Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 12:28 — 14.3MB)

Thanks to Elaine for suggesting one of our long-tailed birds this week!

Happy birthday to Jasper!! Have a great birthday!

Further reading:

Fossil of Ancient Long-Tailed Bird Found in China

All adult scissor-tailed flycatchers have long tails:

The long-tailed sylph male is the one with the long tail:

The long-tailed widowbird male has a long tail:

The long-tailed widowbird female has a short tail:

The pin-tailed whydah male has a long tail:

A pin-tailed whydah baby (left) next to a common waxbill baby (right):

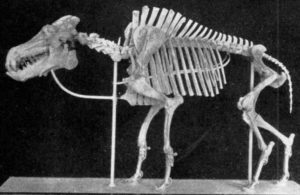

Kompsornis longicaudus had a really long tail:

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw. This week is a short episode all about little birds with really long tails. The tails are longer than the episode. Thanks to Elaine for suggesting one of the birds we talk about today!

But before we start learning about birds, we have a birthday shout-out! Happy birthday to Jasper, who has the best name and who will hopefully have the best birthday to go along with it!

Let’s start with Elaine’s suggestion, the scissor-tailed flycatcher. I’m embarrassed to admit that Elaine suggested this bird way back in 2020, so it’s about time we talked about it.

The scissor-tailed flycatcher lives in south-central North America during the summer, especially Texas and Oklahoma, and migrates to parts of Mexico and Central America in winter. It’s pale gray with black and white wings and tail, and salmon pink markings on its sides and under its wings. It also has a really long tail. It gets the name scissor-tail because its tail is so long and forked that it’s sort of the shape of an open pair of scissors. The male’s tail is typically longer than the female’s, longer than the rest of its body. The bird is about the size of an average songbird, with a body length of about 5 inches, or 13 centimeters, but with a tail that can increase its overall length to over 14 inches, or 36 cm.

The scissor-tailed flycatcher prefers open areas like pastures and fields, where there’s lots of space but some brush, trees, or fences nearby to perch in. It mostly eats insects, but it will also eat berries, especially in winter. It’s related to kingbirds and pewees and will even hybridize with the western kingbird where their ranges overlap. Its long tail is partly for display, but mostly it helps the bird maneuver in midair as it chases insects, or hover in midair as it looks around for an insect to catch. It especially likes grasshoppers, and when it catches one, it will usually kill it before eating it by smashing it against a tree limb or other perch.

Another little bird with a long tail is the long-tailed sylph, which is a type of hummingbird! It lives on the eastern slopes of the Andes Mountains in northwestern South America, mostly along forest edges, in gardens, grasslands, and other mostly open areas. It migrates to different parts of the mountains at different times of year to follow the flowering of its favorite plants. It’s larger than many species of hummingbird even if you don’t count the tail.

It eats nectar like other hummingbirds do, but also eats tiny insects and spiders. Its bill is black and not very long compared to most of its relations. Sometimes it will jab the tip of its bill straight through the base of a flower to get at the nectar, instead of inserting it into the flower like other hummingbirds do, and while it can hover, sometimes it perches to feed instead.

Both the male and female long-tailed sylph are a beautiful metallic blue and green in color, although the male is brighter and has purplish-brown wings. The female is about 4 inches long, or 10 cm, including her tail, and while the male is about the same size as the female, his tail is really long—up to 4.5 inches long, or 12 cm. His tail is forked like the scissor-tailed flycatcher’s, but unlike the flycatcher, the sylph’s tail makes it harder for the bird to fly. During breeding season the male attracts a mate by flying in a U-shaped pattern that shows off his tail and his flying ability.

The male long-tailed widowbird also attracts a mate with a flying display to show off his long tail. It lives in grasslands in a few parts of Africa, with the biggest population in South Africa. It forages in small flocks looking for seeds, and it also eats the occasional insect or spider. It’s a sparrow-like bird only about 4 inches long, or 10 cm, not counting its tail. The female is mostly brown with darker streaks and has a short tail. The male is black with red and white patches on the shoulders of his wings, called epaulets. His coloring, including the epaulets, is almost identical to that of a totally unrelated bird, the red-winged blackbird of North America, but he has something the blackbird doesn’t: a gigantically long tail.

