Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 14:14 — 14.7MB)

Thanks to Phoebe for suggesting the tarsier, this week’s strange and interesting primate!

Further Reading:

Decoding of tarsier genome reveals ties to humans

Long-lost ‘Furby-like’ Primate Discovered in Indonesia

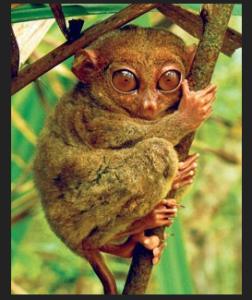

Tarsiers look like weird alien babies:

A tarsier nomming on a lizard:

A tarsier nomming on an insect:

The pygmy tarsier and someone’s thumb:

There’s probably not much going on in that little brain:

Show Transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

This week we’re looking at a weird and amazing little primate, but it’s not a monkey or ape. It’s the tarsier, with thanks to Phoebe who suggested it. It’s pronounced tarsiAY or tarsiER and both are correct.

The tarsier is such a little mess that until relatively recently scientists weren’t even completely certain it was a primate. A 2016 genetic study determined for sure that it is indeed a primate even though it differs in many ways from all other primates alive. For instance, it’s a carnivore. Most primates are herbivores and some are omnivores, including humans and chimpanzees, but only the tarsier is an obligate carnivore. That means it has to eat meat and only meat, whether it’s invertebrates, birds, reptiles, or small mammals like rodents.

Scientists divide primates into two groups informally, into wet-noses and dry-noses. Wet-nose doesn’t refer to a nose that’s runny but to a nose that stays moist, like a dog’s nose. This splits along the same lines as simians and prosimians, another way to group primates. Humans and other apes, along with monkeys, are simians, and also dry-noses. If you’re not sure if that’s accurate, just touch the end of your nose. Make sure you’re not standing in the rain or just got out of the bathtub, though. All other primates are wet-noses, and also prosimians, except for the tarsier. The tarsier is sort of in between. It’s grouped with the wet-nose primates, but it turns out to be more closely related to the dry-nose primates than the wet-noses. Also, its nose is actually dry.

One interesting difference between prosimians and simians concerns vitamin C. Vitamin C is found in a lot of foods, but especially in fruit and vegetables. If you don’t have any vitamin C in your diet, you will eventually die of scurvy like an old pirate, so make sure to eat plenty of fruit and vegetables. But most animals don’t need to eat foods containing vitamin C because their bodies already produce the vitamin C they need. Humans, apes, and monkeys have to worry about scurvy but prosimians don’t. But the tarsier does need vitamin C even though it’s a prosimian. A lot of researchers think the tarsier should be grouped with the simians, not prosimians.

The tarsier currently lives only in southeast Asia, mostly on forested islands, although tarsier fossils have been found throughout Asia, Europe, and North America. Genetic studies also indicate it probably started evolving separately from other primates around 55 million years ago in what is now China.

As it happens, we have a fossil that appears to be an early ancestor of the tarsier. Archicebus achilles was discovered in 2003 and studied for an entire decade before it was described in 2013, and it lived about 55 million years ago in what is now central China. It looks a lot like a tiny tarsier, but with smaller eyes that suggest it was active during the day. Its feet were shaped like a monkey’s, though, not like a tarsier’s feet. It probably only weighed about an ounce, or 28 grams. That’s about the same weight as a pencil. It had sharp little teeth and probably ate insects. So far the 2003 specimen is the only one found, but it’s remarkably complete so researchers have been able to learn a lot about it. If I’d been one of the scientists studying it, there is no way I could have waited ten whole years to tell people about it. I’d have studied it for like six months and then thought, “Okay, good enough, HEY EVERYONE LET ME TELL YOU ABOUT THIS COOL ANIMAL.”

The tarsier is nocturnal and has enormous eyes to help it see better in the dark. Its eyes are so big and round, and frankly the tarsier is not the brainiest animal, that its eyes are actually bigger than its brain. The tarsier also has mouse-like ears, long fingers and toes with sucker-like discs at the end to help it grip branches, and an extremely long tail that’s scaly on the underside. It spends almost its whole life in trees, where it climbs and jumps from branch to branch. When it climbs up a tree, it presses its long tail against the trunk to help it balance.

It’s not a big animal, though. A typical tarsier measures about six inches long, or 15 cm, from the top of its little round head to the bottom of its bottom, not counting its tail. Its tail can be almost a foot long, or 25 cm, though, and its hind legs are also extremely long, about as long as the tail. Its body is rounded with short plush fur, usually brown, gray, or dark gold in color.

With its big eyes and chonky body, if you wrapped up a tarsier in a little robe so you can’t see how small its ears are and how long its legs and tail and fingers are, it would kind of look like a miniature baby Yoda guy from that Mandalorian TV show. Someone please do that. Also, it kind of looks like a cute and furry Gollum from the Lord of the Rings movies.

