Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 18:39 — 18.7MB)

Thanks to M Is for Awesome, who suggested the topic of domestication! This week we look mainly at foxes and how they relate to the domestication of dogs. Also, chickens.

Unlocked Patreon episode about chicken development and domestication: https://www.patreon.com/posts/21433845

A red fox:

Domestic foxes want pets and cuddles also coffee:

The fennec fox with toy I JUST DIED:

The raccoon dog is actually a species of fox:

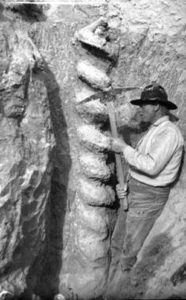

Show transcript:

Welcome to Strange Animals Podcast. I’m your host, Kate Shaw.

Back in episode 80, about mystery dogs and other canids, I said I was going to leave foxes for another episode. And here it is! But as I researched, it turned out that while there are lots of interesting foxes, they’re all pretty similar overall. So while we will learn about some of the more unusual foxes this week, I’m mostly going to talk about how animals are domesticated by humans. This is a suggestion from M Is for Awesome, who suggested domestication “and how it changes domesticated creatures from their wild cousins.” You may not know how this relates to foxes, in which case, I’m about to blow your mind.

But first, we should learn about how scientists think other canids became domesticated. You know, how dogs became dogs instead of wolves.

Domestication of wolves took place possibly as much as 40,000 years ago, but certainly at least 14,000 years ago. Gray wolves are the closest living relative of the domestic dog, but the gray wolf isn’t the dog’s ancestor. Another species of wolf lived throughout Europe and Asia, possibly two species, and domestication of these wolves occurred at least four different times in different places, according to DNA studies of ancient dog remains.

One of the oldest dog remains ever found dates to 33,000 years ago, found in a cave in Russia. Researchers think it wasn’t fully domesticated, but was probably connected with the people who had been using the cave as shelter. A 2017 study concluded that it isn’t related to any modern dogs and apparently was related to a species of wolf that has since gone extinct.

Many researchers think that wolves actually started the domestication process. Wolves hunt but they also scavenge, so they may have gotten into the habit of following bands of humans around to find scraps of food. Back in the hunter-gatherer days before we started growing crops, humans were nomadic, moving from place to place to find food. Wolves would have been attracted to the bones and other parts of dead animals humans left behind. If a wolf got too close to a campfire where humans were sitting around eating, two things might happen. If it was an aggressive wolf, the humans would chase it away or even kill it. But if it wasn’t aggressive, maybe because it was scared or young, a human might have tossed it a little bit of meat or a bone. That wolf would definitely hang around more, hoping for more food. If the humans grew used to it, it might even have started to consider itself part of the human’s pack. And if another predator approached, the wolf might growl at it and warn the humans, who would reward the wolf with more food. Over the generations, the wolves who got along best with humans would receive the most food and therefore be more likely to have babies that also got along with humans. It’s a lot easier to act as a camp guard and be given food and pets than it is to go out and try to kill ice age megafauna with your teeth.

Remains of a puppy dated to 14,000 years ago was found recently in a prehistoric grave in Germany. A test of its DNA indicates that it is related to modern dogs. The puppy was fully domesticated, well cared for, and had been buried with a man and a woman. Researchers can even tell that the puppy died of distemper, which leaves telltale marks on the teeth. The puppy had survived until the disease was well advanced, and it could only have done so with special care from humans. Even today distemper is a terrible disease among dogs. I had a puppy that died of it when I was little. Obviously, even 14,000 years ago dogs were already more than working animals or camp scavengers. Someone loved that puppy and tried to help it get better.

An interesting thing happens with domestication. Certain physical traits come along with the behavioral traits of reduced aggression and willingness to treat humans as surrogate parents. In the case of dogs, these often include a puppy-like appearance, including floppy ears, curled tail, smaller adult size, and a rounder head with smaller jaws. This isn’t the case with all dog breeds, of course, but the changes seem to be genetically linked to behavior. It’s called domestication syndrome.

So this is interesting, but how does it apply to foxes? Foxes are canids, but they aren’t all that closely related to dogs.

