Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 14:39 — 14.7MB)

This week we’ll look at an ancient mystery from the Middle East, a mythological dragon-like animal called the Mush-khush-shu, popularly known as the sirrush. Thanks to Richard J. for the suggestion!

The Ishtar Gate (left, a partial reconstruction of the gate in a Berlin museum; right, a painting of the gate as it would have looked):

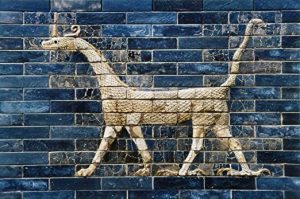

The sirrush of the Ishtar Gate:

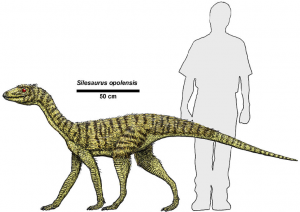

Two depictions of Silesaurus:

The desert monitor, best lizard:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week I have an interesting mystery animal suggested last September by Richard J. Thanks for the suggestion, Richard!

Before we learn about what the sirrush is, though, a quick note, or at least I’ll try to make it quick. I know a lot of people listen to Strange Animals as a fun escape from the everyday world, but right now the everyday world has important stuff going on that I can’t ignore. I want to make it clear to all my listeners that I fully support the Black Lives Matter movement, and I also support LGBTQ rights. Everyone in the whole world deserves respect and equality, but unfortunately right now we’re not there yet. We have to work for equality, all of us together.

If you’re not sure what to do to make the world a better place for everyone, it’s actually really simple. Just treat everyone the same way you want others to treat you and your friends. This sounds easy but when you meet someone who seems different from you it can be hard. If someone has different color skin from you, or speaks with an accent you find hard to understand, or uses an assistive device like a wheelchair, or if you just think someone looks or acts weird, it’s easy to treat that person different and even be rude, although you may not realize that’s what you’re doing at the time. When that happens, it’s always because you’re scared of the person’s differences. You have to consciously remind yourself that you’re being unreasonable and making that person’s day harder when it was probably already pretty hard, especially if everywhere they go, people treat them as someone who doesn’t fit in. Just treat them normally and both you and the other person will feel good at the end of the day.

So that’s that. I hope you think about this later even if right now you’re feeling irritated that I’m taking time out of my silly animal podcast to talk about it. Now, let’s find out what the sirrush is and why it’s such a mystery!

The sirrush is a word from ancient Sumerian, but it’s actually not the right term for this animal. The correct term is mush-khush-shu (mušḫuššu), but sirrush is way easier for me to pronounce. So we’ll go with sirrush, but be aware that that word is due to a mistranslation a hundred years ago and scholars don’t actually use it anymore.

My first introduction to the sirrush was when I was a kid and read the book Exotic Zoology by Willy Ley. Chapter four of that book is titled “The Sirrush of the Ishtar Gate,” and honestly this is about the best title for any chapter I can think of. But while Ley was a brilliant writer and researcher, the book was published in 1959. It’s definitely out of date now.

The sirrush is found throughout ancient Mesopotamian mythology. It usually looks like a snakelike animal with the front legs of a lion and the hind legs of an eagle. It’s sometimes depicted with small wings and a crest of some kind, sometimes horns and sometimes frills or even a little crown. And it goes back a long, long time, appearing in ancient Sumerian art some four thousand years ago.

But let’s back up a little and talk about Mesopotamia and the Ishtar Gate and so forth. If you’re like me, you’ve heard these names but only have a vague idea of what part of the world we’re talking about.

Mesopotamia refers to a region in western Asia and the Middle East, basically between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers. These days the countries of Iraq and Kuwait, parts of Turkey and Syria, and a little sliver of Iran are all within what was once called Mesopotamia. It’s part of what’s sometimes referred to as the Fertile Crescent in the Middle East. The known history of this region goes back five thousand years in written history, but people have lived there much, much longer. Some 50,000 years ago humans migrated from Africa into the area, found it a really nice place to live, and settled there.

Parts of it are marshy but it’s overall a semi-arid climate, with desert to the north. People developed agriculture in the Fertile Crescent, including irrigation, but many cultures specialized in fishing or nomadic grazing of animals they domesticated, including sheep, goats, and camels. As the centuries passed, the cultures of the area became more and more sophisticated, with big cities, elaborate trade routes, and stupendous artwork.

That includes the Ishtar Gate, which was one of the entrances to Babylon, the capital city of the kingdom of Babylonia. The city grew along the banks of the Euphrates River until it was one of the largest cities in the world by about 1770 BCE. Probably a quarter million people lived there in its heyday around the sixth century BCE, but it was a huge and important city for hundreds of years. It’s located in what is now Iraq not far from Baghdad. Babylon is actually the source of the Tower of Babel story in the book of Genesis. In that story, people decided to build a tower high enough to touch heaven, but God didn’t like that and caused the workers to all speak different languages and scattered them across the world. But that story may have grown from earlier stories from Mesopotamia, such as a Sumerian myth where a king asks the god Enki to restore a single language to all the people building an enormous ziggurat so the workers could communicate more easily.

