Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 21:06 — 21.9MB)

Subscribe: | More

Thanks to Nicholas and Pranav for their suggestions which led to this episode about animals that are especially good at disguising themselves!

If you’d like to listen to the original Patreon episode about animal mimics, it’s unlocked and you can listen to it on your browser!

Don’t forget to contact me in some way (email, comment, message me on Twitter or FB, etc.) if you want to enter the book giveaway! Deadline is Oct. 31, 2020.

Further watching:

An octopus changing color while asleep, possibly due to her dreams

Crows mobbing an owl!

Baby cinereous mourner and the toxic caterpillar it’s imitating:

The beautiful wood nymph is a moth that looks just like bird poop when it sits on a leaf, but not when it has its wings spread:

The leafy seadragon, just hanging out looking like seaweed:

This pygmy owl isn’t looking at you, those are false eyespots on the back of its head:

Is it a ladybug? NO IT’S A COCKROACH! Prosoplecta looks just like a (bad-tasting) ladybug:

The mimic octopus:

A flower crab spider with lunch:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week let’s look at some masters of disguise. This is a suggestion from Nicholas, but we’ll also learn about how octopuses and other animals change colors, which is a suggestion from Pranav. Both these suggestions are really old ones, so I’m sorry I took so long to get to them. A couple of years ago we had a Patreon episode about animal mimics, so I’ll be incorporating parts of that episode into this one, but if you want to listen to the original Patreon animal mimics episode, it’s unlocked so anyone can listen to it. I’ll put a link to it in the show notes.

Most animals are camouflaged to some degree so that they blend in with their surroundings, which is also called cryptic coloration. Think about sparrows as an example. Most sparrows are sort of brownish with streaks of black or white, which helps hide them in the grass and bushes where they forage. Disruptive coloration is a type of camouflage that breaks up the outlines of an animal’s body, making it hard for another animal to recognize it against the background. Many animals have black eye streaks or face masks that help hide the eyes, which in turn helps hide where their head is.

But some animals take camouflage to the extreme! Let’s learn about some of these masters of disguise.

We’ll start with a bird. There’s a bird that lives in parts of South America called the cinereous mourner that as an adult is a pretty ordinary-looking songbird. It’s gray with cinnamon wing bars and an orange spot on each side. It mostly lives in the tropics. In 2012, researchers in the area found a cinereous mourner nest with newly hatched chicks. The chicks were orangey-yellow with dark speckles and had long feather barbs tipped with white. While the researchers were measuring the chicks and making observations, they noticed something odd. The chicks started moving their heads back and forth slowly. If you’ve ever seen a caterpillar moving its head back and forth, you’d recognize the chicks’ movements. And, as it happens, in the same areas of South America, there’s a large toxic caterpillar that’s fluffy and orange with black and white speckles.

It’s rare that a bird will mimic an insect, but mimicry in general is common in nature. We’ve talked about some animal mimics in earlier episodes, including the orchid mantis in episode 187 that looks so much like a flower that butterflies sometimes land on it…and then get eaten. Stick insects, also known as phasmids, which we talked about in episode 93, look like sticks. Sometimes the name just fits, you know? Some species of moth actually look like bird poop.

Wait, what? Yes indeed, some moths look just like bird poop. The beautiful wood nymph (that’s its full name; I mean, it is beautiful, but it’s actually called the beautiful wood nymph) is a lovely little moth that lives in eastern North America. It has a wingspan of 1.8 inches, or 4.6 cm, and its wings are quite lovely. The front wings are mostly white with brown along the edges and a few brown and yellow spots, while the rear wings are a soft yellow-brown with a narrow brown edge. It has furry legs that are white with black tips. But when the moth folds its wings to rest, suddenly those pretty markings make it look exactly like a bird dropping. It even stretches out its front legs so they resemble a little splatter on the edge of the poop.

But it’s not just insects that mimic other things. We’ve talked about frogfish before in episode 165. It has frills and protuberances that make it look like plants, rocks, or coral, depending on the species. The leafy seadragon, which is related to seahorses and pipefish, has protrusions all over its body that look just like seaweed leaves. It lives off the coast of southern and western Australia and grows over nine inches long, or 24 cm, and it moves quite slowly so that it looks like a piece of drifting seaweed. Not only are the protuberances leaf-shaped, they’re green with little dark spots, or sometimes brown, while the body can be green or yellowish or brown like the stem of a piece of seaweed.

Many animals have false eyespots, which can serve different purposes. Sometimes, as in the eyed click beetle we talked about in episode 186, the false eye spots are intended to make it look much larger and therefore more dangerous than it really is. Sometimes an animal’s false eyespots are intended to draw attention away from the animal’s head. A lot of butterflies have false eyespots on their wings that draw attention away from the head so that a predator will attack the wings, which allows the butterfly to escape. Some fish have eyespots near the tail that can make a predator assume that the fish is going to move in the opposite direction when startled.