Well, in 1959 a Russian zoologist named Dmitry Belyaev decided to see if he could domesticate foxes. Taming and domestication are different things. A wild animal that has become used to certain humans can be considered tame, but a domesticated animal is one that is genetically predisposed to treat humans as caregivers. Belyaev didn’t just want to tame a few foxes, he wanted to try actually domesticating them.

He started his project by going to a fur farm that bred foxes to kill for their furs, which were then made into coats and other clothing. These were red foxes, which are common throughout much of the world, but because they were bred for their fur, they weren’t red. They were a darker color called silver, a color mutation, but other than that they were regular foxes. Belyaev chose foxes by how well they tolerated people, the ones that were less likely to bite.

He bred these foxes and when the babies grew up, he chose the least aggressive ones to breed. Then he chose the least aggressive babies from those parents, and so on. And after only six generations, he started to see results. Some of the foxes in the sixth generation actively sought out humans. They licked their hands, whined for attention, and even wagged their tails.

Something else happened too. The foxes started showing physical differences. Some had fur with white patches or various other color variations, some had floppy ears, some carried their tails so that the tip pointed up. All these traits are common in dogs, but pretty much never seen in wild foxes. Recent research shows that the changes are genetic and linked to lower adrenaline production. One color of fox, called Georgian white, has never been seen except in Belyaev’s domesticated foxes. It’s a lovely white all over with black ears and black or gray markings on the face and paws.

In case you’re wondering how much of the behavioral differences are due to increased human contact, the study also breeds the least tame foxes. They continue to look and act like wild foxes.

The breeding project has continued even though Belyaev died in 1985. These days almost all the foxes are as tame as dogs. Belyaev also conducted domestication projects with rats and American mink, both of which succeeded as well as the fox project. But if you want a pet fox, you’re out of luck. The foxes are occasionally for sale, but they’re extremely expensive and some parts of the world don’t allow foxes to be kept as pets at all, even these domesticated foxes. Occasionally someone will pop up online claiming to have some of the domesticated foxes for sale, but they always disappear after taking people’s money and never deliver any foxes.

Besides, even though Belyaev’s foxes are domesticated, they aren’t dogs. They don’t always behave in ways that make sense to humans. Humans and dogs have been buddies for untold thousands of years and we’ve basically evolved together, while foxes have only been domesticated for basically one human lifetime. One zoologist whose institute has several of the domesticated foxes for study and outreach says that she has to watch her coffee cup because if she doesn’t, one of the foxes might pee in her coffee. As soon as I read that, my desire to own a pet fox diminished. They’re really cute, but so are dogs, and while I have had a dog that would steal and eat sticks of butter off the counter, I never had to worry about him peeing in my coffee. Besides, the domestic foxes are also hard to house-train and still retain a wild fox’s musky odor.

The fennec fox is the smallest canid, and it’s sometimes kept as a pet, but it’s not domesticated. If the babies are taken from their mother very early, they grow up fairly tame, but they’re still wild animals and can be aggressive.

I have seen a fennec fox at the Helsinki Zoo! It was adorable. I definitely can see why people want one as a pet, but honestly, cats are about the same size and shape but are a lot less likely to bite. Also, cats purr. The fennec fox lives in northern Africa and parts of Asia and its fur is a pale sandy color with a black tip to the tail. Its eyes are dark and its ears are large. It stands only about 8 inches tall at the shoulder, or 20 cm, but its ears can be six inches long, or 15 cm. It eats rodents, birds and their eggs, insects, and other small animals, as well as fruit. It can jump really far, some four feet in one bound, or 120 cm. Because it lives in desert areas, it rarely needs to drink water. It gets most of its water through the food it eats, and researchers think it may also lap dew that gathers in the burrow where it spends the day.

The most common species of fox is the red fox. Foxes are canids related to dogs and wolves, and just to be confusing, male foxes are sometimes called dogs. Female foxes are vixens and baby foxes are cubs or kits. But the red fox isn’t the only species out there, not by a long shot.

