was it? This episode is rated two ghosts out of five for monster month spookiness! Thanks to Kristie for sharing her photos of the Tantanoola tiger!

Happy birthday to ME this week! I’ve decided to turn 25 again. That was a good year.

Further reading:

The grisly mystery of the murderous Tantanoola Tiger (Please note that the end of this article has some disturbing details not appropriate for younger readers. However, true crime enthusiasts will just shrug.)

Kristie and her kids reacting to the taxidermied Tantanoola Tiger:

Kristie’s picture of the taxidermied Tantanoola Tiger. WHO DID THIS TO YOU, TIGER?

The numbat is striped but too small to fit the description of the “tiger”:

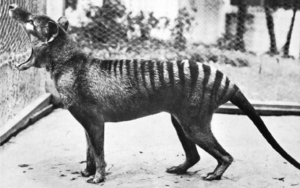

Our friend the thylacine, probably not strong enough to kill a full-grown sheep:

Tigers are really really really big. Also, don’t get this close to a tiger:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This past spring, when I was researching mysterious accounts of big cats spotted in Australia for episode 274, I considered including the Tantanoola Tiger. That was Kristie and Jason’s episode, and Kristie casually mentioned that she’d seen the stuffed Tantanoola tiger on display and wasn’t impressed. She even sent me pictures, which we’ll get to in a moment.

In the end, I decided the Tantanoola Tiger deserved its own episode, because it’s completely bonkers, and that it needed to be in monster month, because parts of the story are weird and creepy. I give it two ghosts out of five on our spookiness scale, so it’s not too spooky but it’s more than a little spooky.

The story starts in the southeastern part of South Australia at the very end of the 19th century. The little town of Tantanoola was home to a lot of sheep farmers, and in the early 1890s something was killing and eating sheep.

For years there had been rumors that a Bengal tiger had escaped from a traveling circus in 1884 and was living in the area, so once half-eaten sheep carcasses started turning up near Tantanoola, people assumed the tiger was to blame.

There was definitely something unusual killing sheep. Aboriginal shearers reported seeing an animal they didn’t recognize, something that frightened their dogs. Paw prints were found that measured over 4 inches across, or 11 cm, which is really big for a dog’s print although that’s what it resembled. It also happens to be a reasonable size for a small tiger, although a big tiger’s paw is usually more like 6 inches across, or almost 16 cm.

In 1892, a couple out driving in their buggy saw a striped animal cross the road ahead of them. They reported it as brown with stripes and a long tail. They estimated its length as three feet long not counting its tail, or about a meter, 5 feet long including the tail, or 1.5 meters. This is actually really short for a full-grown tiger. A big male Bengal tiger can grow more than ten feet long, or over 3 meters, including the tail, and even a small female Bengal tiger is about eight feet long, or 2.5 meters, including the tail.

There aren’t a lot of animals native to Australia that have stripes. The numbat has stripes and does live reasonably close to Tantanoola, although it was driven to extinction in the area by the late 19th century. But the numbat is only about 18 inches long, or 45 cm, including its tail, and it looks kind of like a squirrel. It eats insects, especially termites, which it licks up with a long, sticky tongue like a tiny anteater. It’s even sometimes called the banded anteater even though it’s a marsupial and not related to anteaters at all. Plus, it doesn’t eat very many ants. The female numbat doesn’t have a pouch, but while her babies are attached to her teats they’re protected by long fur and the surrounding skin, which swells up a little while the mother is lactating.

So the animal seen in 1892 probably wasn’t a numbat, but it also probably wasn’t actually a tiger. The people who saw it said it definitely wasn’t a dingo either.

In May 1893, a tiger hunt was organized but found nothing out of the ordinary, but in September of that year a farmer found huge paw prints after his dogs alerted him to an intruder during the night. The prints were over 4 inches across, or 11 cm, and this time a policeman took plaster casts of them. A zoologist at the Adelaide Zoo examined the casts and said that they weren’t tiger prints but were instead from some kind of canid.

The next month, in October, a farmer reported that he’d killed the Tantanoola tiger. But it wasn’t a tiger and wasn’t even any kind of wolf relation. Instead, it was a feral hog that had been killing his sheep for years and evading his attempts to kill it. The boar measured 9 feet from nose to tail, or 2.7 meters, and while it was probably responsible for some sheep killing, it wasn’t the Tantanoola tiger. The so-called tiger kept on killing sheep.