Even some species of birds have false eyespots, including many species of pygmy owl. The Northern pygmy owl is barely bigger than a songbird, just six inches tall, or 15 cm. It lives in parts of western North America, usually in forests although it also likes wetlands. It’s mostly gray or brown with white streaks and speckles, but it has two black spots on the back of its head, fringed with white, that look like eyes. Predators approaching from behind think they’ve been spotted and are being stared at.

But some larger birds of prey have false eyespots too, including the American kestrel and northern hawk owl. What’s going on with that?

You’ve probably seen or heard birds mobbing potential predators. For instance, where I live mockingbirds will mob crows, while crows will mob hawks. The mobbing birds make a specific type of angry screaming call while divebombing the predator, often in groups. They mostly aim for the bird’s face, especially its eyes, in an attempt to drive it away. This happens most often in spring and summer when birds are protecting their nests. Researchers think the false eyespots that some birds of prey have help deflect some of the attacks from other birds. The mobbing birds may aim for the false eyespots instead of the real eyes. Despite its small size, the northern pygmy owl will eat other birds, and it’s also a diurnal owl, meaning it’s most active during the day, and it does sometimes get mobbed by other birds.

Sometimes, instead of blending in to its surroundings, an animal’s appearance jumps out in a way that you’d think would make it easy to find and eat. But like the cinereous mourner chicks mimicking toxic caterpillars, something in the mimic’s appearance makes predators hesitate.

A genus of cockroaches from the Philippines, Prosoplecta, have evolved to look like ladybugs, because ladybugs are inedible to many predators. But cockroaches don’t look anything like ladybugs, so the modifications these roaches have evolved are extreme. Their hind wings are actually folded up and rolled under their carapace in a way that has been found in no other insect in the world. The roach’s carapace is orangey-red with black spots, just like a ladybug.

In the case of a lot of milkweed butterfly species, including the monarch butterfly, which are all toxic and which are not related to each other, researchers couldn’t figure out at first why they all look pretty much alike. Then a zoologist named Fritz Müller suggested that because all the butterflies are toxic and all the butterflies look alike, predators who eat one and get sick will afterwards avoid all the butterflies instead of sampling each variety. That’s called Mullerian mimicry.

A lot of insects have evolved to look like bees, wasps, or other insects with powerful stings. The harmless milksnake has similar coloring to the deadly coral snake. And when the mimic octopus feels threatened, it can change color and even its body shape to look like a more dangerous animal, such as a sea snake.

And that brings us to the octopus. How do octopuses change color? Is it the same in chameleons or is that a different process? Let’s find out and then we’ll come back to the mimic octopus.

We’ve talked about the octopus in many episodes, including episodes 100, 142, and 174, but while I’ve mentioned their ability to change color before, I’ve never really gone into detail. Octopuses, along with other cephalopods like squid, have specialized cells called chromatophores in their skin. A chromatophore consists of a sac filled with pigment and a nerve, and each chromatophore is surrounded by tiny muscles. When an octopus wants to change colors, its nervous system activates the tiny muscles around the correct chromatophores. That is, some chromatophores contain yellow pigment, some contain red or brown. Because the color change is controlled by the nervous system and muscles, it happens incredibly quickly, in just milliseconds.

But that’s not all, because some species of octopus also have other cells called iridophores and leucophores. Iridophores are layers of extremely thin cells that can reflect light of certain wavelengths, which results in iridescent patches of color on the skin. While the octopus can control these reflections, it takes a little longer, several seconds or sometimes several minutes.

Leucophores are cells that scatter light, sort of like a mirrored surface, which doesn’t sound very helpful except when you remember how light changes as it penetrates the water. Near the surface, with full spectrum light from sunshine, the leucophores just appear like little white spots. But water scatters and absorbs the longer wavelengths of light more quickly than the shorter wavelengths. We’ve talked about this before here and there, mostly when talking about deep-sea animals.

To make it a little simpler, think of a rainbow. A rainbow is caused when there are a lot of water droplets in the air. Light shines through the droplets and is scattered, and the colors are always in the same pattern. Red will always be on the top of the rainbow because it has the longest wavelength, while violet, or purple, will always be on the bottom because it has the shortest wavelength. The same thing happens when sunlight shines into the water, but it doesn’t form a rainbow that we can see. Red light is absorbed by the water first, which is why so many deep-sea animals are unable to perceive the color red. There’s no reason for them to see it, so there’s no need for the body to put effort into growing receptors for that color.

Blue, by the way, penetrates water the deepest. That’s why clear, deep water looks blue. Solid particles in the water also affect how light scatters, so it can get complicated. But to get back to an octopus with leucophores, the leucophores reflect the color of the light that shines on them. So if an octopus is deeper in the water and the light shining on it is mostly in the green and blue spectrum, the leucophores will reflect green and blue, helping make the octopus look sort of invisible.

But wait, it gets even more complicated, because some octopuses can also change the texture of the skin. Sometimes that just means it can make its skin bumpy to help it blend in with rocks or coral, but some species can change the shape of the skin more drastically.