Unlike other primates, the tarsier can turn its head 180 degrees in both directions. Basically it can turn its head like an owl. This is helpful because its eyes are so big it can’t move them. It can only look straight ahead, so it needs to be able to move its head all around instead. This is actually the same for the owl, too.

The tarsier mostly eats insects, but it will eat anything it can catch, including venomous snakes. It doesn’t just eat the meat, though. It eats just about everything, including bones. It has a wide mouth and strong jaws and teeth, and it’s so agile that it’s been observed to jump up and catch a bird as it flies past. Current speculation is that the tarsier gets enough vitamin C from the insects it eats that it doesn’t need to eat fruit, but no one knows for sure yet. Some species of bat can’t synthesize vitamin C in the body and have to get it from their diet, which is made up of insects.

We talked about the tarsier a little in episode 43, about the Chinese ink monkey, and also way back in episode eight, the strange recordings episode, because the tarsier can communicate in ultrasound [not infrasound]—sounds too high for humans to hear. It has incredibly acute hearing and often hunts by sound alone. Researchers speculate that not only can the tarsier avoid predators by making sounds higher than they can hear, it can also hear many insects that also communicate in ultrasound. As an example of how incredibly high-pitched their voices are, the highest sounds humans can hear are measured at 20 kilohertz. The tarsier can make sounds around 70 kh and can hear sounds up to 91 kh.

The tarsier also makes sounds humans can hear. Here’s some audio of a spectral tarsier from Indonesia:

[tarsier sound]

Some species of tarsier are social, some are more solitary. All are shy, though, and they don’t do well in captivity. Unfortunately, because the tarsier is so small and cute and weird-looking, some people want to keep them as pets even though they almost always die quite soon. As a result, not only is the tarsier threatened by habitat loss, it’s also threatened by being captured for the illegal pet trade. Fortunately, conservation efforts are underway to protect the tarsier within large tracts of its natural habitat, which is also beneficial for other animals and plants.

The smallest species is the pygmy tarsier, which is only found in central Sulawesi in Indonesia, in high elevations. It’s four inches long, or 10.5 cm, from head to butt. You measure tarsiers like you measure frogs. It’s basically the size of a mouse but with a really long tail and long legs and big huge round eyes and teeny ears and a taste for the flesh of mortals. Or, rather, insects, since that’s mostly what it eats.

For almost a century people thought the pygmy tarsier was extinct. No one had seen one since 1921. Then in 2000, scientists trapping rats in Indonesia caught a pygmy tarsier. Imagine their surprise! Also, they accidentally killed it so I bet they felt horrible but also elated. It wasn’t until 2008 that some live pygmy tarsiers were spotted by a team of scientists who went looking specifically for them. This wasn’t easy since tarsiers are nocturnal, so they had to hunt for them at night, and because the wet, foggy mountains where the pygmy tarsier lives are really hard for humans to navigate safely. It took the team two months, but they managed to capture three of the tarsiers long enough to put little radio collars on them to track their movements.

One of the things Phoebe wanted to know about tarsiers is if there are any cryptids or mysteries associated with them. You’d think there would be, if only because the tarsier is kind of a creepy-cute animal, but I only managed to find one kinda-sorta tarsier-related cryptid.

According to a 1932 book called Myths and Legends of the Australian Aboriginals, a little red goblin creature lives in trees in some parts of Australia, especially the wild fig tree. It’s called the yara-ma-yha-who and it looks sort of like a frog but sort of like a monitor lizard. It’s bright red and stands around four feet tall, or 1.2 meters, with skinny arms and legs. The ends of its fingers and toes are cup-shaped suckers. Its head is large with a wide frog mouth and no teeth.

When a person comes along, the yara-ma-yha-who drops down from its tree and grabs them by the arm. It uses the suckers on its fingers and toes to drain blood from their arm, then swallows the person whole. Then later it horks them back up, but they’re smaller than before and their skin is starting to turn red. Eventually the person turns into a yara-ma-yha-who, unless they manage to escape in time.

Some cryptozoologists speculate that the yara-ma-yha-who may be based on the tarsier. The tarsier has never lived in Australia, but it does live in relatively nearby islands. Most tarsier species do have toe pads that help them cling to branches, but frogs also have toe pads and frogs are found in Australia. Likewise, by no stretch of the imagination is the tarsier bright red, four feet tall, toothless, or active in the daytime. It’s more likely the legend of the yara-ma-yha-who is inspired by frogs, snakes, monitor lizards, and other Australian animals, not the tarsier. But just to be on the safe side, if you live in Australia you might want to walk around wild fig trees instead of under them.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!