In August of 1894 a 17-year-old named Donald Smith saw a strange animal dragging a struggling sheep into the trees. The mystery animal was light brown with darker stripes and stood about two and a half feet high at the shoulder, or 75 cm, and was over four feet long, or 1.3 meters. Donald thought it was a tiger, although he’d never seen a tiger before. He said the stripes on its body were dull, but they were much more distinct on its head. When police and trackers arrived at the area later, after Donald alerted them, they found claw marks, bloody tufts of wool, and big paw prints.

Finally, the following August, two sharpshooters set out to hunt the so-called tiger and actually found it. It was just barely dawn when they saw what looked like a gigantic dog grab a sheep and wrestle it to the ground. One of the men shot the animal and killed it.

The Tantanoola tiger definitely wasn’t a tiger. It was more like a dog, but it was much bigger than any dog they knew and certainly much bigger than a dingo. It was three feet tall at the shoulder, or 91 cm, and 5 feet long, or 1.5 meters, including the tail. It was mostly dark brown with patches of lighter brown and gray, and yellowish legs. Its paws were over 4 inches across, or 11 cm. But it didn’t have stripes. It was identified as a wolf, although what kind of wolf varied. Suggestions included a European wolf, a Syrian wolf, or an Arabian wolf.

We still don’t know exactly what kind of wolf or related animal the animal was, but we do still have the stuffed specimen. It’s on display in the Tantanoola Hotel, which is where Kristie and her kids saw it several years ago. She took pictures and was kind enough to give me permission to use them, and please, I beg you, even if you’ve never clicked through to see any pictures I’ve posted before, please look at these. There are two, the reaction shot of Kristie and her kids looking at the Tantanoola tiger, and a picture of the tiger itself. You will laugh until you cry.

As we’ve mentioned a few times before, taxidermy requires a lot of work and artistic ability. Whoever stuffed and mounted the Tantanoola tiger lacked some of the artistic skills. It looks really goofy. Really, really goofy. But at least we have the body, although unfortunately it hasn’t been DNA tested so we still don’t know exactly what kind of wolf or wolf relation it is. But that’s not the only mystery.

In fact, there are three separate mysteries here. First, how did the wolf get to Australia? Second, what was the striped animal people were seeing? Third, what was killing sheep? Because even after the wolf was shot, sheep kept being killed and the striped animal was occasionally spotted.

One suggestion is that the striped animal was a thylacine. We’ve talked about it a few times before, most recently in episode 274. The thylacine was still alive in Tasmania in the 1890s, but it had been extinct in mainland Australia for about 3,000 years. It’s possible that someone brought a thylacine to mainland Australia where it escaped or was set loose, just as the wolf had to have been brought to Australia.

Then again, thylacines weren’t very strong. They mostly ate small animals, especially the Tasmanian native hen, which is about the size of a big flightless chicken with long legs. It was much smaller than a wolf and much, much smaller than a tiger. If there was a thylacine around Tantanoola at the time, it probably wasn’t the animal killing sheep.

Even though farmers had shot a huge feral hog and a wolf, neither of which belonged in Australia, sheep kept being killed. No one ever figured out what the striped animal was, and eventually it stopped being seen. The 19th century turned into the 20th century, and more and more sheep started disappearing—hundreds of them every year. In this case, though, they weren’t being eaten. They just disappeared.

Toward the end of 1910 the mystery was accidentally solved. Three hunters smelled an intense stench of death coming from some trees. It was so strong that they went to investigate. They found a path into the trees and came across something awful.

There were piles of dead sheep and lambs everywhere, dozens of them. They’d been skinned and the skins were hanging on wires strung through the trees. But the path continued, and when the hunters went farther, they found even more dead sheep.

It took a few weeks, but the police eventually tracked down the culprit, a local man who had been selling a lot of sheepskins on the sly for years despite not raising sheep himself. He’d killed thousands of sheep to sell their skins, leaving the bodies to just rot. He’d also done some other terrible crimes, so if you click through to read the article I’ve linked to in the show notes, please be aware that it’s not appropriate for younger readers. He’d also been convicted of sheep stealing in 1899, but in Victoria, not South Australia.

The sheep rustler wasn’t the Tantanoola tiger, because he was probably a good 140 miles away, or 225 km, when it was killing sheep. Besides, the so-called tiger actually ate the sheep it killed. But once he was caught and sentenced to jail, the Adelaide Evening Journal newspaper wrote about it with the headline “The Tiger Caged.”

As for the striped animal, tiger or not, we still have no idea what it was.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us for as little as one dollar a month and get monthly bonus episodes.

Thanks for listening!