We still don’t fully understand how cephalopods know what colors they should change to. While octopuses mostly have good eyesight, at least some species are colorblind. But they can still match the background colors exactly. Some preliminary research into cuttlefish skin appears to show that the cuttlefish has a type of photosensor in the skin that allows it to sense light wavelengths and brightness without needing to use its eyes. Basically the skin acts like its own eye. This is getting weirder and weirder, but that happens when we talk about cephalopods because they are peculiar and fascinating animals. In 2019, marine biologists released footage of a captive octopus changing colors in her sleep. Some researchers think she may have been dreaming, and her dream prompted the color changes.

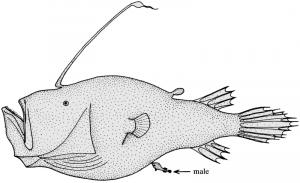

Let’s get back to the mimic octopus now that we’ve learned the basics of how octopuses change color. The mimic octopus lives throughout much of the Indo-Pacific, especially around Indonesia, and has an armspan of about two feet across, or 60 cm. It generally lives in shallow, murky water, where it forages for small crustaceans and occasionally catches small fish. It’s usually light brown with darker brown stripes, but it’s good at changing both its color and its shape to mimic other animals.

So far, researchers have documented it mimicking 15 other animals, including a sea snake where it hides all but two of its legs, a lion fish where it holds its legs out to look like spines, jellyfish, sting rays, frogfish, starfish, sponges, tube-worms, flatfish, and even a crab. It actually imitates a crab in order to approach other crabs, which it then grabs and eats. So obviously it’s not using its mimicry ability randomly. It will imitate a sea snake if it feels threatened by an animal that is eaten by sea snakes, for instance. And it was only discovered in 1998 and hasn’t been studied very well yet.

Unfortunately, the mimic octopus is rare to start with and threatened by pollution and habitat loss. Once it was discovered, people immediately wanted to own them. But the mimic octopus doesn’t do well in captivity, usually dying within weeks or even days. Even octopus experts have trouble keeping them alive for very long. One expert reported that the mimic octopus is incredibly shy and spends most of its time hiding deep under the sand. It’s mostly active at night and doesn’t like bright light. It’s incredibly sensitive to temperature changes, water quality, and even the type of salt used in saltwater aquariums, and most importantly, he reported that in captivity, it doesn’t do any imitating.

Chameleons are also famous for their ability to change color and pattern, but not every species can do so. The ones who can use a very different process for color changing compared to octopuses. The chameleon has a layer of skin that contains pigments with a layer beneath that contains crystals of guanine, a reflective molecule that’s used in cosmetics to make things look shimmery, like nail polish. The chameleon can move the crystals to change the way light reflects off them, which affects the color, especially when combined with the pigments in the upper layer of skin. The color change takes about 20 seconds and different species are able to change into different colors and patterns.

Not all mimics use appearance. A number of moths are toxic to bats, but it’s no use evolving bright colors to advertise their toxicity to predators who use echolocation to hunt. Instead, the moths generate high-pitched clicks that the bats hear, recognize, and avoid. And naturally, some non-toxic moths also generate the same sounds to mimic the toxic moths.

Let’s finish with a tiny spider that also changes color. It’s called the white crab spider or the goldenrod crab spider or the banana crab spider, or just the flower spider. It’s a small, common spider that lives throughout the northern hemisphere. You’ve probably seen a few of them in your time, probably when you’re leaning down to sniff a flower. It hangs out on flowers and can be white or yellow in color. A big female can be 10 mm long, not counting her legs, while males are barely half that size. They’re called crab spiders because they often run sideways like a crab. The flower spider doesn’t build a web. Instead, it just sits on a flower.

The male flower spider climbs around from flower to flower, looking for a mate. The female generally stays put on a particular flower until it fades, and then she’ll find a new one. If she moves from a yellow flower to a white one, or vice versa, she can change color to match, but it’s not a quick process. It takes at least ten days and sometimes up to 25 days to change from white to yellow, since the spider has to secrete yellow pigment into its cells, while changing from yellow to white usually takes less than a week. If she’s on a flower that is another color, she’ll usually remain white. Only the female can change color, and some females may have small red or pink markings that don’t change color. The male is usually yellow or off-white in color.

The flower spider is so well camouflaged that it can be hard to spot even if you’re looking for it. It eats butterflies and moths, bees, and other insects that visit the flowers. Males will also eat pollen. Its venom is especially toxic to bees, although it’s harmless to humans. It really likes to eat bumblebees. Its first pair of legs are longest and curve forward to make it easier for the spider to grab a bumblebee and sink its fangs into it. Meanwhile, the bumblebee has black and yellow stripes to advertise to potential predators that it will sting, but that doesn’t help it when it comes to the little crab spider. Danger in the bee world!

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Don’t forget to contact me if you want to enter the book giveaway contest, which will run through October 31, 2020! If you want to enter, just let me know by any means you like.

Thanks for listening!