For instance, the grey fox lives throughout North and Central America. It can look a lot like a red fox but its legs are always reddish or tan, unlike the red fox, which always has black legs. Instead of a white tip to its tail like red foxes have, the grey fox has a black tipped tail. It’s also not that closely related to the red fox or any other foxes, for that matter. Its pupils are rounded like a dog’s instead of slit like other foxes, which have eyes that resemble cats’ eyes.

The grey fox also has hooked claws that allow it to climb trees. That’s right. I said it can and does climb trees just like a cat. It’s nocturnal and omnivorous, which means it eats pretty much anything. It especially likes rabbits and rodents, but it also eats lots of fruit and insects.

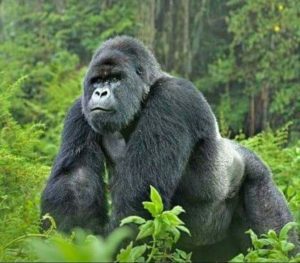

The only other canid that can climb trees is the raccoon dog, which is neither a raccoon nor a dog. It’s actually a type of fox, but it does look a lot like a raccoon at first glance. It has grizzled brown-gray fur, a black mask over the eyes and cheeks, and a short muzzle and rounded ears. And, of course, it also climbs trees like a raccoon. But it’s larger and bulkier than a raccoon with much longer legs, and its tail isn’t ringed like a raccoon’s tail.

The raccoon dog is native to parts of Asia, but it was introduced to parts of western Russia in the early 20th century as a fur animal and is now widespread throughout much of Europe. It’s an omnivore too; pretty much all foxes are omnivores. It eats rodents, frogs and toads, birds, fish, fruit and plant bulbs, some grains, and insects. You know, pretty much anything. It even eats toads that are toxic to other animals, diluting the toxins with massive amounts of saliva. And in cold areas, the raccoon dog hibernates. It’s the only canid that does.

Several months ago, I released a Patreon episode about chicken teeth that also talked about the domestication of chickens. It wasn’t my best episode but it’s relevant here so I went ahead and unlocked it for anyone to listen to. There’s a link in the show notes so you can click through and listen in your browser without needing a Patreon login or anything. Anyway, let’s finish up today with some information I just learned about the domestication of chickens. Specifically, a breeding project similar to the Belyaev foxes but with the wild birds that are the ancestors of domesticated chickens.

The bird is called the red jungle fowl, which lives in Asia and looks like a chicken, but is smaller than domesticated chickens. It was domesticated as long as 8,000 years ago but the wild bird still exists. A Swedish research team tried replicating Belyaev’s domesticated fox experiment with some of the wild birds. Like the foxes, the researchers bred a population of birds that were just ordinary wild jungle fowl and not selected for tameness, and a population of birds that were chosen because they tolerated humans a little more than usual. As each of the baby birds grew up, they were tested by having a human walk into the pen and try to touch it. The human wasn’t told whether the bird was from the tame group or the wild group. But after a couple of generations, it was obvious which was which. The tame birds became so tame that they didn’t mind the human at all.

And like the foxes, although the only trait the researchers selected for was tameness, the chickens began to change in other ways too. They became bigger and the hens laid more and larger eggs. This happened within only a few generations, which suggests that domestication is a much faster process than researchers once assumed.

And thanks to recent study, we’re pretty sure we know why these physical changes happen along with the behavioral changes. Selecting for tameness alters the genes that controls what are called the neural crest cells. When the embryo is developing, the neural crest cells migrate to different parts of the body. They affect the coat or feather coloring and some other physical developments, but they also affect the development of many other traits, including the fight-or-flight response. In other words, if you select for an animal that tends to be calm instead of fighty or flighty, you’re also accidentally selecting for differences in physical traits. Follow-up studies confirm that neural crest cells migrate differently in domestic animals than they do in their wild counterparts.

Research into domestication is a hot area of study right now, now that DNA and molecular genetics studies are more sophisticated. You know, in case anyone out there is considering a career in science.

You can find Strange Animals Podcast online at strangeanimalspodcast.com. We’re on Twitter at strangebeasties and have a facebook page at facebook.com/strangeanimalspodcast. If you have questions, comments, or suggestions for future episodes, email us at strangeanimalspodcast@gmail.com. We also have a Patreon if you’d like to support us that way.

Thanks for listening!