Babylon means “gate of the gods,” and it did have many splendid gates in the massive walls surrounding the city. The ancient Greek historian Herodotus reported there were a hundred of these gates. One of these was the Ishtar Gate, built around 575 BCE. This wasn’t like a garden gate but an imposing and important entry point to the city. For one thing, it was the starting point of a half-mile religious procession held at the new year, which was celebrated at the spring equinox. The gate was dedicated to the goddess Ishtar and was more than 38 feet high, or 12 meters, and faced with glazed bricks. The background bricks were blue, with decorative motifs in orange and white, and there were rows of bas-relief lions, bulls, and sirrushes.

The sirrush was considered a sacred animal of both Babylon and its patron god, Marduk. It’s sometimes called a dragon in English, but from artwork that shows both Marduk and a sirrush, the sirrush was small, maybe the size of a big dog.

The question, of course, is whether the sirrush was based on a real animal or if it was an entirely mythical creature.

As I’ve said before in other episodes, every culture has stories that impart useful information—warnings, history lessons, and so forth. Every culture has monsters and mythological creatures of various kinds. That doesn’t mean those animals were ever thought of as real animals, although they might have taken on aspects of real animals. Think of it this way: You know the story of little red riding hood, right? Where the wolf meets the little girl on her way to Grandma’s house, then runs ahead and swallows the grandma whole and then tricks the little girl into coming close enough to swallow too? That story was never intended to be about a real, actual talking wolf but a warning to children to not talk to strangers. (There are plenty of other things going on in that story, but that’s the main takeaway.)

In other words, it’s quite likely that the sirrush was never meant to be anything but a creature of mythology, a glorious pet for a god. Then again, it’s also possible that it was based on a known creature, sort of like the talking wolf in Little Red Riding Hood is based on the real wolf that can’t talk.

And if that’s the case, what might that animal be?

There have been a lot of suggestions over the years. Willy Ley even suggested it was a modern dinosaur, possibly the mokele-mbembe. That was before the mokele-mbembe stories were widely recognized as hoaxes, as you may remember from way back in episode two. Other people have suggested it was an animal called a Silesaurus, which lived some 230 million years ago in what is now Poland.

Silesaurus grew up to around 7 ½ feet long, or 2.3 meters, and does kind of resemble the Ishtar Gate sirrush. It was slender and probably walked on all fours, with a long tail, long neck, and long legs. It had big eyes and probably mostly ate insects and other arthropods.

Silesaurus had traits found in dinosaurs but it wasn’t actually a dinosaur, although it belonged to a group of animals that were ancestral to dinosaurs. But it probably had one trait that puts it right out of the running to be the model for the sirrush, and that is that paleontologists think it had a beak. This wouldn’t have looked like a bird’s beak but more like a turtle’s, but it would have made the shape of the head very different from the snakelike head of the sirrush. Silesaurus probably pecked like a bird to grab insects. It also had stronger rear legs than front legs, as opposed to the sirrush that was depicted with birdlike rear legs but muscular lion-like front legs.

Silesaurus also lived 230 million years ago, so there’s just simply no way that it survived to modern times, no matter how much it superficially resembles the sirrush.

Ley also claims that the sirrush was the same dragon mentioned in the Bible, in a story called “Bel and the Dragon” in the extended Book of Daniel. Daniel slays the dragon by feeding it cakes made from hair and pitch. But there’s actually no connection between the sirrush and the dragon in this story.

One very specific detail of the sirrush is its forked tongue. This is a snakelike trait, of course, but some lizards also have forked tongues. Could the sirrush of mythology be based on a large lizard? For instance, a type of monitor lizard?

The largest monitor lizard species is the Komodo dragon, which can grow some ten feet long, or more than 3 meters. We talked about it in the Dragons episode a couple of years ago. But there are smaller, more common species that live throughout much of Africa, southern and southeastern Asia, and Australia. And that includes the Middle East.

The desert monitor was once fairly common throughout the Middle East, although it’s threatened now from habitat loss. It can grow up to five feet long, or 1.5 meters, and varies in color from light brown or grey to yellowish. Some have stripes or spots. It eats pretty much anything it can catch, and like many monitor species it’s a good swimmer. It hibernates in a burrow during the winter and also spends the hottest part of the day in its burrow. Like other monitor lizards it has a forked tongue and a flattish head. And it has a long tail, fairly long, strong legs, and a long neck.

If the sirrush was based on a real animal, it’s a good bet that that animal was the desert monitor. That doesn’t mean anyone thought the sirrush was a desert monitor or that we can point to the desert monitor and say, “Ah yes, the fabled sirrush, also called Mušḫuššu.” But people in Mesopotamia would have been familiar with this lizard, so a larger and more exaggerated version of it might have inspired artists and storytellers.

So…Boom! Looks like we solved that mystery. And we learned some history along the way. Definitely check the show notes for pictures of the Ishtar Gate, which has been partially reconstructed from bricks found in archaeological digs. It’s absolutely gorgeous. Also, the desert monitor is totally adorable.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or wherever you listen to podcasts. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!