The male widowbird’s tail is made up of twelve feathers, and about half of them grow up to 20 inches long. That’s nearly two feet long, or half a meter. Like the long-tailed sylph, the long-tailed widowbird’s tail actually makes it harder for him to fly. If it’s raining, he can’t fly at all. Fortunately for him, outside of the breeding season his tail is much shorter. During display flights, he spreads his tail feathers to show them off better and flies very slowly. Males with the longest tails attract the most females.

Similarly, the pin-tailed whydah is another little sparrow-like bird where the male grows a really long tail to attract females. It lives in grasslands, savannas, and open woodlands in sub-Saharan Africa, which just means south of the Sahara Desert. It mostly eats seeds.

During breeding season, the male is a striking pattern of black and white with a bright orangey-red bill and really long tail plumes. He’s about the size of the long-tailed widowbird but his tail grows about 8 inches long, or 20 cm. The female is brown with darker streaks and looks a lot like a sparrow, although it’s not related to sparrows. To impress a female, the pin-tailed whydah will hover in place near her, showing off his long tail plumes and his flying ability.

A lot of whydah species grow long tails. A lot of whydahs are also brood parasites, including this one, meaning that instead of building a nest and taking care of her own eggs, the female sneaks in and lays her eggs in the nest of a different species of bird. Then she flies away, probably whistling to make her seem extra nonchalant, and leaves the other bird to take care of her eggs and the babies when they hatch. She mostly lays her eggs in the nests of various species of finch, and not only do her eggs resemble the finch’s eggs except that they’re bigger, the babies resemble finch babies when they hatch, except they’re bigger.

Specifically, the babies have a really specific gape pattern. When an adult bird approaches its nest, a baby bird will gape its mouth wide to beg for food. This prompts the parent bird to shove some food down into that mouth. The more likely a baby is to be noticed by its parent, the more likely it is to get extra food, so natural selection favors babies with striking patterns and bright colors inside their mouths. Many finches, especially ones called waxbills, have a specific pattern of black and white dots in their mouths that pretty much acts as a food runway. Insert food here. The whydah’s mouth gape pattern mimics the waxbill’s almost exactly. But as I said, the whydah chick is bigger, which means it can push the finch babies out of the way and end up with more food.

The pin-tailed whydah is a common bird and easily tamed, so people sometimes keep it as a pet. This is a problem when it’s brought to places where it isn’t a native bird, because it sometimes escapes or is set free by its owners. If enough of the birds are released in one area, they can become invasive species. This has happened with the pin-tailed whydah in many parts of the world, including parts of Portugal, Singapore, Puerto Rico, and most recently southern California. Since they’re brood parasites, they can negatively impact a lot of other bird species in a very short time. But a study released in 2020 about the California population found that they mostly parasitize the nests of a bird called the scaly-breasted munia, a species of waxbill from southern Asia that’s been introduced to other places, including southern California, where it’s also an invasive species. So I guess it could be worse.

There are lots of other birds with long tails we could talk about, way too many to fit into one episode, but let’s finish with an extinct bird, since that seems to be the theme lately. In May 2020, an ancient bird was described as Kompsornis longicaudus, and it lived 120 million years ago in what is now China. Its name means long-tailed elegant bird. It was bigger than the other birds we’ve talked about today, a little over two feet long, or 70 cm, but a lot of that length was tail.

Kompsornis is only known from a single fossil, but that fossil is amazing. Not only is it almost a complete skeleton, it’s articulated, meaning it was preserved with all the body parts together as they were in life, instead of the bones being jumbled up. That means we know a lot about it, including the fact that unlike other birds of the time, it didn’t appear to have any teeth. It also shows other features seen in modern birds but not always found in ancient birds, including a pronounced keel, which is where wing muscles attach. That indicates it was probably a strong flier. It also had a really long tail, but unlike modern birds its tail was bony like a lizard’s tail although it was covered with feathers.

During their study of Kompsornis, the research team compared it to other birds in the order Jeholornithiformes, which seem to be its closest relations. There were six species known, with Kompsornis making a seventh—except that during the study, the team discovered that one species was a fake! Dalianraptor was also only known from one fossil, and that fossil was of a different bird with the arms of a flightless theropod added in place of its missing wings. Send that fossil to fossil jail!

You can find Strange Animals Podcast at strangeanimalspodcast.blubrry.net. That’s blueberry without any E’s. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. If you like the podcast and want to help us out, leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts or Podchaser, or just tell a friend. We also have a Patreon at patreon.com/strangeanimalspodcast if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!